NJ Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages/

NJ Bilingual Educators

Welcome to NJTESOL/NJBE’s Annual Voices Journal. This publication is a representation of members’ thoughts on issues important to ESL, Bilingual, and Dual Language educators in New Jersey and the larger language teaching community. We are proud to have made changes in our publications this year so that our annual journal has a scholarly approach which reveals the deep commitment our writers and readers have for their teaching practice and students. NJTESOL/NJBE hopes you enjoy our first issue of NJTESOL/NJBE’s Annual Voices Journal and its companion, NJTESOL/NJBE’s Weekly Voices.

Annual Voices Journal is the official publication of NJTESOL/NJBE, issued annually each winter. Articles in the NJTESOL/NJBE Voices Journal include current issues, classroom explorations, program description/exemplary scheduling, and alternative perspectives as related to the teaching of English to speakers of other languages, Bilingual Education, and Dual language programs including students who are U.S.-born bilinguals, “generation 1.5”, immigrants, and international students. Articles may focus on any educational level, from kindergarten to university, as well as on adult school and workplace literacy settings.

ARTICLES:

Designing Assessments to Facilitate Oral Language Development

Margaret Churchill, Kevin Calixto, and Maria Cecilia Vila Chave

WIDA’s Key Language Uses target specific language features; the discussed assessments focus on communicative construction across the four domains to evaluate explicit academic purposes and linguistic patterns needed to build language proficiency in English.

Kristen Vargas and Tasha Austin

The interaction of the experience of a pre-service teacher of color with the dominant narrative in teacher education and the use of a critical lens to evaluate the outcome.

Hana Prashker, Patricia George, and Elizabeth Franks

A discussion on steps and interventions to support ELLs through high school graduation into enrollment and success at college.

Pedro Trivella

Educating for global competence increases students’ classroom engagement and future success through planning which includes a cultural lens and critical thinking.

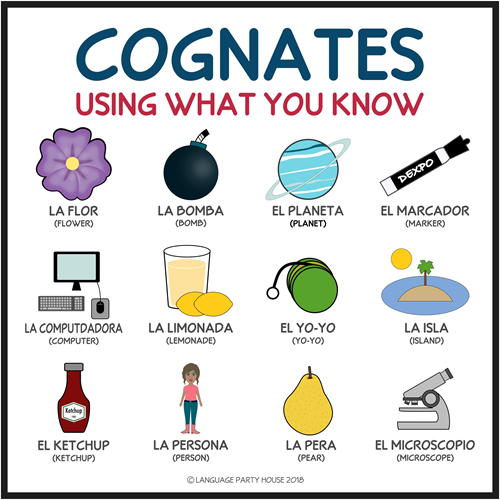

Amanda Guarino and Angello Villarreal

Views on using cognates and translations for students with and without a solid academic foundation in their native language, bridging content connections between their native language and English.

Photo: Sunrise at the Jersey Shore, taken by JoAnne Negrin, Vineland Public Schools, NJTESOL/NJBE President, 2016-2018

Designing Assessments to Facilitate Oral Language Development

By Margaret Churchill, Kevin Calixto, and Maria Cecilia Vila Chave

Margaret Churchill teaches at William Paterson University and Closter Public Schools, New Jersey

Kevin Calixto teaches in the Clifton Public Schools, Clifton, New Jersey

Maria Cecilia Vila Chave teaches in the Morris School District, Morristown, New Jersey

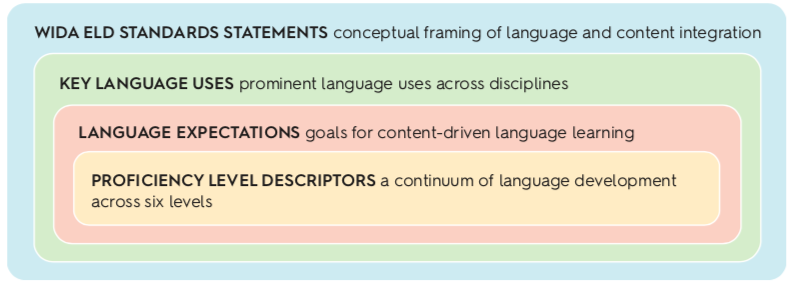

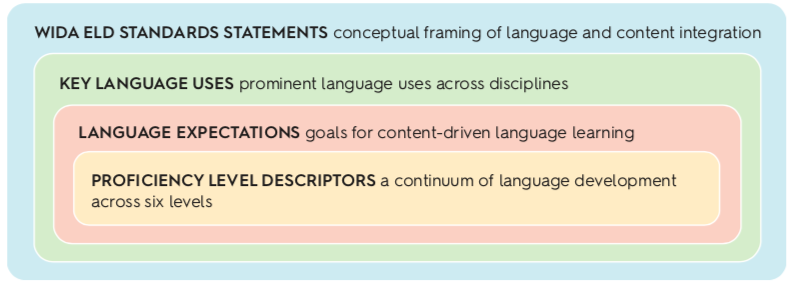

WIDA’s Key Language Uses feature prominently in the 2020 release of the WIDA ELD Standards Framework (WIDA, 2020).

Figure 1: WIDA ELD Standards Framework

The Key Language Uses help bring to the forefront specific language features that make explicit the academic purposes and linguistic patterns needed to build language proficiency in English. The emphasis is on the communicative purposes of language; that is, constructing ways that students can engage with academic language across the four domains: Listening, speaking, reading, and writing (Shafer Willner, Gottlieb, Kray, et al., 2020).

The Big Ideas of the WIDA English Language Development (ELD) Standards Framework (found in Section 1 of the document) make clear that the intent of this updated organization of standards is to include “the integration of language and content, which is critical in the planning and delivery of instruction” (Shafer Willner, Gottlieb, Kray, et al., 2020. Assessment plays a critical role in determining the annual progress of multilingual learners, and is required in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA, 2015). By integrating language and content in classroom assessment design, teachers can build multilingual learner success towards meeting required annual progress.

This article shares a classroom-based assessment template that showcases the Key Language Uses. Rooted in the WIDA Guiding Principles of Language Development (2019), it provides teacher-practitioners with a model to follow as they plan for instruction and assessment under a new framework. It contains an overview of how the WIDA Key Language Uses were used to lay the groundwork for an oral language assessment design that utilizes one Key Language Use, Explain, a tour of the Key Language Use Assessment Template, and sample assessments from teacher practitioners.

PART 1: What are the Key Language Uses?

The Key Language Uses identify four prominent language uses across academic content standards in ELA/literacy, mathematics, science and social studies: Narrate, inform, explain, and argue. Table 1 below provides the definitions used in the 2020 WIDA ELD Standards Framework document.

Table 1. Definitions of the Four Key Language Uses

Each purpose encompasses an inherent structure, along with language functions and features typified within, that must be taught in tandem with required content. These four Key Language Uses appear across academic disciplines and in all modalities: oral, written, and visual. The 2020 WIDA ELD Standards Framework provides guidance to help educators deconstruct the Key Language Uses and their components. For example, within the framework, samples are provided, with an emphasis on building cohesion in student language production. For multilingual learners to achieve success within each Key Language Use, teachers will need to design assessments that provide simultaneous structure for both language and content in performance tasks that target a Key Language Use.

Educators can directly participate in this construction through the Key Language Use Assessment Template shown in Table 2. Teacher-practitioners can use this template to design oral language assessments for the Key Language Use shown here: Explain. These assessments could be for existing units, or easily implemented for a single text source. We will share exemplars of oral language assessments around the Key Language Use of Explain for multilingual learners.

Designing Assessments and the other articles continue below.

How is Explain Used in Science?

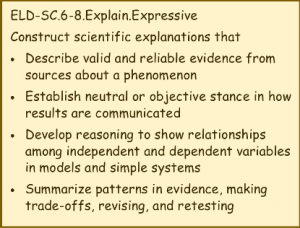

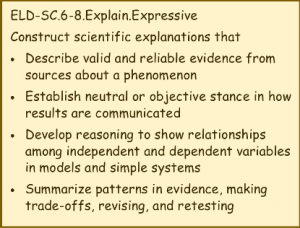

Figure 2: Language Expectations – Expressive, Grades 6-8

Scientific explanation asks students to give an account of how or why something happens- an eclipse, the metamorphosis of an animal, or how water moves through a cycle. The emphasis is on explaining how or why a phenomenon occurs, typically in steps or stages, with connective (think: transition) words told in the timeless present tense. Explanations may be cyclical, (the nitrogen cycle), causal (why tides occur), sequential (or linear, how to sprout beans), systemic (how body systems function), factorial (factors that lead to global warming), and consequential (how the pandemic affected air quality in cities) (Derewianka & Jones, 2016).

Design Features of the Key Language Use Assessment

The Key Language Use Assessment Template (see Table 2) makes explicit both the steps in the design process and the language requirements specific to each language use. Regardless of the academic content, or Key Language Uses, the assessment must balance the language patterns of the genre family with the linguistic features of the text (see Figure 2). Linguistic features might include use of technical vocabulary, connective words, sentence types, grammatical construction, and discourse structure of an explanation. To make the process achievable for students, teacher-made materials that clarify these patterns and features are embedded in the assessment design.

As shown below in Table 2, the Key Language Use Assessment Template is organized in a table that outlines the design elements of the assessment in the left column, with the content requirements, materials, and linguistic resources in the right column.

In Table 2, yellow highlighting is used to show replaceable features, thus creating a template for teacher-created assessments in any grade or content area. To the extent possible, digital links were provided to make this assessment possible in fully virtual settings. The template models both the steps in the process and classroom examples at each stage. Once the initial grade level, unit, and lesson are chosen, the Key Language Use can be identified.

Table 2. Key Language Use Oral Assessment Design Template

| Design Elements |

Content, Materials, Resources |

| Grade level |

NAME THE CONTENT AREA: math, science, social studies, health, etc. |

| Curricular Unit Topic |

Understanding the Natural World |

| Essential Question |

How does water move in a cycle? |

| Key Language Use |

Explain a cyclical process |

| Text/Source |

Pearson Keystone: Building Bridges textbook, 2013 |

| Other possibilities: Reading A-Z, Scholastic magazine articles, read aloud books |

| Illustration/Diagram/Infographic |

PROVIDE SOURCE LINK & THUMBNAIL (see below) |

| https://sciencealtavista.files.wordpress.com/2010/02/water-cycle.jpg |

| Discipline-Specific Technical Language |

LIST HERE: |

| Water cycle, state (of matter), evaporation, condensation, precipitation, collection, clouds, vapor, droplets |

| Language Features Focus |

Present tense verbs mini-lesson |

| List of Transition Words [Connectives] |

Procedural steps https://www.k12reader.com/transition-words/transition_words_of_time_sequence.pdf |

| PROVIDE SOURCE LINK |

| Anchor Chart/Digital Resources |

See below – MAKE ONE |

| Can be handwritten or digital |

| Cue Cards |

Structure words + vocabulary + transition words |

| MAKE ONE SET |

| Sentence Frames/Script |

CHOOSE ONE (see below) |

| Rehearsal |

Partner practice with image and cue cards. Teacher provides constructive feedback. Do multiple attempts. |

| Recording |

Garageband on laptop station. Classmate assists with cue cards during recording. Student looks at the image while speaking. |

| How will you record it? What are your options? |

| Self-Assessment |

How will students review their oral responses? What will they use? How will you facilitate this? Write 4-5 sentences. |

| Rubric for evaluation |

WIDA Speaking Rubric AND/OR WIDA 2020 Proficiency Level Descriptors |

Table 2 serves as a sample template for a scientific explanation of the water cycle. Explaining how water moves through a cycle requires application of knowledge from the three states of matter, since it includes the phenomenon that water must change its state in order to move through the cycle.

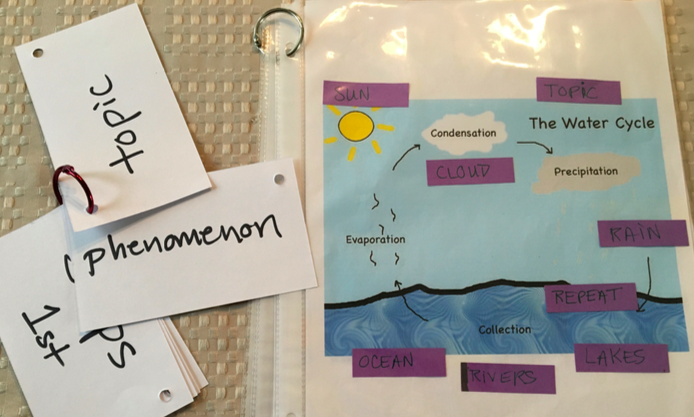

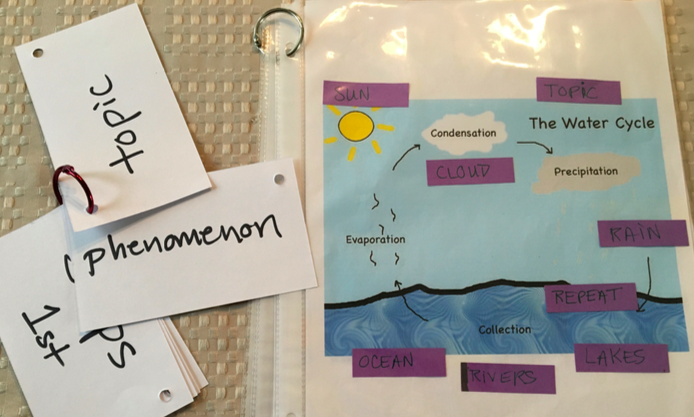

Figure 3: Teacher-made materials- cue cards and labelled diagram

Students’ understanding of the phenomenon developed from the selected text listed in Table 2, the visual provided (Figure 3), and through the use of a teacher-made discovery table with samples of the three physical states of water. At the discovery table, a guided class discussion helped establish key vocabulary and students’ prior knowledge about water and its forms- ice, liquid water, and steam. The correlation to the water cycle was discovered through teacher questioning and student explanation about how water changes between these forms based on temperature. The labelled diagram, The Water Cycle (Figure 3) was deconstructed together as a class, with students labelling the nouns in the diagram to assist in the explanation and use it later during recorded performance.

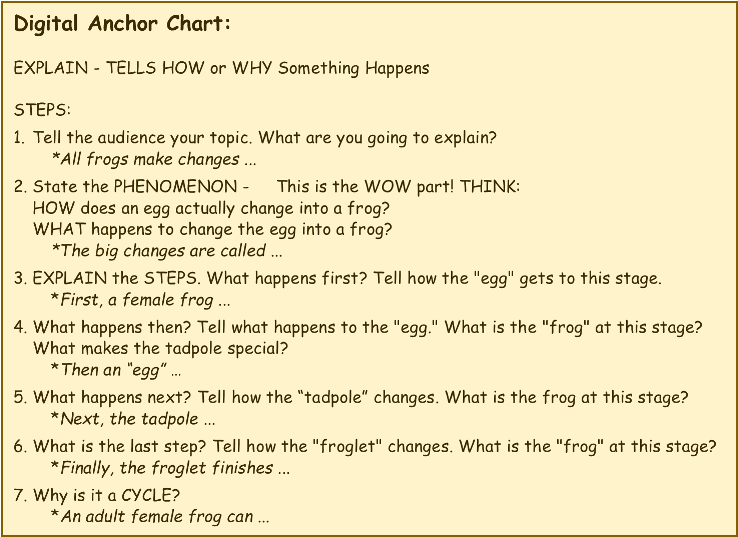

Because academic vocabulary, language focus, and connective words help facilitate language usage, these elements are incorporated in teacher-made materials (Figure 3) used during the assessment: A teacher-made anchor chart, sentences frames (or a script), and cue cards (with steps and connective words). After the diagram is examined and labelled with required vocabulary, a teacher-made anchor chart is presented as a reference document to articulate the flow of information required in an explanation. The purpose of the anchor chart (see Figures 5 and 6) is to model for students how they will synthesize their response by pulling together the required content, vocabulary, and linguistic features to formulate a cohesive explanation.

To prepare for performance, students practice with peers and act as direct supporters to each other by assisting with cue cards (see Figure 3). They also listen for content vocabulary terms and key noun phrases. They take turns as supportive peer coaches before the recorded performance. Because speaking is recorded on the annual ACCESS for ELLs 2.0 assessment, it is critical that students build practical experience in answering oral prompts with visuals and voice recording. Additionally, beginning level students benefit from the use of a script for practice, to help scaffold the expected response and provide a measure of success.

A self-assessment is completed post-recording, to build students’ metalinguistic awareness in analyzing their own language production. The self-assessment should require accountability in both the content and language elements of the assessment design. Recordings can be transcribed, so that students can see what was actually said and use it to complete their self assessment, along with these guiding questions:

- Did the student use target vocabulary?

- Did they state the phenomenon?

- Was each step introduced and named?

- Were details provided for each step?

- How did the explanation end?

For current student assessment purposes (as the multi-year transition from the 2012 WIDA ELD Standards to the 2020 WIDA ELD Standards Framework begins), the WIDA Speaking Interpretive Rubric K-12 (WIDA, 2014) for classroom use can be utilized. The rubric provides guidelines for analyzing oral language’s linguistic complexity, language forms, and vocabulary usage. The expected characterizations are generalized by proficiency level, providing an overall assessment of oral language performance.

To align with the 2020 WIDA ELD Standards Framework, teachers can assess student performance by applying the appropriate grade-level cluster WIDA Proficiency Level Descriptors for Expressive Communication (see Table 3). One of the advantages of the new WIDA Proficiency Level Descriptors is that they provide more specific criteria for discourse analysis of sentence and text-construction, which specifically focuses on the flow of information expected in an explanation.

Table 3. Excerpt from Grades 6-8 WIDA Proficiency Level Descriptors for the Expressive Communication Mode (Speaking, Writing, and Representing)

Toward the end of each proficiency level, when scaffolded appropriately, multilingual learners will…

| Criteria |

DISCOURSE |

Organization of language |

| End of Level 1 |

Create coherent texts (spoken, written, multimodal) using… |

sentences that convey intended purpose with emerging organization (topic sentence, supporting details) |

| End of Level 2 |

short text that conveys intended purpose using predictable organization (signaled with some paragraph openers: First…Finally, In 1842, This is how volcanos form) |

| End of Level 3 |

expanding text that conveys intended purpose using generic (not genre-specific) organizational patterns (introduction, body, conclusion) |

| End of Level 4 |

text that conveys intended purpose using genre-specific organizational patterns (statement of position, arguments, call to action) with a variety of paragraph openers |

| End of Level 5 |

text that conveys intended purpose using genre-specific organizational patterns with strategic ways of signaling relationships between paragraphs and throughout text (the first reason, the second reason, the evidence…) |

| Level 6 |

text that conveys intended purpose using genre-specific organizational patterns with a wide range of ways to signal relationships throughout the text |

Ultimately, this template has potential for classroom application in all grades and disciplines. It makes an easy addition to existing units where we ask students to explain phenomenon. It provides teachers with a way to bridge the new expectations for language and student performance in the 2020 WIDA ELD Standards Framework. Most importantly, it allows all students to reach individual proficiency level expectations with scaffolded support throughout all aspects of the assessment.

PART II: Examples of Assessment in Practice

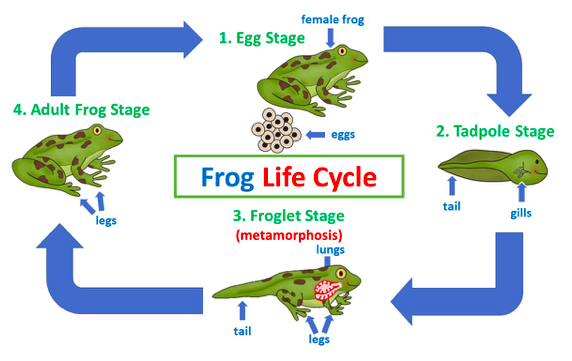

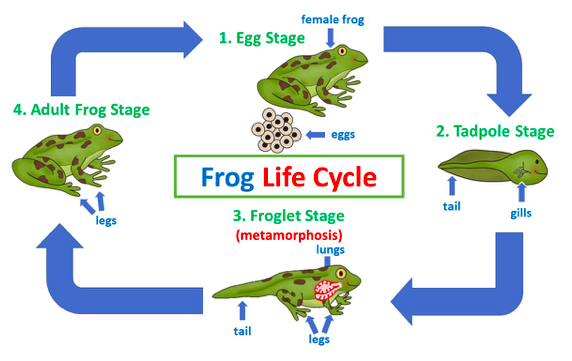

Figure 4: Frog Life Cycle Infographic

The teacher-practitioner [Kevin Calixto] applied the Key Language Use Assessment Template, created by Margaret Churchill as part of the course work for ESL Content Instruction and Assessment at William Paterson University. The frog life cycle Key Language Use Oral Assessment assesses student explanations related to the changes frogs exhibit during their life cycles.

The exemplar shown in Table 3 was designed to be utilized with ESL second grade students, as its academic science content is based on the second grade Houghton Mifflin Harcourt textbook: Science Fusion. The infographic (see Figure 4) can be examined within mini lessons to introduce and teach students academic science vocabulary and content regarding the changes frogs exhibit during their life cycles. Students also use the infographic during their own oral explanation.

Students have the opportunity to develop English language use and awareness during language production by focusing on the present tense subject-verb agreement and the use of transition words. Two sets of cue cards were created, a structure and transition words set and a vocabulary words cue card set, which act as prompts during practice. All links on the template below lead to a material designed for use during this assessment.

Table 4. Key Language Use Oral Assessment on Frog Life Cycle

| Grade level |

2nd Grade ESL Language Arts and Science Content |

| Curricular Unit Topic |

All About Animals |

| Essential Question |

How does a frog change during its life cycle? |

| Key Language Use |

Explain a frog’s life cycle process. |

| Text/source |

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Science Fusion Grade 2 Textbook, 2012 (Pages 108-109) |

| “Frog” by Wendy Perkins (obtained from the online educational website: getepic.com) |

| Illustration/diagram/infographic |

Link to frog life cycle infographic |

| Academic vocabulary |

life cycle, metamorphosis, egg, hatches, tadpole, gills, tail, grows, legs, froglet, lungs, frog |

| Language focus |

Present tense verbs mini-lesson (focus on subject-verb agreement). |

| Transition word list |

Link for transition word lists for “Beginning,” “Middle,” and “End” |

| Link for description of transition words and lists of transition words utilized to “Show Order” |

| Anchor chart/digital |

Anchor Chart (see below). |

| Cue cards |

Structure words + vocabulary words + transition words cue card set (see below). Website for cue card sets |

| Sentence frames/script |

Script |

| Rehearsal |

Partner practice with image and cue cards. Teacher provides constructive feedback. Do multiple attempts. |

| Recording |

Students’ audio will be recorded |

| Classmate(s) will assist with cue cards during practice. |

| Teacher will assist with cue cards during recording. |

| Students will look at cue cards and infographic while speaking. |

| Self-assessment |

Transcribe students’ oral responses and use a matching checklist to individually review with each student if all required components. Possible areas of improvement will be discussed. |

| Rubric for evaluation |

WIDA Speaking Rubric |

This template guides teachers through mini-lessons, focusing on academic science content and vocabulary, and linguistic features, regarding present tense subject verb agreement and the use of connective, or transitional words.

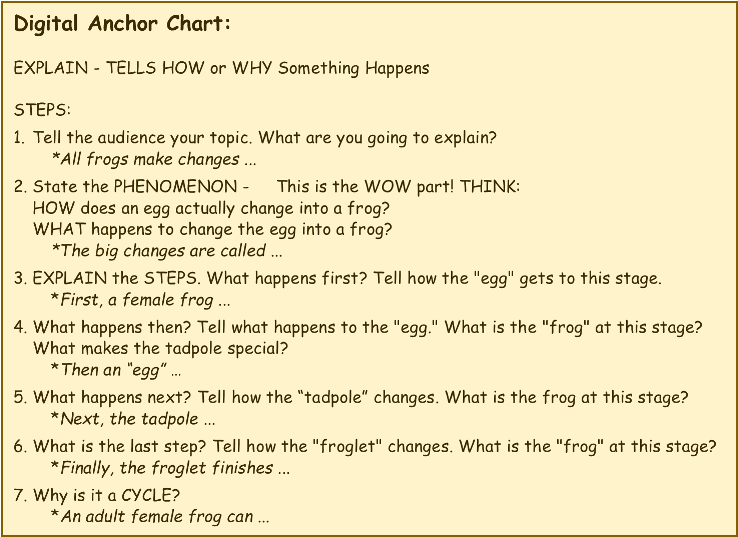

The anchor chart (see Figure 5) introduces students to the oral assessment task and serves as a model, to guide students through the construction of the explanation while practicing the oral assessment task. Partners then practice orally, explaining the changes frogs exhibit during their life cycles.

Figure 5: Anchor chart for Frog Life Cycle Explanation

The Key Language Use Oral Assessment Template is designed to accommodate students with a variety of English language proficiency levels: a script is created, which can be modified according to student needs and utilized with beginners or newcomers. As students practice their oral explanations with partners, the teacher provides constructive feedback. Once students have been allotted sufficient practice time, the teacher audio records oral explanations as each student is prompted with cue cards while referencing the infographic (Figure 4). Finally, the teacher transcribes and guides student analysis of oral response transcripts, which are analyzed during self-assessment to identify strengths and areas for improvement in future assessments.

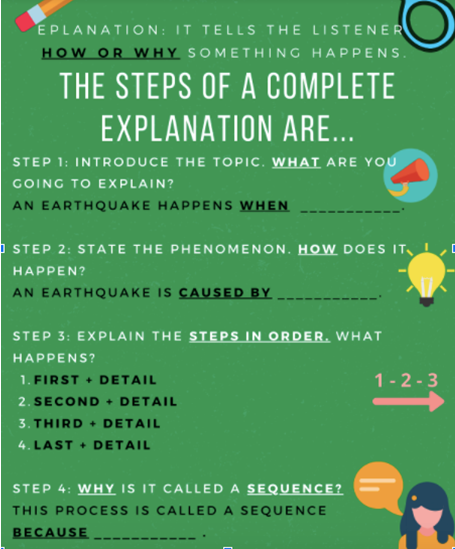

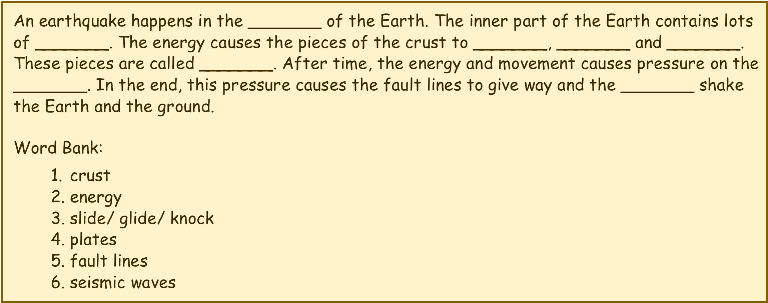

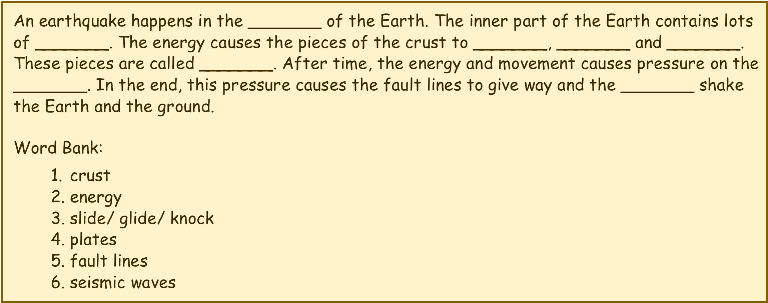

As previously mentioned, explanation also includes causal phenomenon, which follows a timed sequence, and contains its own innate language features (Derewianka & Jones, 2006). The goal of the Key Language Use Assessment on Earthquakes (Table 5) was to enable students to use the academic and content vocabulary while empowering them to participate in academic conversations. Causal explanation requires students to demonstrate understanding of how a phenomenon occurs, which, in the case of earthquakes, produces certain effects. The oral assessment allows for a check for understanding of the content through language, at a range of English language proficiency levels. The design process of this oral assessment is divided into three focus areas. First, it includes various forms of content and language input: a text, an infographic, a predetermined academic vocabulary list, and a language focus. Second, it provides multiple scaffolds to enable student success: an anchor chart, cue cards, sentences frames, and a script. Lastly, it models an instructional plan that aligns and culminates with the assessment itself: rehearsal, recording, and self-assessment.

Table 5. Key Language Use Assessment on Earthquakes

| Grade level |

4th grade ESL LA and science content |

| Curricular Unit Topic |

Earth’s Systems: Processes that Shape the Earth |

| Essential Question |

How does an Earthquake happen? |

| Key Language Use |

Explain a causal phenomenon |

| Text/source |

Steps of Earthquake formation |

| Illustration/diagram/infographic |

“Steps of Earthquake Formation” Diagram |

| Academic vocabulary |

Crust, Energy, Slide, Glide, Knock, Plates, Fault lines, Seismic Waves |

| Language focus |

Present tense verbs mini-lesson |

| Transition word list |

Explain steps in a sequence – Transitional Words |

| Anchor chart/digital |

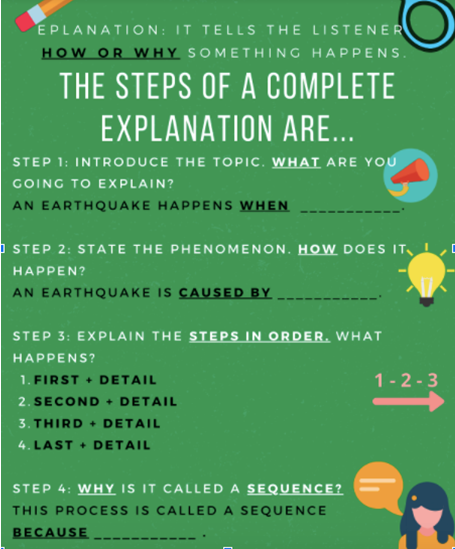

The steps of a complete explanation (See below for digital anchor chart) |

| Cue cards |

Structure words + vocabulary + transition words |

| Sentence frames/script |

Script (see below) |

| Rehearsal |

Partner practice with image and cue cards. Teacher provides constructive feedback. Do multiple attempts. |

| Recording |

Voice Recorder Classmate assists with cue cards during recording. Student looks at the image while speaking. |

| Students will record using their Chromebooks during their “Speaking Center” (ESL rotation/ center model). They will use their headphones with a microphone. |

| Self-assessment |

- The teacher will transcribe the recording and ask students to check their work (highlight/ circle) if they have all the required steps with a checklist.

- Success, 1 Need to improve and 1 Goal.

|

| Rubric for evaluation |

WIDA Speaking Rubric |

Figure 6: Anchor Chart for Explanation

The inclusion and balance of these three focus areas allow the assessment to be used for multiple proficiencies and learning modalities (auditory, visual, kinesthetic, and interactional) present in a classroom. Students view, listen, discuss and use manipulatives throughout the process.

The anchor chart (see Figure 6) on the key language use of explain not only defines what the concept is, but provides a methodological approach to an explanation by giving four steps that must always be included. This assessment design shows an integrated approach to academic content and language to promote oral language development towards proficiency.

The anchor chart (Figure 6) utilizes multiple scaffolds such as sentence frames, visuals, and bolding of keywords to be accessible to all learners. With the same goal in mind, the script (see Figure 7) and cue cards provide a supportive framework for the students to demonstrate content mastery through targeted language construction.

Figure 7: Script for Newcomers

As educators work together to examine the 2020 WIDA English Language Development Standards Framework, student performance needs to be at the forefront. The WIDA Key Language Uses are the cornerstone of this new framework. Instruction of multilingual learners will require a significant shift in the near future, with greater demands placed on the implementation of the WIDA Key Language Uses. We believe that tools like the Key Language Use Oral Assessment Template can develop students’ oral language proficiency in English while building success in scientific explanations, a task often featured in the ACCESS for ELLs 2.0 assessment.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Dr. Lynn Shafer Willner, WIDA researcher and lead writer of the WIDA 2020 English Language Development (ELD) Standards Framework, for her guidance and feedback during the writing of this article.

References

De Oliveira, L. C., Jones, L., & Smith, S. L. (2020). Interactional scaffolding in a first-grade classroom through the teaching–learning cycle. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism.

Derewianka, B., & Jones, P. (2016). Teaching language in context. Victoria, AU: Oxford Press.

Gottlieb, M. (2016). Assessing English language learners: Bridges to educational equity: Connecting academic language proficiency to student achievement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, A SAGE Company.

Lundgren, C., & D’Costa, S. (2019). Using Language Pathways to Foster Language Awareness and Educational Equity. MinneTESOL, 35(1).

Rose, D., & Martin, J. (2012). Learning to write, reading to learn. South Yorkshire, UK: Equinox.

Shafer Willner, L., Gottlieb, M., Kray, F.M., Westerlund, R., Lundgren, C., Besser, S., Warren, E., Cammilleri, A., & Cranley, M.E.(2020) .Appendix F: Theoretical foundations of the WIDA English language development standards framework, 2020 edition. In WIDA English Language Development Standards Framework, 2020 Edition. Wisconsin Center for Education Research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. (pp. 354-374).

WIDA. (2020). WIDA English Language Development Standards Framework, 2020 Edition: Kindergarten-Grade 12. Wisconsin Center for Education Research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. https://wida.wisc.edu/teach/standards/eld

WIDA. (2019). WIDA Guiding Principles of Language Development. Wisconsin Center for Education Research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/Guiding-Principles-of-Language-Development.pdf

WIDA. (2014) WIDA Speaking Interpretive Rubric for K-12. Wisconsin Center for Education Research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/WIDA-Speaking-Rubric-Gr-1-12.pdf

Cultivating Joy: An Introspective on Developing ESL Practitioners of Color

By Kristen Vargas and Tasha Austin

Kristen Vargas has a Bachelors in Linguistics and Masters in Language Education and writes for the Rutgers Humanist. Tasha Austin is a lecturer in Language Education at the Rutgers Graduate School of Education and the Teacher Education Special Interest Group Representative for NJTESOL-NJBE.

Introduction and Framework

After a semester of student teaching, I found myself reflecting on my experiences in the classroom as a student of color and questioning how those helped shape my beliefs about language, or linguistic ideologies, and how I chose to execute instruction -my teaching praxis. It drove me to compare the process of navigating the academic and professional institutions of becoming an educator to drowning, and doing so within the context of COVID-19 felt like:

Figure 1. Untitled comic of hand waving from under water (Source: Gudim, 2017)

Figure 1. Untitled comic of hand waving from under water (Source: Gudim, 2017)

As a means of naming my reality (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995) I share my counterstory with the hope that my voice might break through the dominant narrative in teacher education which does not center the experiences of pre-service teachers (PST) of color due to their severe underrepresentation in U.S. K-12 public schools (National Center for Education Statistics, 2018). Despite the long standing cultural mismatch of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) teachers within US classrooms, upon my completion of a teacher preparation program, I decided not to enter K-12 teaching. I strategically use the term BIPOC to represent how across the spectrum, specific communities are racialized and feel the impact of structural racism. In an effort to better understand what facilitated this personal choice, I looked through the lens of critical consciousness (Freire, 1996) in search of the joy I experienced in my training. Freire explains critical consciousness as the ability to deconstruct the power structure of the dominant group in order to envision something better and construct something new. To facilitate this critical reflection, I decided to engage in an introspective grounded by the following three questions:

- What is my first memory of being in a classroom?

- Have I ever felt the need/urge to perform resistance in a classroom?

- When has learning been a process of joy for me?

Literature & Analysis

I reflected on my graduate coursework, focusing on my experiences in student teaching and capstone presentation. I kept returning to something my advisor asked us to do throughout our final semester: find the joy. As I was completing my Master of Education two months into the COVID-19 pandemic, I admittedly felt intense resistance to this mission.

My concern for students and educators from minoritized and low-income communities increased tenfold when the first wave of the pandemic hit. The communities hit hardest by COVID-19 were also the communities that most depend on schools as protective factors (Center for Disease Control, 2020); thus, according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, school closures exacerbated already significant economic and racial disparities (NAACP, 2020). I was no exception to this racialized impact and needed to use a critical lens to reflect on my personal experiences as affected by structural racism, and how I myself was experiencing school as a PST.

What is my first memory of being in a classroom?

I focused on my own educational history and formative experiences. My first memory of being in a classroom was of being one of 24 first graders with a white teacher who yelled at us all day. The internalization of linguistic ideologies which posit that minoritized languages — and therefore, minoritized people— are inferior to White Mainstream English and its speakers, can lead to students losing “confidence in the learning process, their own abilities, their educators, and school in general” (Charity Hudley & Mallinson, 2014, p. 33, as cited by Baker-Bell, 2020, p. 27). Whether someone’s first memories are positive or negative shapes how they walk into spaces of learning and how they have learned to be within those spaces. What students of color learn about how they are perceived through the lens of whiteness is often internalized (Baker-Bell, 2020). Although I’ve had many other contributing experiences to my identity as a learner, the first one is deeply rooted in my experience of race, power, and control.

Deconstructing my first memory of being in a classroom as a student revealed a correlation I made between whiteness and power in contrast to non-whiteness and suppression.

Have I ever felt the need/urge to perform resistance in a classroom?

The second question focuses on agency and advocacy. In my reflection I discovered that my resistance to centering the joy of teaching was not due to the absence of that joy rather, it was a response to the “hokey” hope that “ignores the laundry list of inequities that impact the lives of urban youth” (Duncan-Andrade, 2009, p. 182). The joy I was being asked to pursue as an educator was akin to the hokey hope that BIPOC students face every day in the classroom. What I felt to be inauthentic or uncritical caring deepened my loss of confidence in my program, my educators, and my own efficacy as an educator (Duncan-Andrade, 2009, p. 183). My resistance was rooted in this loss of confidence and rarely manifested in any visible action. The deconstruction of my resistance in the face of an expectation to “find joy” led me to believe that the need to resist does not always lead to visible or physical resistance. Still, what was not physically displayed took up residence in my body emotionally causing me to distance myself from the profession to which I was initially drawn.

When has learning been a process of joy for me?

Through my academic and professional development, I frequently sensed the dissonance between the preparation I was receiving as a PST, and how I was actually being educated. It felt like the insistence on finding the joy in the middle of a pandemic and racial reckoning ignored the collective, personal, and professional grief that COVID-19 had provoked. In the communities to which I belong, school closures brought forth discussions about food inequity, child-care access, technology access, and countless other supports that schools provide to their students and families (NAACP, 2020). According to Consumer News and Business Channel, school closures also brought forth professional concerns about teacher shortages, digital dexterity, financial compensation, in addition to the personal health concerns the pandemic exacerbated (CNBC, 2020). With only two months remaining in my teacher preparation program, it was within the context of these discussions that I began feeling a real professional community. When the first wave of the pandemic hit, suddenly, all of our discussions about inequity were taken out of the theoretical and into our actual preparation. We began interrogating how our experiences as students were impacted by the shift to remote learning and how this would inform our praxis and our priorities as new teachers in a completely unfamiliar learning environment. Finally, unpacking the realities of grief with people who were talking about the systemic inequities present in schools and how these affect not only students and families, but teachers as well, gave me access to a true and critical joy.

Conclusion & Recommendations

The memory of being policed in a learning space transforms the classroom into a space of harmful suppression. Such memories are painful, but also should be drawn upon as a valuable lived experience which informs how I approach teaching. Without this grounding, centering the joy of teaching felt like erasing my experience of grief and reinforced the idea that suppression of that grief was and is critical to my success as an educator. This unfortunately informed my decision to not enter the teaching profession despite my potential impact.

The pursuit of joy that is responsive to grief led me to conceptualize critical joy. Critical joy is the acknowledgment and reflection of grief, and I suspect that is the type of joy PSTs of color yearn for when considering entering the teaching profession, particularly in the discipline of language education. Understanding how your memories of studentship inform your resistance in spaces of learning allows you to begin pursuing, creating, and building the critical joy that benefits students, teachers and the field in general. Educators must understand the power they hold in the classroom and how the language they use serves to maintain that power, for better or for worse.

References

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy. Routledge.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, September 15). SARS-CoV-2–Associated Deaths Among Persons Aged 21 Years – United States, February 12–July 31, 2020.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6937e4.htm?s_cid=mm6937e4_w.

Duncan-Andrade, Jeffrey. (2009). Note to Educators: Hope Required When Growing Roses in Concrete. Harvard Educational Review. 79.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (revised). New York: Continuum.

Gudim, A. [@gudim_public]. (2017, June 19). Untitled comic of hand waving from under water [Graphic]. Instagram.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BViCi_bFmkQ/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Hess, A. J. (2020, December 14). 27% of teachers are considering quitting because of Covid, survey finds. Retrieved from

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/14/27percent-of-teachers-are-considering-quitting-because-of-covid-survey.html

Ladson-Billings, G., & Tate, I. V. WF (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education, 47-68.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). (2020, April 1). Coronavirus Impact on Students and Education Systems. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2020, May). Characteristics of Public School Teachers. Retrieved January, 13, 2021.

Current and Former English Language Learners (ELLs): Supporting the Transition from Secondary Schools to College

By Hana Prashker, Patricia George, and Elizabeth Franks

Hana Prashker, the NJTESOL/NJBE ESL Secondary Representative, teachers at the Hasbrouck Heights Public Schools. Patricia George, the NJTESOL/NJBE Higher Education Representative, teaches at TCNJ. Elizabeth Franks is the NJTESOL/NJBE Socio-Political Representative

According to Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce (2019), two-thirds of all jobs will require postsecondary education now and in the future. Some ELLs lag behind non-ELLs in terms of college access and completion, with roughly one in eight ELLs completing a college degree within six years compared with one in three non-ELLs (George, 2019). Due to the need for further instruction in writing and grammar, former ELLs take remedial ESL classes and often do not advance to credit-bearing English classes (Bailey, Jeong, & Cho, 2010). This discrepancy is demonstrated most frequently with the high numbers of ELLs, former ELLs, and Generation 1.5 students who need to take ESL or Basic Skills classes before taking credit-bearing classes.

New Jersey’s High School English Language Learners

The state of New Jersey has the fourth-highest number of recent immigrant students in the United States (George, 2019). As reported by the New Jersey Department of Education (2019), there are approximately 90,000 ELLs in our public schools. High School ELLs fall into four general groups:

- Learners with limited formal school in their home countries, also referred to as students with a limited or interrupted formal education (SIFEs / SLIFEs).

- Learners with grade-level, primary-language literacy, who are developing literacy in English, also referred to as current ELLs.

- Learners with inconsistent school histories, with limited development in either the primary language and/or English, sometimes referred to as Generation 1.5. Generation 1.5 learners are familiar with both the U.S. educational system and American culture. These learners have typically developed social and oral language skills in English while speaking or understanding another language at home. Although Generation 1.5 learners vary significantly in their first language skills, they may have low proficiency in academic English required for success in post-secondary education (NJTESOL/NJBE, 2008).

- Many former ELLs still need to take ESL or remedial Basic Skills classes in college to improve grammatical, reading and writing skills before beginning college credit-bearing classes.

Secondary and college ESL educators have discussed the challenges that students face in the transition from high school to college. This paper recommends actions that various stakeholders at both levels can implement in order to support current and former ELLs.

The Students

Efforts must be made to impress upon the students themselves the importance of student agency. Strategies that teach students to advocate for themselves should be part of the curriculum. Participating in extracurricular activities is another way to build relationships and expand opportunities to use English which is invaluable. Partnering with the local library, these learners can take advantage of free English educational and informational apps and explore the available resources. Working part-time (not full-time) can also contribute to developing time management, demonstrating responsibility, and gaining life experiences. There is a bit of caution with this recommendation, as too often, these students work to support the family and may not be able to focus on academics.

Secondary School Administrators, Teachers, Counselors

If student agency and independence are critical for success, then high school administrators, teachers and counselors must create explicit programs that work to develop that mindset. As evidenced by the support needed to develop agency, secondary school administrators play a key role in the successful transition from high school to college. Many of these practices cannot happen without the support of the administration. Administrators need to develop the structure for current and former ELLs to succeed in this transition.

Mentor Programs

Mentor relationships have been shown to inspire students and keep students involved in school (Kostyo, 2017).

“Mentoring, at its core, assures students that someone cares about them and that they are not alone in dealing with challenges. Research from the National Mentoring Partnership (2019) confirms that quality mentoring relationships have powerful positive effects on high school students in a variety of personal and academic situations” (George, 2019).

Developing relationships with mentors will definitely provide support in building and sustaining agency. Working with a support team will help current and former ELLs overcome fears and learn to seek extra help. A personalized mentorship program can also assist throughout the college preparation and application process, as well as offer insight and motivation. However, a set time needs to be devoted for mentors to meet with their mentees. This can be accomplished by implementing a designated duty schedule and/or college prep block for students during the school day.

Instructional classes

Oftentimes, ELLs are not enrolled in grade level ELA classes. Model high school programs in New Jersey have created a double period of ESL with one period that addresses grade level ELA standards while the second period focuses on English language development skills (https://www.nj.gov/education/bilingual/resources/slr/). Some high schools have specifically instituted a transitional class for former ELLs. This transitional class would give the support in writing and grammar for their high school classes. Another option is to implement dual-credit college courses for ELLs to earn high school and college credit at the same time (Wetzel, 2012). In addition, encourage a focus on informal and formal writing throughout all content areas.

College Preparation

One of the concerns of College ESL Coordinators is that current and former ELLs often resist being required to take ESL courses at the college level, especially students who “exited” the ESL program in high school. One of the noted areas that need improvement is the use of functional grammar in academic writing. Investing in English grammar instruction at this level will pay dividends in college English classes. Therefore, schools should review and allocate funds for high-quality ESL materials to ensure that students receive consistent instruction in academic Writing, Reading, Speaking and Listening. Secondary schools should implement a bridge program to help current and former ELLs transition more smoothly to college. (McWhiter and Howard, 2019).

One suggestion is for high schools to encourage students to study for and take the Accuplacer in the fall in order to prepare students for college expectations. Students who do not do well initially on this exam would then take the Accuplacer diagnostic test to determine areas of difficulty. Schools could then offer students a class to strengthen their areas of weakness. In this way, students will have a better possibility of passing the Accuplacer Placement and thus avoid enrollment in remedial classes.

It is a huge task to support current and former ELLs in the transition from high school to college. Many variables impact this process. Cooperation and alignment is needed from all stakeholders. This is just the beginning of a requisite discussion regarding the academic success of ELLs and former ELLs in post-secondary education.

References

Bailey, T., Jeong, D. W., & Cho, S.-W. (2010). Student progression through developmental education sequences in community colleges (CCRC Brief No. 45). Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED512395

George, P (2019). Understanding high school English learners chronic absenteeism. Dissertation Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ.

Kostyo, S. (2017). Why every student should have a mentor. Retrieved from https://awareness.attendanceworks.org/mentor-real-life-attendance-week/

McWhirter, K., and Howard, E. (2019). “The College Transition Guide for ESL Students.” AffordableCollegesOnline.org, AffordableCollegesOnline.org, 19 Aug. 2019, https://www.affordablecollegesonline.org/college-resource-center/college-transition-guide-for-esl-students/.

NJTESOL-NJBE, Inc. (2008). Position paper Generation 1.5. Retrieved from https://www.njtesol-njbe.org

Wetzel, J. (2012). “Educational Trajectories of English Language Learners Examined.” Vanderbilt University, Vanderbilt University, 15 Mar. 2012,

https://news.vanderbilt.edu/2012/03/15/educational-trajectories-of-ell/.

Globalization To The Rescue!

By Pedro Trivella

Pedro Trivella is an Asbury Park School District ESL/Bilingual Educator.

Should we embrace Nationalism or Globalism as we guide our English Language Learners through their academic and acculturation process?

Should we embrace Nationalism or Globalism as we guide our English Language Learners through their academic and acculturation process?

If America’s DNA is intercultural, why has global education not played a greater role in our education system? For me, Globalism just comes as second nature. I was born and raised in Venezuela by a Puerto Rican/Venezuelan mother and an Italian father. Additionally, I moved to the United States at the tender age of 18 to learn English and to earn a college education.

Becoming a second language learner in a completely new culture has definitely been the most challenging and rewarding experience of my life. The most valuable lesson that I have acquired during my acculturation trajectory is realizing that for minority language children, it is not just about learning content in a second language, but it is also about building a strong identity that leads to empowerment and inclusion.

Leveraging the pertinent, and often-undervalued, aspect that culture plays in education has always guided my mission of education equity. Nonetheless, recently becoming a Teachers of Global Classrooms Fulbright scholar combined with our unprecedented remote learning reality, has strongly fueled my “Globalism to the rescue” mission. There is no denying that the devastating consequences that the Coronavirus has brought upon us has abruptly shed light on the valuable role that global education plays in our daily lives. Unfortunately, it took for such an unprecedented event to take place for us to realize that “what happens in China does not stay in China. Dr, Martin Luther King always knew that cultivating globalism was key in achieving borderless love and justice across the world. In “A Christmas Sermon on Peace” he said that “”Before you finish breakfast, you’ve depended on half the world” (King, 1967).

What is Global Education?

Globalism plays a pivotal role in cultivating equitable learning opportunities for our English Language learners. Fostering Global learning strategies empower EL students to actively participate in their academic, social emotional, and acculturation process. Fostering user friendly global tools enable educators to create 21st Century learning spaces that value and celebrate diversity and inclusion. When students visualize themselves as global citizens, they actively participate in their identity development, academic growth and citizenship engagement.

Global education embraces a comprehensive learning approach that promotes students’ curiosity, exploration, and awareness about the world and how it works. The Asia Society’s Center for Global Education’s article “Teaching for Global Competence in a Rapidly Changing World” (2018), substantiates that global competent students use the big ideas, tools, methods, and languages that are central to any discipline (mathematics, literature, history, science, and the arts) to engage the pressing issues of our time.

Globally competent students effectively combine knowledge about the world and critical reason to form their own opinion about a global issue. Learners who acquire a mature level of development in this dimension use higher-order thinking skills, such as selecting and weighing appropriate evidence to reason about global developments.

According to Boix Mansilla and Jackson (2011), global minded students can draw on and combine the disciplinary knowledge and modes of thinking acquired in schools to ask questions, analyze data and arguments, explain phenomena, and develop a position concerning a local, global or cultural issue.

Why Teach For Global Competence?

Inescapable economic, cultural, technological, environmental, and political forces are affecting every society on earth and making nations and peoples more interdependent than ever before. Responding effectively to these forces will require creative multinational solutions to be negotiated and carried out by individuals who can and do participate simultaneously in local, national, and global civic life. Put simply, if individuals and their communities are to thrive in the future, schools must prepare today’s students to be globally competent.

Educating for global competence increases students’ future employability. Effective communication and appropriate behavior within diverse teams are keys to success in many jobs, and will remain so as technology continues to make it easier for people to connect across the globe. Employers increasingly seek to attract learners who easily adapt and are able to apply and transfer their skills and knowledge to new contexts. Our world interconnected work environment expects young people to understand the dynamics of globalization (British Council, 2013).

I think we can all agree that we are living in a polarizing society where conflict is mostly viewed as the catalyst for divineness. I strongly agree with Rychen and Salganik’s theory that competent students approach conflicts in a constructive manner, recognizing that conflict is a process to be managed rather than seeking to negate it (Rychen and Salganik, 2003). Taking an active part in conflict management and resolution requires listening and seeking common solutions. Global education enables students to address conflict by analyzing key issues, needs and interests (e.g. power, recognition of merit, division of work, equity); identifying the origins of the conflict and the diverse perspectives of those involved in the conflict, recognizing that the parties might differ culturally; identifying areas of agreement and disagreement; and reframing the conflict to build consensus.

Global Education creates classroom environments that value diversity and global engagement. Consequently, it is particularly beneficial to ELs since it naturally motivates them to develop citizenship responsibilities and acquire new ways of saying, and doing.

Both OECD and the Center for Global Education have identified four key aspects of global competence. Globally competent youth:

- Investigate the world beyond their immediate environment, framing significant problems and conducting well-crafted research.

- Recognize perspectives, others’ and their own, articulating and explaining such perspectives thoughtfully and respectfully.

- Communicate ideas effectively with culturally diverse audiences.

- Take action to improve conditions, viewing themselves as players in the world and participating reflectively (The Asia Society’s Center for Global Education, 2018, pg. 5).

Some of the most successful Global Education Learning Strategies that I have routinely embedded in my lessons are:

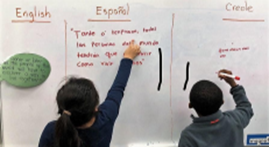

1. How Else & Why: How do global heroes/ambassadors say it? How else can I say it? Why is it important for me to embrace it? Identifying diverse ways to express important messages develops learners’ analyzing thinking skills and communication efficacy.

A summary of a Dr. Martin Luther King “My Dream, Your Dream, Our Dream” lesson is as follows:

- Students watched a video of Dr. King, which highlighted several of his quotes.

- Learners selected their favorite quotes and formed small groups based on their selections.

- Children analyzed, evaluated, and shared the messages that they perceived from their quotes.

- Each group translated their favorite quotes into its members’ home languages (Spanish and Creole)

- Students engaged in a journal writing independent activity in which they were able to use their own words to express their selected quotes’ message.

2. Comparative Approach: This enables learners to widen their multicultural agency by comparing and contrasting their own native countries’ events to other countries across the world.

A comparative approach activity that I implemented during Haitian Flag Month enabled all students to engage in authentic reflective practice.

Haitian native students interviewed their peers and staff members to identify the similarities and differences that exist among various cultures.

This student driven activity offered all children with opportunities to evaluate their own cultural lens while cementing the general consensus and message displayed in the Hatian Flag: “It is in our Unity that we find our Strength”

3. 3 Ys: Why is it important to me, my community, my nation and the world?

3. 3 Ys: Why is it important to me, my community, my nation and the world?

Nurturing students’ disposition to discern the significance of an issue by embracing the global strategy’s 3 Ys, proved to be quite effective during a “Should we ban plastic water bottles?” lesson. Learners evaluated the impact that plastic has on their personal lives, community beaches, and world’s sea life. Thereafter, a classroom vote took place, which facilitated a discussion regarding sustainable environmental support practices.

4. Circle of Action Routine: Engaging ELs in civic oriented activities propels them to develop a strong sense of self.

I agree with Bringle and Clayton (2012) that service learning is a powerful tool that can help students to develop multiple global skills through real-world experience. Students are able to apply and transfer acquired knowledge and skills into projects that benefit themselves, their family and friends, their community, and the world (Bringle and Clayton, 2012). After the activities, learners reflect on their service experiences and gain further understanding of course content, while enhancing their sense of role in society with regard to civic, social, economic and political issues. The “Fostering homeless animals” Pre-K activity below demonstrates that children are never too young to embrace, value, and practice empathy. Through service learning, these young students are not only “served to learn,” which is applied learning, but also “learned to serve”.

I agree with Bringle and Clayton (2012) that service learning is a powerful tool that can help students to develop multiple global skills through real-world experience. Students are able to apply and transfer acquired knowledge and skills into projects that benefit themselves, their family and friends, their community, and the world (Bringle and Clayton, 2012). After the activities, learners reflect on their service experiences and gain further understanding of course content, while enhancing their sense of role in society with regard to civic, social, economic and political issues. The “Fostering homeless animals” Pre-K activity below demonstrates that children are never too young to embrace, value, and practice empathy. Through service learning, these young students are not only “served to learn,” which is applied learning, but also “learned to serve”.

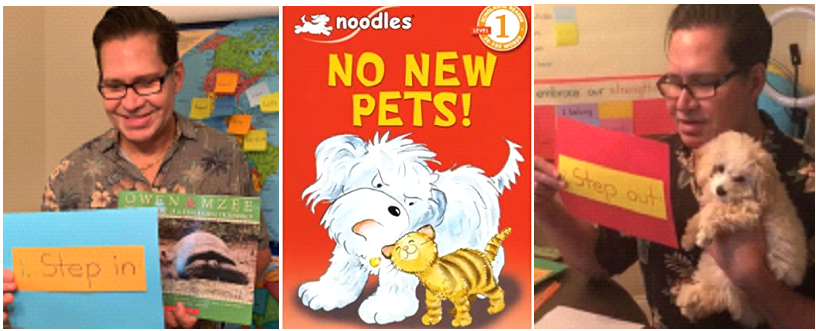

5. Step In – Step Out – Step Back In: This global routine challenges students to reflect and evaluate on the potential misconceptions they may form when meeting people (particularly ones that come from different ethnic backgrounds) for the first time.

I share Fennes and Hapgood’s (1997) view that the ability to see through ‘another cultural filter’ provides opportunities to deepen and question one’s own perspectives, and thus make more mature decisions when dealing with others. In this activity shown below, my first grade virtual summer school students effortlessly embraced it after we read “Owen & Mzee”, a story about a real life friendship that was formed between two unlikely animals in Africa. Some of the students even connected and applied this strategy to another previously read story “No More Pets”, as well as a challenge that I was experiencing at home between my old dog “Pancho” and my new pet “GiGi”.

You do not need to be an expert on every global issue to educate your students in global citizenship. It is much more important to have an ongoing willingness to embrace routines that help students develop intercultural agency. To view how the learning strategies mentioned above are conducive to support Common Core Standards, learners’ objectives, and be effortlessly implemented in multiple subjects, please refer to Dr. King’s lesson I presented at the New Jersey TV Learning Live.

Global Education creates equitable learning experiences for all students through cultural connections and cohesiveness. Fostering global competence among all learners, both ELs and mainstream students, is interconnected and simultaneously serves two purposes. Offering our EL students a learning space where their multicultural backgrounds are viewed and embraced as assets by all stakeholders enables them to holistically develop strong identities. Additionally, Global education equips monolingual learners with the intercultural and 21st Century efficacy needed to become productive members of our diverse and evolving intercultural society.

My redesigned mission of empowering EL students with equitable education and life opportunities is guided by the following belief: As we pursue our American Dream, we must first and foremost embrace our unique essence, develop strong identities, voices, and moral compass. Only then, we will be able to enrich our lives and positively impact our communities, Nation, and World.

References:

Boix Mansilla, V. and A. Jackson (2011), Educating for Global Competence: Preparing Our Youth to Engage the World, Asia Society and Council of Chief State School Officers.

Bringle, R. G. and P. H. Clayton (2012), “Civic education through service-learning: What, how, and why? in L. McIlrath, A. Lyons and R. Munck (eds.), Higher Education and Civic Engagement: Comparative Perspectives, Palgrave, New York, pp. 101-124.

British Council (2013), Culture at Work: The Value of Intercultural Skills in the Workplace, British Council, United Kingdom.

Fennes, H. and K. Hapgood (1997), Intercultural Learning in the Classroom: Crossing Borders, Cassell, London.

Going Global: Teaching for Global Competence in a Rapidly Changing World. OECD /Asia Society, 2018.

https://asiasociety.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/teaching-for-global-competence-in-a-rapidly-changing-world-edu.pdf

King, Martin Luther (1967), “A Christmas Sermon on Peace.” Massey Lectures. Massey Lectures, 1967, Atlanta, Georgia, Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Rychen, D. S. and L.H. Salganik (eds.) (2003), Key Competencies for a Successful Life and a Well-Functioning Society, Hogrefe and Huber, Göttingen, Germany.

To Google Translate or Not Google Translate?

By Amanda Guarino and Angello Villarreal

Amanda Guarino and Angello Villarreal are Monmouth University Doctoral Candidates.

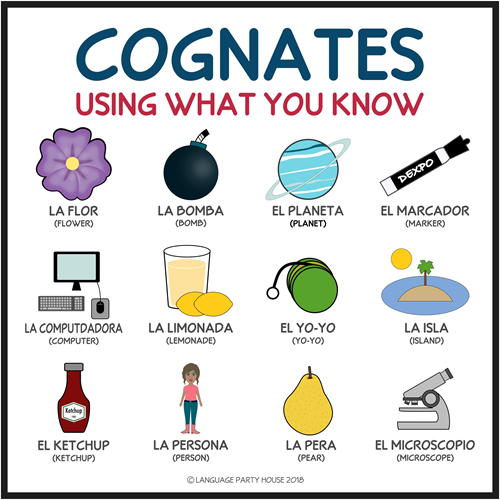

English language learners are faced with three daunting challenges: acquiring a new language, building academic knowledge in various subject areas, and bridging social connections with peers and school faculty. While Google Translate could be useful in some scenarios, educators should be aware that some translations could not have the meaning intended (Ex. Paper Jam – Mermelada de Papel (a Spanish-speaker would understand: Paper’s Marmalade). In general, this can be extremely difficult, especially for language learners of lower proficiency levels; regardless, it is evident that discovering similarities between the native language and the target language often brings comfort and boosts confidence when tackling these tasks. Furthermore, incorporating the native language creates a culturally inclusive classroom in which different languages are celebrated and preserved, as opposed to being replaced with English.

Using a student’s native language in an English as a New Language class setting can be very controversial, depending on the students’ academic proficiency in the native language. Some may argue that using cognates and translations in the classroom is ineffective, as students who have experienced interruptions in formal education (SIFE/SLIFE) may not have the background knowledge needed in the native language to decode the cognates presented in the target language. However, using cognates and translations for students who have a solid academic foundation in their native language can be extremely beneficial, as it allows students to bridge connections between their native language and the target language; this academic bridge enables classroom instruction in various subject areas to become more accessible to language learners, which will lead to an increase in academic success.

Educational researchers have determined that prior knowledge in one’s home language plays an influential role in acquiring a second language, as building connections between the native language and the target language fosters a deeper understanding (Collier and Thomas, 2017). Language acquisition stretches far beyond the simple memorization of the language; when students are able to truly understand the patterns and grammatical structures of the target language, they are able to use it to its fullest potential and naturally memorize it (Collier and Thomas, 2017). Teaching students to identify similarities between word sound and letter structures within cognates allows students to decode the meaning behind the word in the target language.

Utilizing cognates allows students to gather a general sense of the instruction at hand, increasing the likelihood of engagement and participation. As engagement and class participation increases, so does academic performance. For example, if a high school English Language Arts teacher were to teach the theme of reminiscence throughout The Great Gatsby, most language learners might encounter confusion. Students may be stumped right from the start, which may result in a need to redirect the lesson from literary analysis to breaking down academic vocabulary. This sets the class back and often discourages students. On the other hand, if the teacher chose to use the synonym “nostalgia” instead, Spanish speaking English Language Learners would most likely recognize the written form of the word, as it is spelled the same exact way in English and Spanish. Though these words are pronounced differently in both languages, /nɒˈstældʒə/ in English and /nohs-tahl-hyah/ in Spanish, language learners understand the meaning of the word and have a base to build upon. They are now able to continue to progress throughout the lesson contributing to class discussions and other activities. The teacher can also introduce the word “reminiscence” as a synonym to “nostalgia” later on in the lesson, building on students’ academic vocabulary at a more effective rate. Various studies have indicated that teaching cognate strategies to English Language Learners makes reading comprehension and inferencing definitions of unknown vocabulary much more accessible, increasing student progress and improvement in these areas (Dressler, 2008; Ramirez et. al. 2013; Sunderman and Schwarts, 2008). Just as cognates make reading comprehension and decoding vocabulary more accessible for language learners, the same appears to be true with speech and pronunciation, based on multiple research studies (Amengual 2012; Tessel et. al 2018). The visual similarities of cognates indicate to language learners that the pronunciation of the words are similar as well (Amengual 2012; Tessel et. al 2018).

Though utilizing cognates in content instruction has many advantages, this strategy can only work if students have a strong literacy foundation in their native language. Due to many extenuating circumstances beyond the control of students, families, and educators, many students around the world are facing interruptions to their formal education. Some of these factors include war, poverty, and displacement; though these factors are completely out of their hands, students are directly impacted and face many educational setbacks. Due to the education gaps, some students with interrupted formal education (SIFE/SLIFE) may not be able to read or write in their native language (Roberston and Lafond, 2008). Furthermore, they may lack an understanding of basic knowledge and skills that their peers have already acquired (Roberston and Lafond, 2008). Therefore, utilizing cognate strategies will not work by themselves with this particular group of students; if a student does not have the knowledge in their native language, they cannot bridge connections to the target language. However, educators can use visuals to introduce the concept of cognates to students in both the native language and the target language. For example, the term “biography” in English translates to “biografía” in Spanish; a student with interrupted schooling may not know what this term means in the target language or the native language. Nonetheless, if the educator provides a visual representation of an autobiography along with the terms in both English and Spanish, at the very least, students will be able to come to the realization that an autobiography is a type of book. After exploring the visual and discussing it further in class, students will eventually come to the conclusion that an autobiography is a story of a person’s life written by that person. Another example includes the terms “constellation” and “constelación;” once again, a student with interrupted schooling may not recognize this word in either language. Yet, providing the student with a visual representation of a constellation and pairing it with cognates will allow the student to infer that a constellation refers to stars. The teacher can take this understanding one step further, by showing comparative visuals of a single star versus a constellation of stars; this will lead the student to conclude that a constellation refers to a group of stars. Though implementing cognates by themselves may not work for students with interrupted education, providing visual images to complement these terms serves as a breakthrough to that barrier.

Activating a student’s prior knowledge by incorporating the native language into daily instruction holds a multitude of benefits which include a more comprehensive understanding of the learning goals, an increase in student confidence, and a preservation of the native language and culture. Utilizing cognates, and pairing them with visuals when necessary, serve as a stepping stone for language learners, unlocking the main idea of concepts throughout various content areas and providing an opportunity for a more thorough understanding through discussion, direct instruction, and independent practice.

References

Amengual, M. (2011). Interlingual influence in bilingual speech: Cognate status effect in a continuum of bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(3), 517–530. doi:

10.1017/s1366728911000460

Collier, V.P., & Thomas, W.P. (2017). Validating the power of bilingual schooling: Thirty-two years of large-scale, longitudinal research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37,

1-15. PDF

Dressler, C. (2000). The word-inferencing strategies of bilingual and monolingual fifth graders: A case study approach. Unpublished qualifying paper, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA.

Ramírez, G., Chen, X., & Pasquarella, A. (2013). Cross-Linguistic Transfer of Morphological Awareness in Spanish-Speaking English Language Learners. Topics in Language Disorders, 33(1), 73–92. doi: 10.1097/tld.0b013e318280f55a

Sunderman, G., & Schwartz, A. I. (2008). Using Cognates to Investigate Cross-Language Competition in Second Language Processing. TESOL Quarterly, 42(3), 527–536. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00145.x

Supporting ELL Students with Interrupted Formal Education (SIFEs). (2018). The ELL Teachers Toolbox, 345-349. doi:10.1002/9781119428701.ch35

Visit our home page for links to past and present Voices issues.

Visit our home page for links to past and present Voices issues.

Figure 1. Untitled comic of hand waving from under water (

Figure 1. Untitled comic of hand waving from under water (

Should we embrace Nationalism or Globalism as we guide our English Language Learners through their academic and acculturation process?

Should we embrace Nationalism or Globalism as we guide our English Language Learners through their academic and acculturation process?

3. 3 Ys: Why is it important to me, my community, my nation and the world?

3. 3 Ys: Why is it important to me, my community, my nation and the world? I agree with Bringle and Clayton (2012) that service learning is a powerful tool that can help students to develop multiple global skills through real-world experience. Students are able to apply and transfer acquired knowledge and skills into projects that benefit themselves, their family and friends, their community, and the world (Bringle and Clayton, 2012). After the activities, learners reflect on their service experiences and gain further understanding of course content, while enhancing their sense of role in society with regard to civic, social, economic and political issues. The “Fostering homeless animals” Pre-K activity below demonstrates that children are never too young to embrace, value, and practice empathy. Through service learning, these young students are not only “served to learn,” which is applied learning, but also “learned to serve”.

I agree with Bringle and Clayton (2012) that service learning is a powerful tool that can help students to develop multiple global skills through real-world experience. Students are able to apply and transfer acquired knowledge and skills into projects that benefit themselves, their family and friends, their community, and the world (Bringle and Clayton, 2012). After the activities, learners reflect on their service experiences and gain further understanding of course content, while enhancing their sense of role in society with regard to civic, social, economic and political issues. The “Fostering homeless animals” Pre-K activity below demonstrates that children are never too young to embrace, value, and practice empathy. Through service learning, these young students are not only “served to learn,” which is applied learning, but also “learned to serve”.

Visit our

Visit our