NJ Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages/ NJ Bilingual Educators

Welcome to NJTESOL/NJBE’s Annual Voices Journal. This publication is a representation of members’ thoughts on issues important to ESL, Bilingual, and Dual Language educators in New Jersey and the larger language teaching community. This annual journal has a scholarly approach which reveals the deep commitment our writers and readers have for their teaching practice and students. NJTESOL/NJBE hopes you enjoy our second issue of NJTESOL/NJBE’s Annual Voices Journal and its continuing companion, NJTESOL/NJBE’s Weekly Voices.

Annual Voices Journal is the official publication of NJTESOL/NJBE, issued annually each winter. Articles in the NJTESOL/NJBE Voices Journal include current issues, classroom explorations, program description/exemplary scheduling, and alternative perspectives as related to the teaching of English to speakers of other languages, Bilingual Education, and Dual language programs including students who are U.S.-born bilinguals, “generation 1.5”, immigrants, and international students. Articles may focus on any educational level, from kindergarten to university, as well as on adult school and workplace literacy settings.

ARTICLES:

A Principal’s Framework for Supporting MLLs

Alex Guzman

A framework for high school principals to support MLLs: Alex Guzman, a former principal, shares a practical approach to serving MLLs and learning to address their needs.

Translanguaging: An Inexperienced Teacher’s Guide to Implementation

Christine Donatello and Chiu-Yin (Cathy) Wong

A reflection of exploration following a teacher’s inexperience with the concept of translanguaging through her journey of adapting it into her classes and witnessing positive results. It provides tips for teachers to use to implement translanguaging in their own classrooms along with the reasons for doing so to create an equitable education for emergent bilingual students (EBs). A workshop will be presented by the authors at NJTESOL/NJBE Spring Conference 2023.

Curriculum-Thinking around the 2020 WIDA Standards Framework

Margaret Churchill & Hana Prashker

Using the principles of backward design, educators can plan and create units and lessons that implement the big ideas of the 2020 WIDA Standards Framework by examining released ACCESS for ELLs test items. These tasks by grade level cluster serve as design models as we consider how to put the WIDA Standards Framework into practice in our own classrooms. A table provides a focus for unit planning around the Key Language Uses that are prevalent in grade-level clusters.

How Does Sara Think?

Tina Kern

In our educational community today, students seem to be experiencing what is considered a “learning loss”. As a result, data has become more important as a measure of growth. This mindset has sent the message to students that, above all, the correct answer is valued. In this atmosphere, the concept of learning the process of achieving the answer, instead of just submitting the correct answer, has diminished. How do we step back and spend time assisting our students with strategies so that they learn the value of the process, of the “why”, instead of just submitting the answer?

Save Time! Streamline Your Unit and Lesson Planning Using the WIDA Standards Digital Explorer

Lynn Shafer Willner

Saving 10 minutes a day can add up to 30 hours a year. Are you looking for ways to save time without skimping on the quality of your unit and lesson planning? This article suggests three time-saving tips for using the WIDA Standards Digital Explorer as part of your design process including Identifying unit goals for language development, selecting Proficiency Level Descriptors and/or Language Functions and their associated Language Features for language lesson objectives, and locating standards-aligned digital resources.

Science Education for All: Integrating Science Content Attainment and Language Development for ELLs

Cecilia Vila

An overview of how to integrate academic language development and content attainment through a collaborative approach. The focus is to provide an example for educators in grades K-8 whose students are English Language Learners who may or may not share the same home language. It provides a snapshot of the interactive workshop with the same title presented by Ms. Vila Chave at the 2022 NJ Science Convention, at NABE 2023 and the NJTESOL/NJBE Spring Conference 2023.

Cooperative Teaching Notetaking Model

Bryan Meadows

A professional reflection on a note-taking technique a push-in ESL teacher is using in a high school Biology classroom emphasizing content-area vocabulary using shared digital notes.

A Principal’s Framework for Supporting MLLs

By Alex Guzman

Throughout my leadership journey, I have seen different practical approaches to address the needs of all learners. As a high school principal, I read educational practitioner and research articles, conducted research, and spoke to colleagues with more experience than I had to learn from their lessons. Driven by my inquiry approach and guided by my wonder, I knew I needed to establish my foundation to support my students and teachers.

As a bilingual student, the equitable education of bilingual students is one of my drivers. The increasing number of Multilingual Language Learners (MLLs) in the United States, New Jersey, and school districts have provided us with an excellent opportunity to build community and provide MLLs with the power of language and instill in them a love for learning. Knowing that MLLs’ education is a multifaceted and complicated endeavor, I always wondered what other high school principals are doing to address the needs of MLLs.

An MLL’s profile can vary from newcomers to the country, some who have been in the US public schools for 2-3 years, and some who are “long-term” MLLs. Regardless of where they are in their journey, they are my students. Yes, we have federal, state, and local accountability measures, but these are the minimum standards. As a high school principal, knowing I only have four years, sometimes less, to prepare them to graduate from high school and set them up for success in the next chapter of their lives, no matter what that may be, the minimum was not going to do it. I needed guidance, research, and something practical. My wonder helped me develop a simple yet practical framework to support MLLs while addressing the high school principal’s many responsibilities.

The Framework

The framework starts at the center and focuses on getting to know my MLLs. My goal was to gather specific information by the end of September. Weekly meetings would be scheduled with the ESL teachers, school counselors, and the Child Study Team, if applicable. Sometimes we would meet all together, while other times we met separately. The specific questions used to gather information are listed below. The three different categories of information, developmental needs, family conditions, and neighborhood conditions, would provide me with an idea of the social context my MLLs grew up in. We focused on the listed factors which impact Latinx children’s growth and development because most of our MLLs were from Latin America and Spanish speaking. (Guandera & Contreras, 2009). Most of my experience was with Spanish-speaking MLLs.

Developmental Needs

- Has the student sought out the nurse for some health care?

- Has the student exhibited signs of needing mental health counseling?

- Does the student purchase or come with lunch? Breakfast?

- Do we have primary language translators available for students and parents?

- How does the student see themself within the school community? Greater community?

Family Conditions

- What is the parents’ educational background?

- Does the student receive free/reduced lunch?

- Do they have siblings in the school? District? What is the family structure?

- Does the student know which classes prepare one for college? How to get involved, and what activities can lead to opportunities beyond school?

- Does the student know how things work at the high school level?

- How long has the student been in the ELL program? District? The state? Country?

Neighborhood Conditions

- Where do they live? What part of town?

- Is there a need for community and county resources?

- Are they involved with any institutions outside school, i.e., sports, religious institutions, and community groups?

- Who are they surrounding themselves with?

Meetings would be structured to discuss the points mentioned above, and I would collect the information in a Google Doc for accessibility. We were building an “MLLs baseball card,” but it is not just about numbers. It is about the individual’s assets and building empathy among team members.

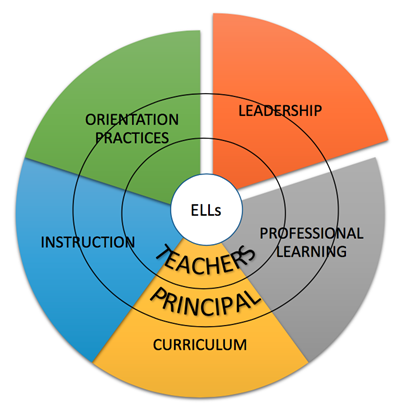

As the figure below illustrates, five components impact our ELL’s high school experience and are affected by the behaviors of the adults in the school community: 1) Orientation Practices, 2) Curriculum, 3) Instruction, 4) Professional Learning, and 5) Leadership. As the principal, I coordinated my actions and induced adults in the school community to incorporate the five components in their thinking and actions. However, this article highlights my intentional actions and interactions with ESL and content area teachers, counselors, and CST.

Figure 1. Framework for Supporting English Language Learners

Orientation Practices

Orientation practices, those actions that introduce MLLs to their learning and socializing environments and the school community, are essential as they introduce how we do things. MLLs will get an initial feel of the school culture through their observations of artifacts, which only tell part of our story and are challenging to understand (Stein, 2006).

Although there are many layers to orienting our MLLs to the school community, I paid attention to three aspects: access to the principal, parent visits, and communications. Firstly, I made my presence known, showed them I was there to listen and walked with them. I would make frequent stops in their classrooms, both ESL and content areas, make eye contact, and sit next to them. Although I was an ELL student, I knew their experience was different from mine and did not want my bias to get in the way. While walking the halls between classes, I always asked, “How can I, as the principal, support you?” At first, I would get a nod indicating no or nothing; eventually, they would open up, asking simple questions. My goal was to earn their trust. I knew I gained their trust when they sought me out.

Secondly, when ELL’s parents visit the school, I ensure I get an opportunity to meet them, even if it is for 30 seconds. I asked the school counselors and CST to inform my secretary or me when an ELL parent was scheduled to come in. I always felt that if they saw the principal welcoming them into his home, they would remember a pleasant and personable experience and start building trust. It was my opportunity to put a face to a name, and even if I did not speak their language, it showed I was there to listen, help, and support them. If I could not make it, I would ensure I informed a building-level administrator, whether it was an assistant principal, a supervisor assigned to my building, or an athletic director. I would ask them to make a simple gesture to welcome them.

Thirdly, pay attention to what communications to parents of MLLs. MLLs and their families have diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds and experiences. They may not have the “cultural capital” to help them determine how to navigate the high school experience best. I would follow up with the student to ensure they receive all communications and address any questions.

A Principal’s Framework for Supporting MLLs and the other articles continue below.

Curriculum

In conversations with ESL and content area teachers, I focus on the WIDA Standards, Can Do Descriptors, and Content Area Curricula. The WIDA Language Development standards (WIDA, 2020), from my experience, are less well-known among non-ESL teachers than they are. These standards are equally as important as the New Jersey Student Learning Standards (NJSLS). The teachers and I unpacked the WIDA Standards and Can-Do Descriptors (WIDA, 2020), a process that we found valuable. The Can-Do descriptors helped my staff visualize what MLLs can do in the four domains. It made it more concrete for content area teachers. It also helped us realize that we must change our deficit-based perspective to an asset-based one (Scanlan, 2007). With the new 2020 WIDA standards and the news that the organization may do away with the Can-Do-Descriptors, I will look to find out how we can make the standards more user-friendly.

As teachers and I developed a common language around what MLLs “Can Do,” we transitioned the conversations to identify the language for math, science, language arts, and social studies. We dug deep and examined academic language development in different content areas. I asked my teachers to identify the respective academic language’s attributes explicitly. These were long-term conversations in department meetings and PLCs, intending to change their planning and instruction.

Instruction

My conversations regarding instruction started with data to inform teachers’ instructional planning decisions. I introduced some primary data on MLLs’ language proficiency levels and filled them in with the information gathered from my conversation with school counselors and CST. However, the numbers are not the end-all, be-all. My next step was to conduct a task analysis. City et al. (2009) state in “Principle #3: If you can’t see it in the core, it’s not there.” The task analysis examined the relationship between the student, teacher, and content as students completed a learning task. The fundamental question here is, what were we asking students to do? The analysis helped us understand both the content and language demands of the learning tasks and how we can explicitly incorporate language development strategies and scaffolding language learning to address those demands. We took it slow at first to develop a common language around academic language and communication. Cummins (2014) argues “that students will gain expertise in understanding and using academic language when instruction engages them in the co-construction of knowledge and provides opportunities for them to use academic language for intellectually powerful purposes.” (p.146)

Professional Learning

As defined by Fullan and Quinn (2018), “deepening learning” was my driver as I empowered my staff. The one element of deepening learning that I focused on was “shift practices through capacity building.” I knew learning besides them would be vital in changing mindsets and practices. Learning together, showing them that we will make mistakes, and supporting them through failures was an essential part of the process. My goal with professional learning was working collaboratively with district-level administrators to bring in professional learning opportunities that aimed for transformational change by increasing teacher knowledge, changing attitudes, developing skills, and developing teacher aspirations to ultimately change behaviors that maintain the status quo (Killion, 2017).

Leadership

As a leader, I always look to learn from others because everyone can add value to our professional and personal lives. My conversations with my ESL teacher and content area teachers were always critical because they allowed me to learn about the students and the teacher themselves and continue building our relationship. As a high school principal, I knew I had to model what I wanted to see from my teachers. Modeling an inquiry approach, a love for learning, problem-solving, and collaborating is what I value. Therefore, I would always make time to meet with the teachers throughout my week and day to talk specifically about our MLLs.

I share this framework as a compass to guide my fellow high school principals as they lead and manage many responsibilities. I hope that high school principals start conversations focused on MLLs and build on this framework because “communication is not merely an exchange of information but an act of power.” (Genesee et al., 2005)

References

City, E. A., Elmore, R. F., Fiarman, S. E., Teitel, L., & Lachman, A. (2018). Instructional rounds in education: A network approach to improving teaching and learning. Harvard Education Press.

Common Core State Standards (Washington, D.C.: National Governors Association and Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010).

Cummins, J. (2014). Beyond language: Academic communication and student success. Linguistics and Education, 26, 145-154. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2014.01.006

ELSF: Resource: Analyzing Content and Language Demands. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.elsuccessforum.org/resources/math-analyzing-content-and-language-demands

Echevarría, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D. (2017). They are making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP Model. Pearson.

Fullan, M., & Quinn, J. (2016). Coherence: The right drivers in action for schools, districts, and systems. Corwin.

Gandara, P. C., & Contreras, F. (2010). The Latino education crisis: The consequences of failed social policies. Harvard University Press.

Genesee, F. (2008). Educating English language learners: A synthesis of research evidence. Cambridge University Press.

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching English language learners in the mainstream classroom. Heinemann.

Killion, J. (2017). Assessing impact: Evaluating staff development (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Next Generation Science Standards. (2020, October 01). Retrieved from http://nextgenscience.org/

Schein, E. H. (2006). Organizational Culture and Leadership: CafeScribe. Wiley

WIDA’s 2012 Amplification of the English Language Development Standards, Kindergarten–Grade 12 (“WIDA ELD Standards”). (Version 1.6 Revised 2/6/17). Retrieved from https://wida.wisc.edu/

WIDA’s 2020 English Language Development Standards, Retrieved from https://wida.wisc.edu/

Translanguaging: An Inexperienced Teacher’s Guide to Implementation

By Christine Donatello and Dr. Chiu-Yin (Cathy) Wong

This paper documented Christine Donatello, a monolingual, English as a new language (ENL) educator’s experience with implementing translanguaging. She described her journey from not knowing what translanguaging was, having doubts about the theory/pedagogy, to implementing it. Through pedagogical translanguaging, Christine witnessed her students progress academically and expand their language repertoires. She also developed a strong rapport with her students as a result of implementing pedagogical translanguaging. Due to her translanguaging knowledge gained from her teacher preparation program and implementation of it, she developed a strong translanguaging stance and believed that translanguaging is a foundation to create an equitable education for emergent bilingual students (EBs).

The start of her translanguaging journey

Christine was a first-year ENL teacher when she first learned about translanguaging. After graduating with her bachelor degree in History, she watched current events unfold and quickly realized that there was a group of underserved students who were in dire need of compassionate teachers who understood their needs. These students are referred to as EBs, according to Garcia (2019). Needless to say, she applied for her ENL certification and started attending graduate classes. She was hired in August 2020 as an alternate route teacher in the middle of the pandemic lockdown, and that was before her ENL coursework began. She had no previous background with EBs and was coming into the profession as a clean slate, so to speak.

She gobbled up as much information as she could in her first semester of graduate school, and it is here that she was introduced to translanguaging. The concept of translanguaging originally came from the term “trawsieithu”, coined by a Welsh bilingual education scholar. The purpose was to develop students’ bilingualism in Welsh and English through pedagogical practices (Williams, 2002). Garcia (2009) expands the notion of translanguaging with a social justice orientation in the US and stresses the importance of protecting minoritized languages of EBs by viewing their linguistic resources as an asset. Otheguy et al (2015) later define translanguaging as “the deployment of a speaker’s full linguistic repertoire without regard for a watchful adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named languages” (p. 283).

Christine admits that she approached the theory/pedagogy with hesitancy, fear, and perhaps a bit of disbelief in the beginning. She felt she had to have total control or as García et al (2017) refer to as “locus of control” over what was being said in the classroom. She soon learned that the goal of translanguaging is not to produce two monolinguals. Rather, bilingualism is fluid and dynamic (García et al, 2017) and the languages we speak become part of our identity, and translanguaging aims to empower students’ identities as bilinguals.

Deep rooted in the traditional monolingual ideology, Christine’s initial belief toward teaching her EBs was “English only.” She approached her classes with a traditional monolingual ideology and quickly realized this was an ineffective approach. Her students would barely talk to her or participate. A girl, named Anna (pseudonym), would not interact with her at all. Christine was desperate; she had to change something for the sake of her students.

Pedagogical translanguaging allows teachers to put this theory into practice. Focusing on multilingualism, pedagogical translanguaging refers to planned strategies and activities for EBs to acquire content and language knowledge through utilizing their full linguistic repertoires (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022). A translanguaging space is a safe space for students’ languages, cultures, and identity to take center stage. However, implementing translanguaging does not mean that teachers need to speak students’ home languages (L1s) in order to teach them effectively. Translanguaging emphasizes co-learning, where teachers and students work together to achieve learning outcomes (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022). Her professor, Cathy Wong, also created a co-learning environment where students were able to ask questions, discuss, and share their experiences in their learning journey of translanguaging. As such, the theory/pedagogy started making sense to her. However, would her administration feel the same? She broached the topic with her leaders at school, and they advised her that this was not a pedagogy that should be used regularly in the classroom. Disappointed, she found herself at a crossroad. After much contemplation and with the ongoing guidance and support from Professor Wong, Christine felt like she owed it to her students to move forward with translanguaging.

As soon as she started implementing translanguaging, she began seeing results. She first welcomed the students’ language and culture into the classroom by announcing that she would no longer require English only for anything. She told them they could use any languages to complete assignments. The students happily typed away, and more classwork was turned in that day than ever before. Anna handed hers in, and it was a beautifully written, lengthy paragraph in her L1. Though she still would not interact with her teacher, Christine knew they were off to a good start.

Then, she made connections between students’ L1s and English in her instruction in order to develop their metalinguistic awareness, a goal of pedagogical translanguaging. Doing so would benefit the students both linguistically and from a social-emotional standpoint. For example, Christine would look at each student’s writing assignment and point out certain Spanish words that she knew were cognates, asking her students to identify them in English. In this process, She was introducing them to cognates, and she was developing students’ linguistic awareness.

The end result

Time moved forward and a fantastic phenomenon was occurring. Christine’s classroom was getting messier but in a beautiful way. The students would have side conversations, they would delve off topic and they would start chattering away in their L1, and Christine – not knowing a word of Spanish – watched as language and communication flourished between her once silent students. A few would jump in and explain things in their L1 if her EBs needed assistance; they bounced word meanings back and forth off each other to make sense of topics. She surrendered control and let the corriente take the class in whatever direction it was going, and everyone flourished because of it.

The students who were in regular attendance shared with the others how inviting the environment had become, and more students began attending. In this translanguaging space, Anna started having full conversations with Christine. Anna would speak and write using all of her communicative repertoires and happily showed her pet to the class. Through pedagogical translanguaging, this once silent student finally felt comfortable. She and the other students could feel that their voices are valued, and they responded to it.

Tips for implementing translanguaging in your classroom

As mentioned, one of the goals of pedagogical translanguaging is to raise their metalinguistic awareness. One way to do so is to teach students to find cognates between the languages (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022). Teachers should also make good use of multilingual resources, multi-modalities (e.g., visuals, audios, technology), and semiotic resources, such as gestures (Lin, 2019) to create a translanguaging space. For example, Christine had students listen to a recording in English with pictures in the meaning making process. They would then work in pairs to connect the L1 words to the newly learned words. During this activity they often communicated in Spanish to make connections to the English word. As far as semiotic resources are concerned, she often uses grandiose theatrics to communicate meaning between the content they have learned in their L1 while connecting it to English. For example, in a unit about weather, Christine acted out the various types of weather conditions and then provided the English word. The students, often amused by her antics, remembered her demonstration and connected it to their L1 while hearing the word in English.

Quick reference guide: strategies for creating a translanguaging classroom

- Know your students. Take some time to learn about their languages, customs, and show a genuine interest in their lives.

- Research cognates and introduce them. If words in your students’ L1 and L2 have cognates, introduce these words to your students.

- Do not restrict their language usage. Even if the concept seems intimidating, make the decision to try it. If it is a writing assignment, allow your EBs to complete it in their L1. Then reinforce those cognates, and point out the common words between English and their L1 in their writing.

- Treat their multilingualism as an asset. Sometimes educators view an EB’s learning as a hindrance (García et al, 2017). EBs are embarking on a very important journey – multilingualism. As they expand their linguistic repertoires, they are preparing to thrive as global citizens in this multilingual world. Praise them for their efforts!

.

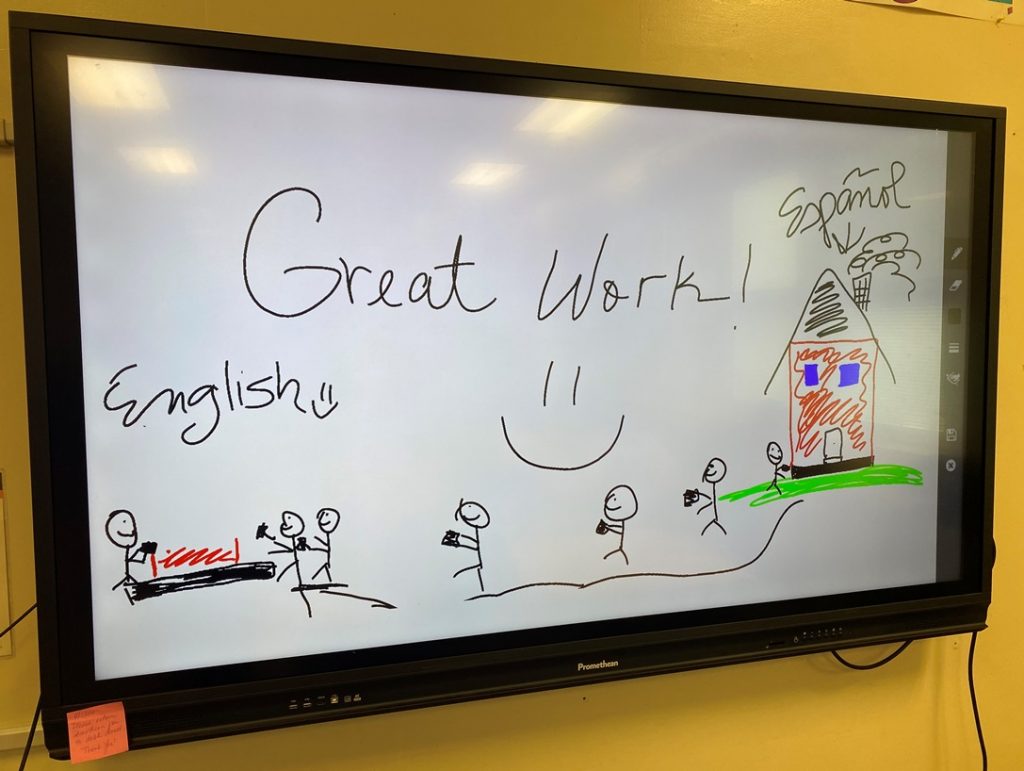

Note: Figure 1. is something Christine drew on the Promethean board for her EBs recently. She explained to them how to use context clues, and how as they build their house in English, they are going to use their foundation in Spanish. To give them a visual, she drew a fully completed house representing their L1 (Spanish), and the beginnings of their house in English. The little people are bridging the two houses together, happily carrying over the pieces of the foundation from their L1 house to build their L2 house.

Figure 1. Christine’s Translanguaging Visual

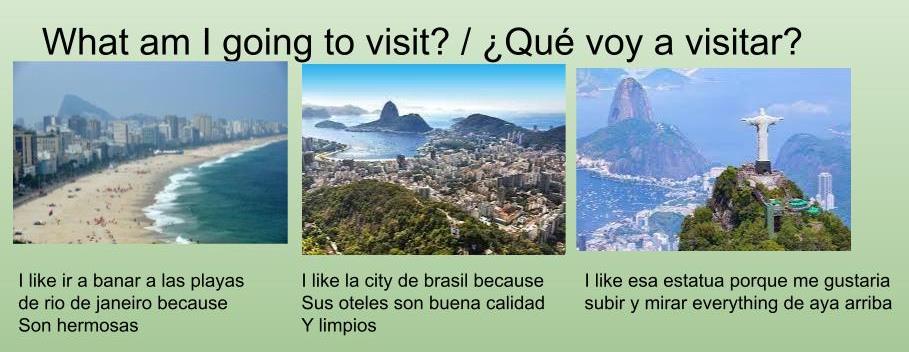

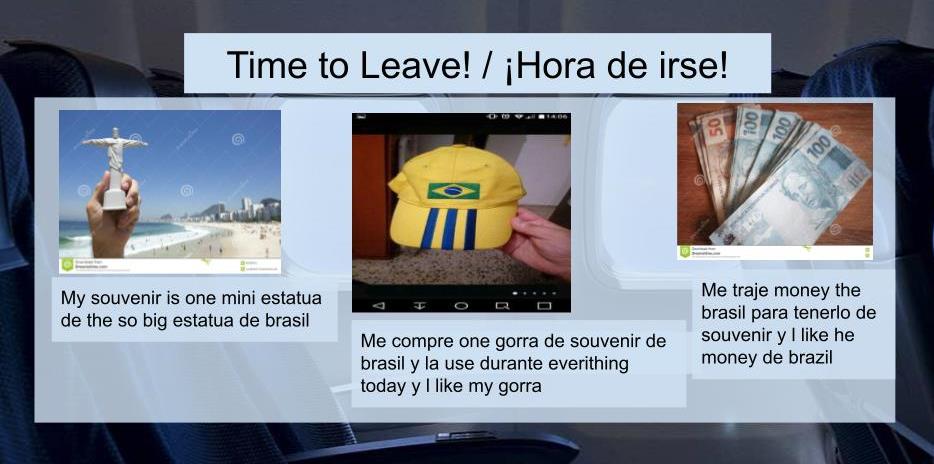

Figure 2 – 3. This student completed a project using translanguaging (see figures 2 and 3). The concept was that students were going on a global vacation to another country. He picked Brazil as his vacation spot. As he wrote, he switched from Spanish to English to reflect the words that he had learned. When he did not know the English word, he switched back to Spanish.

Figure 2. The three places he was planning to visit in Brazil.

Figure 3. The end of his vacation and the three souvenirs he was bringing home with him.

References

Budiman, A., Tamir, C., Mora, L., & Noe-Bustamante, L. (2020, October 1). Facts on U.S. immigrants, 2018. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/20/facts-on-u-s-immigrants/

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2022). Pedagogical Translanguaging and its Application to Language Classes. RELC Journal. http://doi.org/10.1177/00336882221082751.

García, O., Johnson, I. S., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning (1st ed.). Caslon Publishing.

García, O. (2009). Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century. In: Ajit Mohanty, Minati Panda, Robert Phillipson and Tove Skutnabb-Kangas (eds). Multilingual Education for Social Justice: Globalising the local. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, pp. 128-145.

Lin, A. M. Y. (2019). Theories of trans/languaging and trans-semiotizing: implications for content-based education classrooms. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(1), 5-16.

Otheguy, R., García, O., & Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review,6 (3), 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

The Author – Christine Donatello is a first generation American high school ESL teacher, as well as an instructor of adult ESL classes for the County College of Morris’ Workforce Development Program in northern New Jersey. She teaches dedicated classes of MLLs ranging from emergent bilingual to advanced. As such, she employs innovative ESL strategies and theories with creative methodologies to assist her students in making meaningful and successful language gains. Her mandate – to create a classroom setting that is rigorous, inclusive, welcoming, and inviting while providing students with a soft place to land. She is a graduate of Monmouth University with a MA in Education along with certifications in ESL, Social Studies, and Elementary Education.

The author – Dr. Chiu-Yin (Cathy) Wong is Associate Professor of Curriculum and Instruction at Monmouth University in New Jersey, USA where she teaches courses in ESL methods, Bilingual Education, and Applied Linguistics. She is also the director for the Master of Education/TESOL program. Dr. Wong’s students often comment that she is a talented instructor and that her courses are rich with content and learning opportunities. Her research focuses on effective pedagogies and second language teachers’ perspectives as they support students’ learning in various aspects. Currently, her research interests lie primarily in the area of teachers’ learning and implementation of pedagogical translanguaging in ESL as well as Chinese immersion settings. Her recent work appears in e.g., Applied Linguistics, ELT Journal, and International Journal of Inclusive Education.

Curriculum-Thinking around the 2020 WIDA Standards Framework

By Maggie Churchill and Hana Prashker

After nearly two years of looking and learning with NJTESOL/NJBE about the 2020 WIDA Standards Framework, a question still looms in our heads: How do we implement the Framework in our classrooms? One of the best resources we have is something teachers see every year at this time: ACCESS for ELLs 2.0. Teachers of multilingual learners (MLs) are already familiar with the format and expectations of the test. Even the content is already familiar to us- the big picture, Nina, the test booklets. At this time of year, teachers of MLs begin the task of preparation, which includes completing sample items with students to provide authentic practice prior to actual testing. It is those released test questions that we should use as models as we begin to consider our own curriculum-planning with the 2020 WIDA Standards Framework.

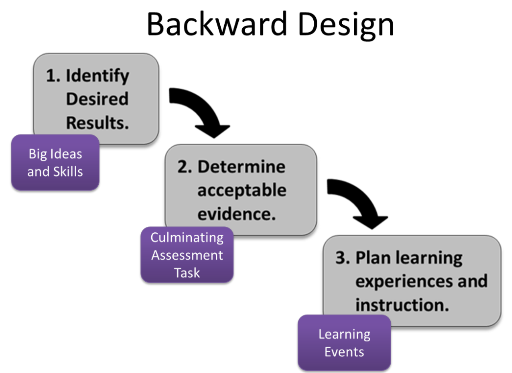

The released ACCESS Test Practice and Sample Items are available in both paper and digital formats from the WIDA website. These simulations are instructive in the curriculum-planning process known as “Understanding by Design”, also referred to as “Backwards Design”. For a comprehensive primer, try Bowen’s guide. By examining the anticipated outcomes first, we put student progress and growth at the center of our units, keeping intentional the demonstration of language expectations and communicative competence.

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

Step 1: Look at the released ACCESS items to identify the results. THINK: What do students have to do?

Step 2: What kind of evidence is needed? What’s required in the final task?

Step 3: How will students get there? What explicit instruction will you plan?

It is necessary to begin with the end in mind: What do students have to do? A close look at the end task on the ACCESS sample items reveals both the Key Language Use and the performance task expectations for students. The following chart provides a breakdown of the released ACCESS items by grade-level cluster and tier. It is important to note that future ACCESS tests may showcase other Key Language Uses, and are not limited to only those listed here:

ACCESS for ELLs Released Sample Items (subject to change each year)

(Tier B/C is in blue to show contrast.)

p. 118, 2020 WIDA Standards Framework

When we examine the end tasks on the ACCESS for ELLs 2.0 test, we can see the big ideas as they relate to WIDA’s Key Language Uses: Narrate, inform, explain, and argue. The next step would be to examine the grade-level cluster in the 2020 Framework in order to determine what acceptable evidence looks like– READ: Language Expectations. So, if a 4th grade student is asked to explain how to solve a math problem on the ACCESS test, then the Framework guides us to the acceptable evidence as listed in the Language Expectations:

The Language Expectations in the 2020 WIDA Framework make intentional the anticipated outcomes for students, and help teachers design instruction that focuses on these expectations. Within each grade-level cluster and Key Language Use and specific Language Features that facilitate these learning events and outcomes for students. The identified Language Features might be considered performance-driven, since these are essential in the expressive mode of communication. When explaining the solution to that math problem, the 4th grade student should focus on the bulleted features in order to provide the actual explanation. These Language Features, also listed on p. 118, would include content-specific vocabulary, relational verbs, generalized nouns, language that examines choices made, first or third person stance, and comparative forms:

Language Functions and Sample Language Features

Introduce concept or entity through…

- Mathematical terms and phrases to describe concept, process, or purpose (the angles within a circle can be measured with a protractor like this)

- Relating verbs (belong to, are part of, be, have) to define or describe concept

Share solution with others through…

- Generalized nouns to add precision to discussion(conversion, measurement, volume)

- Language choices to reflect on completed and on-going process (we should have done this, we might be able to, what if we try)

- First person (I, we) to describe approach; third person to describe approach with neutral stance of authority

- Observational (notice, it appears, looks like) and comparative language (different from, similar to, the same) to share results (We notice our process was different, but we have the same solution.)

Teacher-designed learning events will need to include specific instruction in the identified Language Features, with authentic practice built-in to optimize student utilization. These are the words, terms, and examples of language that students will need to use during language production- both spoken and written in the end tasks of the ACCESS test. They will need to be prevalent in our units and lessons as we begin to plan for instruction.

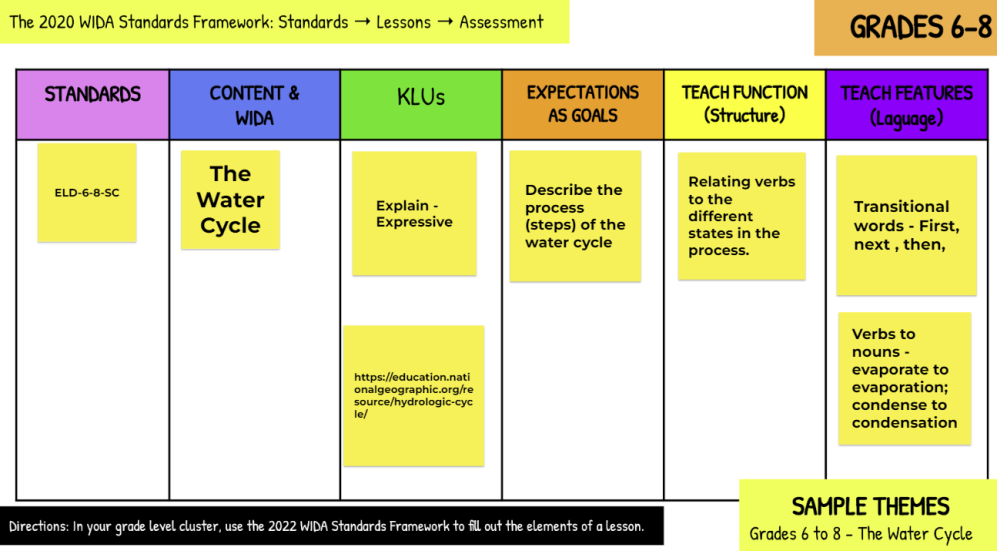

Now, what remains is the best part: Design learning experiences that will lead to student success! To this end, NJTESOL/NJBE has designed a Unit Sketch tool to facilitate the curriculum-thinking process. A completed sample, created by participants of the 2021-22 NJTESOL/NJBE PLC: Looking and Learning about the 2020 WIDA Standards Framework is included below.

Credit: Maria Cecilia Vila Chave

While in this article, we are focusing on curriculum developed from ACCESS testing items, the 2020 WIDA Standards Framework and “Backward Design” should be used for developing curriculum for MLs related to the grade-level content-area curricula. The outcomes from content-area curricula can be the Step 1 (see page 1) in the “Backward Design” process. For Step 2, think: What do students need to succeed to complete the final task in that content-area unit? Finally, as teachers of multilingual learners, consider: What do we need to directly teach students to achieve the academic and linguistic goals of the content-area unit? Using these explicit steps is a perfect opportunity for teachers of MLs and content-area teachers to collaborate as they begin thinking about and writing inclusive curricula that is intentional in its design.

The Authors –

Maggie Churchill is the current Past President of NJTESOL/NJBE and chair of the professional development committee, which hosted a two-year PLC that facilitated looking and learning around the 2020 WIDA Standards Framework. She is a regular presenter at the national WIDA Conference, a long-time presenter at the NJTESOL/NJBE Spring Conference, and a former member of the WIDA National LEA Advisory Committee and NJDOE Bilingual Advisory Committee. Maggie authored the 7th grade ELL Exemplar Unit of the NJDOE Model Curriculum. She teaches middle school ESL language arts and teacher preparation courses in ESL/bilingual certification at William Paterson University.

Hana Prashker teaches multi-level ESL classes and co-teaches content area classes in grades 6-12 in Hasbrouck Heights, NJ. She has been teaching ELLs and mentoring teachers for over 30 years. Her teaching certifications include ESL, K-8, and Language Arts. She has also successfully trained classroom teachers in Sheltered English Instruction strategies. Hana serves on the NJTESOL/NJBE executive board and is a member of the Professional Development, Advocacy and Parent Expo committees.

How Does Sara Think?

By Tina Kern

Sara was guided to the correct answer by highlighting phrases and sentences in the selection and yet still she struggled to find the answer to one of the higher-level questions that accompanied her reading. She didn’t have any difficulty with the “right there” questions – the ones whose answers could be found easily in the selection. On the other hand, she couldn’t manipulate the information to extract information that wasn’t explicitly in the text. She finally elicited the answer.

Sara was guided to the correct answer by highlighting phrases and sentences in the selection and yet still she struggled to find the answer to one of the higher-level questions that accompanied her reading. She didn’t have any difficulty with the “right there” questions – the ones whose answers could be found easily in the selection. On the other hand, she couldn’t manipulate the information to extract information that wasn’t explicitly in the text. She finally elicited the answer.

“Great! Now let’s discuss how you found the answer,” I said in my best excited teacher voice.

“No, thank you,” she replied quickly. “I have the answer, right?” When I continued, hoping she would be curious to know why it was correct, she reiterated, “It’s the right answer, and that’s what counts.”

Why didn’t Sara care about knowing why the answer was correct? Though I had encountered this attitude before, returning to class after COVID, raised more concerns about the lack of progress in this new post-virtual era and the reasons for the inevitable gaps in education.

I noticed a growing apathy and lack of curiosity in the students. Did my colleagues find an attitude that centered on the results and correct answers, rather than the process that went into finding that answer? One of the math teachers echoed my concern when she expressed her consternation upon realizing that her students could pass a test, yet a mere two weeks later could not repeat the process that they should have learned from those lessons. They didn’t “learn” how to do the work; instead, they memorized how to achieve a passing grade. As a result, they couldn’t duplicate their passing scores again. Were they learning for the test, and not to integrate the information into their toolbox for future use?

Some teachers alluded to the “learning gap” and COVID. This, though, is not a new phenomenon. To be fair, when I stopped to evaluate my students and their progress, at times I had already noticed that some were apathetic beyond gaining points for their grades – before virtual learning. Yet this incredibly disturbing situation was becoming more prevalent.

A goal is to ignite a natural – or unnatural curiosity – in our students. The period of virtual learning during COVID made the task of self-discovery difficult, but when we returned to the classroom, I became more apprehensive about the learning processes of my students. With our data driven educational society, I wanted to observe, not the data culled from the summative assessment after a group of lessons, but the journey needed to successfully integrate the skills into the students’ toolboxes. If students learned the “how”, they could tackle more tasks successfully. As the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, founder of Taoism said: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach him how to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

Teachers do strive to give the students the tools to solve problems and search for answers. Unfortunately, though, after the virtual teaching that was experienced at the height of COVID, some of the focus has been on the loss of learning that standardized testing data has “uncovered”. That, in turn, has produced a frenetic race to increase the achievement scores. Does that necessarily mean that this will raise the learning curve and fill the gap? Will our students learn more, or produce better scores? They are not the same. They can be mutually exclusive.

In the race to raise scores, what message are we giving the students? Are they being taught (subconsciously) to focus on the final grade, or to savor the learning that goes into the lessons that help the students build upon the knowledge so they become independent learners? In the perfect storm of today’s educational community, the desire to have students reach a higher level is measured by the tests available to measure growth, mostly standardized tests, which our multilingual learners find difficult to negotiate. As a result, on these tests, our students tend to show limited growth, or at the least, not a true reflection of what they have learned. Instead, the focus seems to be on what they didn’t learn. This is a disheartening appraisal which administration might interpret as an indication of their classroom teaching

Looking at the educational atmosphere of today’s students means looking at many factors. Teachers are integrating social-emotional learning skills, conflict resolution, restorative strategies among other skills, into the everyday curriculum. On December 7, 2022, Education Week recently published an article, “Here’s How the Pandemic Changed School Discipline.” It highlights the “higher levels of trauma and anxiety, which leads to more conflicts and less impulse control.” In this environment of uncertainty, teachers are also tasked with pacing their lessons based upon a pre-pandemic curriculum, with the underlying tension created by the emphasis on final scores. Of course, teachers don’t just teach. We have to meet deadlines for various tasks, unrelated to classroom planning.

In the midst of everything and in the amount of time a teacher has to plan for the multitude of mandatory activities, how does an educator steal the time to add crucial lessons in learning that are beyond the curriculum? How do teachers channel the frenetic energy necessary to “catch up”, and at the same time ask students to stop and reflect upon their classwork and assessments? Foregoing this integral step in learning steals the opportunity to teach the students how to find the answers themselves, and to question the information and research they discover.

What can teachers do?

One idea is to modify our lessons to integrate different techniques that encourage our students to think critically. In this way, teachers can enrich the lessons without sacrificing the curriculum timeline. For example, QFT (Question Formulation Technique) questioning is the skill of having students generate their own questions, as the teacher’s role becomes the facilitator instead of the creator of the questions. According to the Right Question Institute, “the QFT builds the skill of asking questions, an essential — yet often overlooked — lifelong learning skill that allows people to think critically, feel greater power and self-efficacy, and become more confident…” (https://rightquestion.org/what-is-the-qft/ ) Students are taught to differentiate between closed and open-ended questions. As they delve further into question-making, they start to write closed questions for selections – in any content area. Then the skill is elevated to another level as students change these questions to open-ended ones. They discover the difference between the information gathered from a closed question, and contrast it with the depth of material they garner from an open-ended question. This self-discovery technique transfers to all areas and leads the student into critical thinking and other higher-level skills. It leads to more thinking, learning, and ultimately fuels student engagement.

The level of questions that are presented during a lesson naturally lead the students to HOT (Higher Order Thinking). Utilizing QAR (Question Answer Relationship) questions can help with differentiation as educators teach these various forms of questions to students. The “right there” questions are simply finding information in the text. When the student has to find information in two different places in the selection to completely answer a question, they are practicing “Think and Search” questions. “The Author and you” questions require the students to synthesize the information that the author supplies in the selection with their own knowledge. Opinion questions are called “On Your Own” questions in QAR. This technique leads the student from identifying facts to eventually formulating opinions based upon readings.

In some districts, platforms for reading and math are purchased to provide computer assisted learning in an effort to lead the student to more rigorous material. Most of the questions are closed, meaning there is only one answer. In this way the computer corrects the answers and the students are encouraged to complete each unit, receiving immediate positive feedback. Students see their progress as the correct answers accumulate. If the computer doesn’t explain the errors, though, in a way that the student can understand, will the student learn from the mistakes and be able to self-correct? How do we provide scaffolds to their thinking while they are utilizing these programs? How do we encourage students to ask “why” the answer is wrong?

Is there an underlying message that correct answers are valued, not the method that leads to the correct answers? The effectiveness of these computer programs is acknowledged, but teachers can elevate the substance of these platforms by having students evaluate their errors. If students can recreate the process they used to ascertain the answer, and be guided to correctly assess their errors, teachers then are leading them to be independent learners. The program then transcends the original purpose as teachers add another layer. Students are led to another level. Hopefully, with time, they shouldn’t be content with just supplying the correct answer. Educators want the students to ask “why” and “how”, not just plug in the “what”.

To combat the proliferation of students clicking through answers, and careless mistakes, teachers can institute some tactics to have students become more thoughtful learners, and slow down those that strive to finish the task almost before it begins! Begin to insist upon students justifying their answers with evidence. Have students correct their mistakes. If students don’t stop and reflect upon their incorrect answers, the teaching moment passes. Sometimes the process of finding the right answer becomes a more valuable lesson than having the correct answer, especially when elicited by chance.

Giving your students the gift of achieving higher level thinking skills is priceless, and will lead our multilingual learners on the pathway to success. Such additions to lessons, such as scaffolding strategies like “compare and contrast” with graphic organizers, enriching the engagement before lessons with short videos and online pictures so students can visualize and build background, can boost participation by allowing access to more content. Students also need to be led beyond the concrete to the abstract. Teaching abstract concepts are difficult. Students need to learn to look for patterns and search deeper. For example, in science students can think about results of experiments. In other classes, students can write and share stories. They can learn to elaborate upon simple answers, and supply evidence for their conclusions.

Many of our students need support and encouragement to think beyond the basics and ignite their curiosity. Teachers can provide a toolbox of realistic and practical strategies so, hopefully, many students are no longer content to answer indiscriminately, without thinking, just to complete an assignment. By leading students to higher order thinking through questioning and scaffolding instruction, teachers can instill skills to guide students and gift them the tools for lifelong learning and educational success.

References

Pendharkar, E. (2022, Dec 7). How the Pandemic Changed School Discipline. Education Week.

Right Question Institute. (2022, May 6). What is the QFT? https://rightquestion.org/what-is-the-qft/

The Author – Tina Kern is a Professor-in-Residence at William Paterson University, and provides professional development, coaching and mentoring at the New Roberto Clemente School in the Paterson School District. She is also an adjunct professor at WPU and Kean University in the Education and the English as a Second Language Departments. She has an MA in education, and NJ certifications in ESL, Bilingual Education, English, Spanish, and Elementary Education. Her experience includes mentoring teachers, being a Program Assistant and teaching ESL, and Bilingual Language Arts in the Morris School District for 30 years.

Science Education for All: Integrating Science Content Attainment and Language Development for ELLs

By Cecilia Vila

Introduction

To ensure success in the Science classroom, English Language Learners require content-area teachers to unlock their potential through differentiated instructional practices. Through an asset-based approach, teachers can access the funds of knowledge of all ELLs through the integration of content attainment and language development. Sheltered English Instruction (SEI) strategies are the first step in implementing an asset-based approach to teaching ELLs in the Science classroom. Through SEI, teachers make their instruction accessible to all students. However, to truly excel, ELLs require the integration of English academic language development and content instruction. However, with limited instructional time, rigorous Science standards, and standardized testing, how can Science teachers be expected to teach language as well as content?

The key to integrating language development and Science is shifting the instructional lens and focusing on the how rather than the what of our teaching. When Science educators approach content-teaching for ELLs through the lens of language learning, the Science classroom becomes an equitable and safe learning space where all students have access to the content.

Language development frameworks, such as WIDA’s ELD Standards Framework (June 2020 Edition), provide a roadmap to integrate Science and the academic language for science to ensure ELLs have equitable access to education. And they serve as the blueprint for collaboration between content area teachers and ELL teachers. Here are four steps that Science and ELL teachers can follow to make their science instruction accessible to ELLs:

Step 1: Aligning our Understandings

“(…) all teachers need to share responsibility for both engaging all learners in the core curriculum and developing essential language skills” (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2020). Thus, the ELL teacher and Science teacher must reflect and align their core beliefs to successfully design instruction that will engage all learners. The suggestion is that both teachers reflect upon and share their answers to the following questions to guide their discussion:

- Who are our English Language Learners?

- What can our English Language Learners do?

- How does Science instruction fit with the Second Language Acquisition process?

- Why should Science instruction include language development strategies?

Step 2: Using Data to Guide our Instruction

“The ability to harness student data to solve instructional challenges is becoming an increasingly critical skill in today’s complex learning environments” (Kaufman, 2023). The importance of data analysis cannot be overstated, but a common mistake is to look at data that is not necessarily relevant or appropriate to the academic development of English Language Learners. The data analysis process centers around four specific data sets:

- The student’s most recent English Language Proficiency scores obtained from a State-approved ELP assessment (For example, WIDA Model or ACCESS 2.0). In reviewing the scores, it is important to interpret them using guides such as WIDA’s Can Do Descriptors. It is also important to consider the student’s ELP individual scores in each of the language domains: Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing.

- The student’s educational background. While schools generally collect and review a student’s transcript or academic records when available, it is necessary for teachers to analyze what the student’s previous learning experiences have been. For instance, when reviewing a student’s educational background, it is imperative to understand whether that student is SLIFE (A student with limited or interrupted formal education), as their needs will differ from students who are not.

- Student input. Regardless of the age of the student, collecting student input serves two key purposes: to inform our instructional practice and to forge a strong learning partnership with the student. A common modality to collect student input is a beginning-of-the-year student survey collecting information such as learning styles, student interests beyond the classroom, current access to necessary resources, and necessary supports.

- Current learning goals. When integrating language development and content attainment, both teachers must collect and share pertinent data to their individual specialties and consider how they can design instruction that supports the achievement of all learning goals for each individual student.

Step 3: Building our ELL Toolkits

Whether you are an experienced teacher of content, or ELLs, it is important to remain committed to the continuous improvement of our practice. Thus, building our ELL toolkits through collaborative lesson planning and implementation of ELL strategies is a necessary step in designing equitable instruction.

- Before the lesson/ lesson planning: plan for the explicit integration of content and language instruction in the Science classroom by leveraging WIDA’s ELD Standards and Language Expectations for Science: “Multilingual learners will … “(University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2020). Once you have identified the expectations, use them to design content and language objectives.

- Beginning of the lesson: access your students’ prior knowledge. While the activation of their background knowledge takes place at the beginning of the lesson, it is important to plan it and structure the process beforehand:

- Identify key background knowledge needed for the lesson: key concepts, academic vocabulary, and prioritize.

- Leverage students’ existing background knowledge (tip: it does not need to be in English) through peer discussions, drawings, graphic organizers, and quick writes.

- Build the background knowledge your students need by using pictures, pre-teaching vocabulary, explaining concepts, and leveraging their home language.

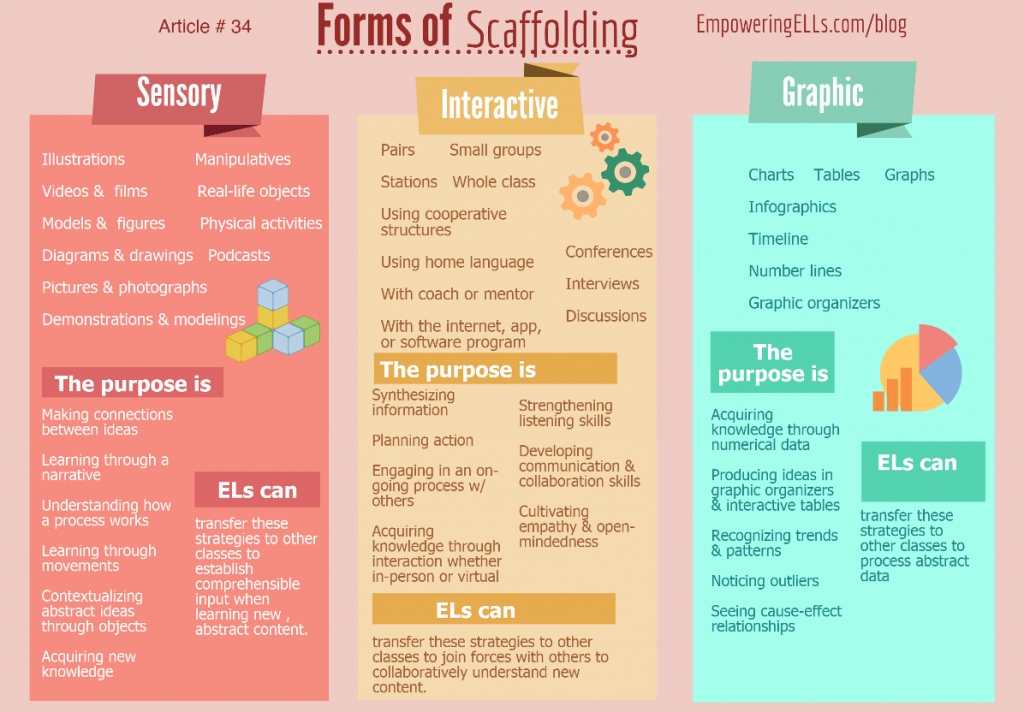

- During the lesson: make your input comprehensible to all students. Inaccessibility is often mistaken as rigor. Evaluate your resources to identify whether the material is accessible to your linguistically diverse students and utilize varied scaffolds.

Source: EmpoweringELLs.com/blog

- After the lesson: implement multiple modalities to assess content knowledge. Look at your current assessment practices and ask yourself: Am I assessing their learning in a way that allows them to show what they know regardless of their English Language Proficiency? If the answer is no, then update your assessments or design new ones that are varied and consider their linguistic diversity: entry and exit slips, interview assessments, self-assessments, oral presentations, and portfolio assessments.

Step 4: Seeking Further Understanding

Like the Scientific Method, a continued commitment to educational equity calls for seeking further understanding even when we believe we have mastered our practice. It is important to slow when implementing the four steps for language development and content attainment integration. So, what are the next steps?

- Ask: What is one thing from this article I can take back to my own classroom?

- Research: Who is somebody I can collaborate with to make it happen? What else do I need to learn about?

- Imagine: What are some ways in which I can implement it in my Science and ELL instruction? What additional tools will I need?

- Plan: How will my lesson plan(s) reflect this change? What do I currently do that works? What do I need to change?

- Create: What new tool, idea, or strategy will I be implementing?

- Test and Improve: How will I know if my new plan worked? How will I improve it and/ or try the next thing?

Conclusion

The goal of integrating language development and content attainment is not to add more to our already full educational plates. Rather, repurpose what is already on our plates to make it work more efficiently. Advocacy of educational equity can be done in many forms. Designing instruction that is accessible to all learners does not need to lower the rigor. Through the application of the four steps described in this article, educators will be able to enhance their instruction and support linguistically diverse learners. However, to implement this approach, administrators need to design opportunities for collaboration across curricular areas: co-planning time, co-teaching professional development, and instructional resources that support the acquisition of language through the content of science. And most importantly, leaders and teachers must shift their mindset from a departmentalized educational system to one that leverages the intersectionality between language and content.

References

Huynh, T. (2017, April 13). #34. Three types of scaffolding: There’s a scaffold for that. TanKHuynh. https://tankhuynh.com/scaffolding-instruction/

Kaufman, S. (2023). The data wise difference: Harnessing data to improve student outcomes. The Data Wise Difference: Harnessing Data to Improve Student Outcomes. Retrieved January 14, 2023, from https://datawise.gse.harvard.edu/data-wise-difference-harnessing-data-improve-student-outcomes

University of Wisconsin-Madison. (2020). WIDA Focus Bulletin – Collaboration. WIDA Focus Bulletin. Retrieved January 14, 2023, from

https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/WIDA-ELD-Standards-Framework-2020.pdf

The Author – Maria Cecilia Vila Chave is a Supervisor of ELL and Social Studies, at Ocean Township Schools, NJ. Her experience, both personal and professional, with Second Language Acquisition drives her commitment to advocacy and the implementation of best practices. As a multilingual student herself, she has first-hand experience of being an immigrant student in the U.S. And as a former Bilingual and ESL teacher, she has implemented best practices, in and outside of the classroom, to promote equitable access to education. As an executive board member of NJTESOL/NJBE, she continues to advocate for ML students, their families, and other educators.

Cooperative Teaching Notetaking Model – Shared Digital Notes

By Bryan Meadows

I co-teach in a high school biology class where EL students constitute around half of the 30 total students enrolled. During class time, I like to make teacher rounds in the classroom, checking in with ELL students individually at their seats. This is especially important during teacher-centered classroom activities such as mini-lectures and extended teacher explanations. However, with space limitations being what they are, I can become a disruption to surrounding students at each student stop. One might imagine attempting to make individual consultations in a crowded movie theater. So, I was looking for an alternative way to connect with individual EL students in real-time during classroom instruction – without becoming a disruption myself. One exciting classroom solution is shared digital notes. Essentially, the idea is for me to type listening notes during teacher-centered classroom activities and to make those notes available to students digitally in real-time in the classroom. What is innovative about this arrangement is that I am able to reach all students in their seats in real-time while I am in a single central location.

I co-teach in a high school biology class where EL students constitute around half of the 30 total students enrolled. During class time, I like to make teacher rounds in the classroom, checking in with ELL students individually at their seats. This is especially important during teacher-centered classroom activities such as mini-lectures and extended teacher explanations. However, with space limitations being what they are, I can become a disruption to surrounding students at each student stop. One might imagine attempting to make individual consultations in a crowded movie theater. So, I was looking for an alternative way to connect with individual EL students in real-time during classroom instruction – without becoming a disruption myself. One exciting classroom solution is shared digital notes. Essentially, the idea is for me to type listening notes during teacher-centered classroom activities and to make those notes available to students digitally in real-time in the classroom. What is innovative about this arrangement is that I am able to reach all students in their seats in real-time while I am in a single central location.

This is how it works. I open a single Google document at the beginning of a content unit (e.g., cell parts, macromolecules, etc.). I invite all ELL students in the class into the document with commentator privileges. In this classroom, all students have Chromebooks and use Google Classroom on a regular basis. Using their Chromebooks at their seats, students can follow the link they receive and enter the document. Once inside the document, they are able to see my notes as I type them. So, while I am typing notes in class, all students can see those notes as they are being created and in their respective seats in the classroom setting. With this technique, I can effectively bridge the need to connect with students during teacher lectures with the challenges of limited physical classroom space.

When taking notes, I am creating multiple language supports simultaneously. For example, I am highlighting for students key details from the teacher’s lecture by using the highlighter function in Google Docs. I am segmenting (i.e., chunking) content into sections by skipping lines and bolding sub-headings in the notes. I am also using the translate function to translate key terms and concepts into the multiple languages spoken in this classroom: Spanish, Portuguese, Ukrainian, and Arabic. I am also grabbing images to integrate into the notes where visuals can extend student comprehension. Importantly, I am also listening to and interpreting the teacher-centered lecture. This includes summarizing and paraphrasing, but also quoting the teacher’s language verbatim. The verbatim portions are valuable because they both reinforce EL student exposure to language expressions typical of the content areas (i.e., Zwiers’s notion of “mortar”) and provide essential elements for future sentence and paragraph frames that I create with the co-teacher. I continue with the same shared document during the individual unit of study. As such, the document remains on everyone’s google drive allowing all EL students to reference the notes as needed throughout the unit. For example, I observed multiple students using the shared notes recently as a reference tool to complete a unit-final project.

As I continue to refine the technique in my work with students in this setting, I look ahead to the possibility of increased student engagement in real-time with the shared document. For example, I envision students eventually being able to insert margin comments in real-time in class. Additionally, as the EL students become more acclimated to the shared document, there are strong opportunities for them to become co-authors – wherein the students and I take turns leading notes during teacher-centered activities allowing those in the secondary role to provide annotations and additional supports.

Reference

Zwiers, Jeff. (2014) Building Academic Language: Meeting Common Core Standards Across Disciplines, Grades 5–12, Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

The Author – Bryan Meadows is a secondary ESL teacher with South River Public Schools. He holds a PhD in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching and an MEd in Second Language Education. Over 25 years of service in the field of language education, Bryan has held a variety of roles that include classroom instructor, university faculty, academic researcher, teacher educator, instructional coach, and program director. His research appears in over 30 peer-reviewed publications. He holds NJDOE certifications for ESL (K-12), Elementary (K-6), and Supervisor.