NJ Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages

NJ Bilingual Educators

ARTICLES

Bilingual Elementary 1-8: Jack Meyers- Teacher-gram: Educators to Follow for Inspirational Words & Ideas on Instagram

Bilingual/ESL Middle School: Anel V. de Suriel- Home Language and Bilingual Assessments

Early Childhood: Jessica Perdomo-O’Hara- Supporting English Learners Through Collaboration

ESL Elementary: Andrea Pape- A Look at the Danielson/ELL Crosswalk

ESL Secondary: Hana Prashker- Sentence Expansion

Higher Education: Patricia George- College Matters

Parent and Community Action: Gabriela Colon- Back to School Night and More

Supervisors: Laura Arredondo- Ensuring Equity through Language Policies

Teacher Education: Lisa Rose Johnson- “Noticing” As a Tool for Reflection

Features: Fall 2019 Focusing on Equity

Bilingual Elementary Special Interest Group

Teacher-gram: Educators to Follow for Inspirational Words & Ideas on Instagram

By Jack Meyers

It’s another school year, and another brainy, quirky, diverse bunch of scholars are about to walk through your doors. Each young person carries with them a broad and deep range of knowledge, experiences, and, as a result, challenges. When I write “challenges,” I don’t necessarily mean behavioral concerns, although that certainly is a part of our students’ lives and also a part of our jobs. What I mean is that each student has been raised in a unique environment and has a unique disposition that, therefore, will cause the student to face academics in a distinct manner. Consequently, we, as education professionals, must rise to the occasion and meet all students where they are.

It’s another school year, and another brainy, quirky, diverse bunch of scholars are about to walk through your doors. Each young person carries with them a broad and deep range of knowledge, experiences, and, as a result, challenges. When I write “challenges,” I don’t necessarily mean behavioral concerns, although that certainly is a part of our students’ lives and also a part of our jobs. What I mean is that each student has been raised in a unique environment and has a unique disposition that, therefore, will cause the student to face academics in a distinct manner. Consequently, we, as education professionals, must rise to the occasion and meet all students where they are.

In my experience, this individualized instruction and management of young people quickly exhausts my creativity. To remedy the creative exhaustion, I began to reach out to other educators. First, I would ask those in my building and in my district, then around the state, the country, and even teachers I’ve met who educate young minds around the world. However, the most diverse and useful place I’ve found to derive creative solutions for the classroom has been Instagram. The following is my personal review of the top accounts of educators who are clearly leaders in education and provide wholesome, well-rounded, critical perspectives on a wide variety of topic. These topics include, classroom management, tackling gender and sexuality, culturally responsive instruction, environmental responsibility, and self-care. Best of all, you don’t have to have your own Instagram to follow any of these marvelously meaningful and knowledgeable folks!

First up to bat is @paul_emerich, an educator and author whose blog constantly reminds me to take a step back, reflect, and critique widely held beliefs about classrooms, teachers, and education as a whole. One of my favorite thought pieces by Paul is his aptly titled “3 Reasons Your Kids Hate Writing.” In this blog post, he breaks down the roots of writer’s block in kids, namely calling in teachers to reconcile with the reality that kids learn to dislike writing, and that creativity is supported by students feeling their ideas are valued and worthy of writing about.

Next on my list of inspiring educators is the GLSEN (Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network) 2019 Educator of the Year who can be found on Instagram at @teachingoutsidethebinary. Mx. Schwarz (n.b.: Mx. is a gender-neutral honorific similar to Mr. or Mrs. or Ms. and is pronounced “mix”) uses their platform to elevate the conversation about gender in school, and their compassionate approach to critiquing bias is refreshing. In addition, if you are looking for a comprehensive list of resources for being a culturally responsive teacher, Mx. Schwarz is your educator!

Last, and most certainly not least, is the magical Kindergarten and 1st Grade ELL Teacher, @msk1ell. This educator has helped me challenge my own biases and opens dialogue about critiquing cultural prejudice in classrooms and in teacher’s instruction. What I appreciate and enjoy most about this educator is her ability to tackle big-ticket issues with grace and eloquence. If you’re looking for some thought-provoking content on diverse literature and diverse narratives in the classroom, @msk1ell is the educator for you!

In brief, get out there on social media and even in real-time and explore the possibilities that an open dialogue can bring to your teaching practice and your educational philosophy.

Jack Meyers is a 3rd Grade Bilingual Teacher, Franklin Twp (Somerset County). He also serves as the Bilingual Elementary SIG Representative.

ESL Middle School Special Interest Group

Home Language and Bilingual Assessments

By Anel V. Suriel

The onset of the academic year means the start of assessments. Many times in the beginning of the year, assessments are used to plan learning activities, to gauge learning, and to determine strengths and needs. However, quite often, the assessment instruments teachers use to obtain this beginning of the year data are monolingual and aim to evaluate student readiness in one language: English. For emerging bilinguals, this may not align with classroom practices that use a variety of languages for learning.

The onset of the academic year means the start of assessments. Many times in the beginning of the year, assessments are used to plan learning activities, to gauge learning, and to determine strengths and needs. However, quite often, the assessment instruments teachers use to obtain this beginning of the year data are monolingual and aim to evaluate student readiness in one language: English. For emerging bilinguals, this may not align with classroom practices that use a variety of languages for learning.

The best assessments for emergent bilinguals are those which see student’s home language use from a lens of promise or a position of strength (Mahoney, 2017). However, few scripted assessment programs come equipped with the evaluation tools necessary for assessing multiple language use within the one testing tool. This results in using multiple assessments in order to gauge home language performance against target language performance. Such creates issues of impracticality– particularly when teachers are required to evaluate student growth at multiple points during the academic year.

To evaluate the emergent bilingual learner, the conscientious language teacher will use an English language assessment as one of several and multiple measures. Amongst these are instruments that inform home language abilities. But, can the assessment process be streamlined and made more practical, more reliable, and more authentic? For this to take place, there must be room for flexible language use within one test tool. Namely, for an accurate and authentic measure of learning, assessments should allow for home and target language within the same instrument.

Issues of impracticality do not imply that monolingual assessments are invalid or unreliable for evaluating emergent bilingual students. Nor does it mean that the only way to accurately assess emergent bilinguals requires the use of two separate or side by side instruments. Instead, for emergent bilingual students, a more practical and accurate test may be one that allows students to flexibly choose between both home and target languages within the parameters of one assessment tool.

To clarify, the language teacher must evaluate student performance on assessment tasks as two-fold: performance of content understandings and emerging target language use—even when the two are inextricably linked. Together, these will provide a holistic view of the emergent bilingual learner while ensuring equity in assessment practice.

Home language use provides a holistic view of learning. Valid assessments for emergent bilingual students must differentiate between language proficiency and content understandings. In content areas in which language is intrinsically linked, i.e. reading comprehension and miscue analysis, student performance will be inextricably correlated to the interaction between home and target languages (Ascenzi-Moreno, 2018). Emergent bilinguals use a full range of language knowledge and skills to make meaning of content. Therefore, an assessment that allows the use of an entire linguistic repertoire provides a whole picture of content learning, while informing the developing language abilities that have emerged when language and content intersect.

For such an assessment to be equitable and accurate, it must be built on the premise that home language use is a strength. Home language use on a target language assessment may be a method of communicating conceptual understandings without the encumbrance of still emerging acquisition of target language constructs. Furthermore, errors in language uses can be analyzed for misconceptions in content understanding or language acquisition without resulting punitive effects on the student.

Therefore, the use of home language in assessment is equitable practice. To deny emergent bilingual learners access to his/ her home language is for force him/her to function with a finite portion of his/ her language skills (García, O., et al, 2016). This constraint, especially when comparing performance to classroom and grade-level peers with full access to their entire linguistic repertoire is a social injustice (García, O., et al, 2016). To deny a student use of the full range of his/ her linguistic ability undeniably results in invalid assessment data. The use of such inaccurate data can have far-reaching, negative consequences, i.e. involvement in repeated classroom remediation tasks instead of higher-order extension activities and/or referrals to intervention programs and classes in place of desired electives (Gottlieb, 2016). The use and acceptance of home language practices ensure that emergent bilingual student abilities are measured accurately alongside classroom and grade-level peers.

The essential element to this holistic and equitable practice lies in the language educator. The ability to see language development alongside content learning is a highly specialized skill that resides in the language specialist. As such, the language teacher is a vital component of equitable practice and must have a clear voice in assessment creation, assessment use, and assessment evaluation (Ascenzi-Moreno, 2018). In this role, the language teacher also becomes an advocate—one that forces stake-holders and decision-makers to keep the needs of all learners in mind.

Works Referenced and Recommended Reading for Further Investigation:

García, O., Johnson, S.J., & Seltzer, K. (2016). The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning. PA: Caslon Publishing

Gottlieb, M (2016). Assessing English Language Learners: Bridges to Educational Equity, Connecting Academic Language Proficiency to Student Achievement. 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin

Mahoney, K. (2017). The Assessment of Emergent Bilinguals: Supporting English Language Learners. NY: Multilingual Matters.

Moreno, Laura. Translanguaging and Responsive Assessment Adaptations: Emergent Bilingual Readers through the Lens of Possibility. (Report). Language Arts. 2018;95(6):355-369.

Anel V. Suriel is the NJTESOL/ NJBE Bilingual ESL Middle School 6-8 SIG Representative. She is the Bilingual Literacy Instructor for grades 6-8 at Franklin Township School District and a Doctoral Teaching Assistant at the Rutgers Graduate School of Education.

Early Childhood Special Interest Group

Supporting English Learners Through Collaboration

By Jessica Perdomo-O’Hara

Hi all! Have you heard the saying, “it takes a village to raise a child?” If we were to say the same in one word, it could be collaboration. What a beautiful word when done right! And how critical it is for the success of our English Learners. This is especially true at the beginning of the school year, when our students are starting in a new classroom, with a new teacher. These are some things we can do to help general education teachers teach our students:

Share Information – Many of us as ESL and bilingual teachers have the opportunity to teach the same students for more than one year and collect powerful information that can be key in helping classroom teachers meet English Learners where they are at to move them forward. This is very important, especially at the beginning of the year.

Some information that can really help your English Learner’s teacher is his or her background information. Do you know that one of your students lives with her grandmother and left his parents in his native country? Maybe you know that a student is 8 years old but only completed Kindergarten because her family was forced to continually move because of violence. Perhaps you learned that the student was in a gifted and talented class at a prior school. This is critical information that is so much information for the classroom teacher when planning and preparing learning experiences for her students.

What you have learned from teaching your students in prior school years is also very beneficial.

Sharing information about students’ learning styles, interests, scaffolding strategies that have worked in the past, strengths, and weaknesses, will save the general education teacher time and will give English Learners exposure to successful learning experiences earlier in the year.

If you teach in small groups every day, you will probably get to know English Learners faster than the classroom teacher. Do not be shy to share what you discover, or proposing to work on a specific goal together. You may identify academic needs, successful scaffoldings, or things that did not work. This information will help the classroom teacher focus her instruction.

Lastly, share information about things English Learners might struggle with because of their native language: writing direction, different alphabet, phonetic confusion due to similar sounds assigned to different phonemes.

Share Strategies – As experts in teaching English Learners, all the teaching strategies that we use on a daily basis to help our students acquire language and move forward academically are invaluable tools for the general education teacher who might not be familiar with them. With our help, our strategies can be easily integrated into the general education class to make content accessible to our students. A great start can be sharing what students can do in the classroom based on students’ level of language proficiency (WIDA ACCESS score). I personally like sharing this information using WIDA’s report for parents, which is enclosed in each student’s score report. It uses friendly, easy to understand language.

To me, an easy way to explain to the classroom teacher what language a student can understand is to say “The same level of language that the student speaks, she can understand”.

Show, Not Tell – Lastly, for now, I invite you to show, and not just tell. Take some time to model ESL strategies for classroom teachers. Perhaps, use an “I do, we do, you do, approach”. Offer to teach a class, and/or keep an open door for teachers to visit and observe your teaching. Offer your help in articulation and planning meetings, so you can provide information about language supports and scaffolding components.

Colleagues, collaborating with general education teachers is a meaningful and purposeful way to advocate for our English Learners. Having experts by their side might help classroom teachers feel more confident as they plan, prepare, and create learning experiences for our English Learners. Let’s make that village that our students need to be successful.

Jessica Perdomo-O’Hara is the NJTESOL/NJBE Bilingual/ESL Early Childhood Representative and a Pre-K ESL Teacher in the North Plainfield Public Schools.

ESL Elementary Special Interest Group

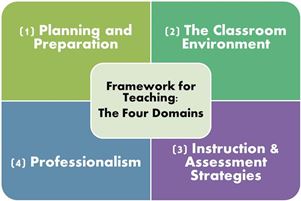

A Look at the Danielson/ELL Crosswalk

By Angela Pape

At last, an evaluation tool that recognizes the distinct qualities of English as a Second Language (ESL) instruction! Published by the New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE), the Danielson/ELL Crosswalk serves as a supporting document to the widely used observation instrument known as the Danielson Framework for Teaching. The document offers educators insight into recommended instructional practices geared towards meeting the needs of English Language Learners (ELLs). Evidence of these practices during a classroom observation may result in “effective” and “highly effective” scores.

At last, an evaluation tool that recognizes the distinct qualities of English as a Second Language (ESL) instruction! Published by the New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE), the Danielson/ELL Crosswalk serves as a supporting document to the widely used observation instrument known as the Danielson Framework for Teaching. The document offers educators insight into recommended instructional practices geared towards meeting the needs of English Language Learners (ELLs). Evidence of these practices during a classroom observation may result in “effective” and “highly effective” scores.

Focusing primarily on Danielson’s Domain One: Planning and Preparation as well as Domain Three: Instruction, the NJDOE developed the document with clear intentions for both administrators and educators alike. While not meant to replace the current system of evaluation, it equips administrators with definitive “look-fors” when observing the instruction of ELLs. This may come as no surprise for ESL supervisors, but for those administrators less familiar with the intricate craft behind ESL instruction, the Danielson/ELL Crosswalk sheds light on exemplary teaching and learning through the lens of language acquisition. And for teachers, this crosswalk creates a unique opportunity to engage in professional discussions pertaining to best practices for ELLs.

Still, one of the greatest victories included in this thirteen-page document exists as a footnote acknowledging the unique challenges ESL teachers face. With specific regard for Danielson’s focus on “student driven/student initiated” learning, an area which has previously led to less than desirable evaluation scores, this final disclaimer advises administrators to consider the impact students’ English Language Proficiency (ELP) levels have on their ability to engage in whole class discussions. Expounding on this point, the document states, “students at ELP levels 1 & 2, who are in the developmental process of acquiring a new language, by definition and description, are not able to initiate discussion or manage student-driven activities” (NJDOE, n.d., p.12-13).

The footnote further explains that students at the early stages of English proficiency often lack the language skills needed to participate in student-led discussions and describes the process through which students begin to develop increasingly more complex linguistic abilities. For example, students at ELP level three and above may be expected to independently produce complete sentences, however, this may not be realistic for students at levels one and two. Therefore, teachers who establish safe environments in which emergent ELLs do not feel overwhelming pressure to participate in oral discussions may actually meet the criteria needed to receive highly effective scores, as defined by the crosswalk. Most importantly, the Danielson/ELL Crosswalk encourages administrators to inquire about students’ ELP levels and the implications they may have on what quality instruction looks like for teachers of ELLs.

References (n.d.). New Jersey Department of Education. Danielson/ELL Crosswalk. Retrieved from https://www.nj.gov/education/bilingual/resources/Danielson.pdf (n.d.).

The Framework. Retrieved from https://danielsongroup.org/framework (n.d).

Charlotte Danielson Framework for Teaching. Retrieved from http://www.trentonk12.org/Downloads/Charlotte%20Danielsons%20Framework%20for%20Teaching.pdf

Angela Pape is the Elementary ESL SIG Representative and a 4th Grade ESL Teacher in Franklin Township in Somerset County.

ESL Secondary Special Interest Group

Teacher Tool: Sentence Expansion

By Hana Prashker

While spending the summer at home, I had plenty of time to read books. The one professional book I read was The Writing Revolution: A Guide to Advancing Thinking Through Writing in All Subjects and Grades, by Judith C. Hochman and Natalie Wexler (ISBN: 978-1-119-36491-7). This insightful book provided a few useful tips that I will highlight in this article.

This book is a must-read for teachers who teach in both secondary ESL and secondary content-area classrooms.The Writing Revolution (Hochman and Wexler, 2017) has ideas and activities that can easily be included as part of daily classroom instruction. This writing curriculum was initially created to help special education students and was later expanded for use with all students in academically low-performing districts. Three activities that I will highlight below can be used in any subject area, but teachers in high school English and History may initially appreciate them more.

One activity that was included in the book describes how to use sentence stems. Students were provided the same sentence stem to begin three sentences, then were asked to change the conjunction. Appropriately completing sentence stems can help show content-area teachers that ELLs (English Language Learners) understand the content being taught. Initially, this would be completed as a whole class activity, then in small groups or pairs. Possibly, students can complete this individually later in the school year. These completed sentence stems can be used as topic sentences for single paragraphs or body paragraphs in an essay. Here is an example from the book (p.43):

Abraham Lincoln was a great president because he kept the North united during the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln was a great president, but many Americans did not like him while he was alive. Abraham Lincoln was a great president so more books have been written about him than any other American Leader.

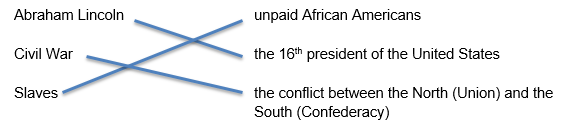

A second activity is helpful when teaching ELLs how to expand their ability to write topic sentences is teaching students how to to use appositives. An appositive is a second noun, phrase, or clause placed next to the noun it is explaining. To help students use appositives, teachers can have students complete a matching exercise with the noun in one column and the appositive in the second column. Another way to differentiate would be to give 3 sentences with a blank for the appositive (can be given) to be filled in.

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was assassinated in April 1865. The Civil War, the conflict between the North (Union) and the South (Confederacy), took place from 1861 to 1865. White plantation owners needed slaves, unpaid African Americans, to plant and harvest their crops.

The third activity that helps ELLs improve their writing is to have students create sentences and show comprehension is using the 5 WH-questions to expand sentences. Students may not answer all five questions. You may want to begin with only 3 of the questions words. The authors suggest using the “when” at the beginning of the sentence to teach sentence variety. The topic for this example is Abraham Lincoln. Who: Abraham Lincoln What: 16th president When: 1861-1865, Civil War Where: the United States Why: people in the North were against slavery

Final sentence: During the Civil War from 1861 to 1865, Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States because Northerners were also against slavery.

These three activities can help ELLs expand their sentences, create topic sentences more easily and show comprehension.

References

Conjunctions. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://partofspeech.org/conjunction/

Hochman, Judith C., and Natalie Wexler. The Writing Revolution. Jossey-Bass, 2017. Simmons, R. L. (n.d.).

The Appositive. Retrieved from https://www.chompchomp.com/terms/appositive.htm

Hana Prashker is the ESL Secondary SIG Representative and Bergen County Chair and a Hasbrouck Heights ELL Teacher.

Higher Education Special Interest Group

College Matters

By Patricia George, Ed.D.

This fall, across the state of New Jersey, higher education campuses will welcome an increasingly diverse student population for another semester. English language learners (ELLs) who enter postsecondary institutions come from different cultural backgrounds, educational and economic circumstances, and linguistic abilities. However, they each face the challenge of developing precise language proficiency while simultaneously learning rigorous academic content in English. Supporting ELLs in a demanding higher ed environment requires instruction that is personalized to their proficiency level, emphasizes culture, and prepares them for success in their academic discipline (Bergey, R., Movit, M., Simpson Baird, A., and Faria, A, 2018).

We all know that meeting the needs of ELs has its challenges. Nevertheless, when I have taken the time to learn who my students are as individuals, my classrooms have become communities with a shared mission. While a syllabus explains the objectives of the course to students, I also create a simple survey that provides me with invaluable information about my ESL students. Their responses help me connect with them on a personal level. In addition to learning what drives my ESL students’ academic pursuits, the survey provides me with a window to their home environment, language and cultural background, prior education, literacy level, and interests outside of academics. In my experience, conversations about expectations and U.S. education norms are more effective in an environment of mutual respect has been established through personal connections.

Knowing more about the ESL students’ interests also helps me design lessons and incorporate print and media sources that appeal to them personally. The higher ed pace of learning is demanding, and much needs to be covered in a 12-week semester. Even with constant feedback and assessment, ESL students do not often see their own progress as I do. Portfolios demonstrate remarkable growth and give ESL students a sense of accomplishment. Portfolios also highlight areas in need of improvement. I start the semester by having students create a free digital portfolio via Google Sites. Though initially time-consuming to develop, once the account is created, students can easily upload documents throughout the semester. By giving me access to their portfolio, I’m able to make suggestions and leave comments specific to the student’s concerns. I’ve found that higher ed ESL students at all proficiency levels appreciate knowing (and seeing concrete evidence) that they are making gains throughout the semester. The Google Sites portfolio is one tool that helps to serve that purpose.

Note: For step-by-step instructions on how to get students started, there are several YouTube videos that will walk you through the process. Here is a link to a source I’ve used in the past.

Source

Bergey, R., Movit, M., Simpson Baird, A., and Faria, A. (2018). Serving English Language Learners in Higher Education: Unlocking the Potential. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research. Retrieved from https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Serving-English-Language-Learners-in-Higher-Education-2018.pdf

Patricia George, Ed.D., is the Higher Education Special Interest Group Representative. She works at Rutgers University and Kean University

Parent and Community Special Interest Group

Family Engagement: Back to School Night and MORE

By Gabriela Colon

I hope that everyone had a restful summer and a smooth start to the 2019-2020 school year! This is such an exciting time of the year. It is when we prepare our minds and classrooms for the best year yet! This is the time of year, when Target has the best teaching “must-haves” in their bargain bins, and when we welcome our new students and their families to class. The fall is also when most schools have some of their most significant events, including back-to-school night and fall conferences. For many of our families (especially the newest ones), these events can be super exciting, but some families may also find them to be overwhelming. As ESL/Bilingual resources, we often serve as liaisons between schools and families and brokers of language and culture. If this is your first year or if you are looking for some new ways to support families, I have highlighted a few suggestions to keep families engaged beyond Back to School Night and consistently throughout the year.

1. Promote clear communication: There are many papers, forms, and opportunities for communication that exist between school and home. While we know that there is a legal obligation to have certain documents translated into the native language of families, what do we do about everything else? And while there are undoubtedly popular languages in New Jersey, there are many languages that are not dominant in the district and often left out. Those families may need you the most. Even if you don’t speak every language in the world, you are the language expert! You have sheltered instruction strategies, language scaffolds, and a handy tool-belt full of tricks. You can share what you know with colleagues and administrators to create a more supportive school culture for families who don’t speak English.

2. Facilitate opportunities: Educators are excellent facilitators, as we set up our students for success each day. Facilitating opportunities for families may involve personally inviting them to PTA/PTO meetings, sharing volunteer opportunities in the classroom/school, forwarding them the email about English classes at the library, and many other seemingly small moments that make a massive difference to the person on the other end. While I was involved in a family literacy project at Rutgers, a need for parents to understand how to organize playdates came up. That has stayed with me all this time, and now that I am a parent, I see how multi-faceted the school experience can be for parents. We want our children to do well and learn a lot while also making friends and feeling that they belong. We want them to be happy!

3. Empower: There are many ways to empower our families. When we facilitate communication and opportunities, we help parents to discover the power that their voice and presence have in our schools and in their child’s education. We know there is so much value in their experiences, language, and culture. By asking parents questions and seeking input, we can show families that there is a space for them and their ideas. Each district is very different and has access to various resources. Knowing about local resources and encouraging parents to reach out to each other can make a significant difference to a parent who is unfamiliar with the new school system.

4. Advocate: Please see 1, 2, and 3. We hope that all of our families experience clear communication, have many opportunities to become involved, feel empowered, and so much more so that they can support our students. When we are included in conversations that our families are not, it is so vital that we serve as a voice for their wants and needs. As with most relationships, we must make the most of each opportunity to build trust and realize shared goals. Family engagement can be a long process, but this is a great time to start!

Resources: https://www.state.nj.us/education/bilingual/resources/Title3ParentInvolvement.pdf https://www.nj.gov/education/bilingual/parents/family.htm https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/ABCs-Family-Engagement.pdf

Gabriela Colon is the Parent Involvement and Community Action SIG Representative and an ESL Teacher at the North Plainfield Schools.

Supervisors Special Interest Group

Ensuring Equity through Language Policies

By Laura Arredondo

Efforts to ensure equity for ELLs (and all students) have resulted in a proliferation of rules for all facets of instruction. These guidelines are part of a continuum resulting from the thinking that inspired Brown vs. Board of Education, Title IV of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Lau v Nichols of 1974, the curriculum movement, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 and the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015. Despite the guidelines, teachers continue to make individual instructional decisions, for better or worse. For teachers of ELLs, this frequently includes deciding how and when to use students’ first language in instruction.

Certainly, specialists of ELL programs understand the principle behind Lau (and all the above mentioned legislation). Students learning English are not to be denied access to a meaningful education, which means that they need to comprehend classroom instruction and materials. Furthermore, it is the responsibility of school districts to provide this access. Naturally, classroom instructional language will differ based on the ELL program (part-time bilingual, high intensity ESL, etc.). Nevertheless, we know that ELLs are not to wait to acquire English before they are provided with meaningful instruction in content areas.

Why do the ‘English-only’ and ‘sink or swim’ ideas still exist? I ask myself these questions as my colleagues and I continue to endeavor to deconstruct persistent misconceptions based on assimilationism and the perception of the native language as a barrier to learning (Moje, Ciechanowski, Kramer, Ellis, Carrillo & Collazo, 2004; Garcia, 2017). These include the idea that one’s brain can only contain one language…the more Spanish (Chinese, Tagalog, Portuguese, etc.) the student knows, the less room there is for English. Also, there is the commonly reported anecdotal evidence such as “My grandparents came here and learned English with no help, unlike these people who do not want to learn English and blend in?”, which precludes a perspective of students as capable and of native languages as resources (Callahan, 2013).

I’d like to suggest here that there is an additional factor, an important consideration that impedes our message. Confusion about language use in the classroom is also a result of inconsistent macro-policies, those policies at the state and federal level that conflict with each other, or with those of school districts. For example, while many states, including NJ, promote native language instruction in state code, recertifications of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act specified that programs for English language learners be focused on English acquisition, which contributed to a climate that repressed the use of native languages in classrooms (Kim, 2015). The movement which decentralizes schools in large districts also inhibits understanding. Some research indicates that local administrators are more influential than teachers in determining language use in classrooms (Johnson & Johnson, 2014; Menken & Solorza, 2015). This is a fact that should concern all of us, especially if the administrators subscribe to disproven ideas about language and classroom learning.

New research in translanguaging underlines the that multilingual abilities are important resources for students for the acquisition of transferable literacy skills, and maintains that limiting students’ use of the first language obstructs the learning process (Canagarajah, 2015; Garcia, 2017). Furthermore, in content area classes, the acquisition of content concepts is at least as important as the acquisition of English content academic vocabulary. Allowing students to negotiate meaning using their complete linguistic repertoires, providing supports such as dictionaries and translators, and permitting students of entering English proficiency to express responses in their first language, makes sense and reflects best practice.

It is of utmost importance for district ELL supervisors, specialists and other knowledgeable team members to work together to create a coherent language policy which specifies the language(s) of instruction to be used by teachers in each classroom setting, provides guidelines for content and language objectives, and suggests appropriate methods of eliciting student language. The lack of clear policies at the local levels as well as teachers’ reluctance to discuss their language use in the classroom creates inconsistencies and can be detrimental to learning for ELLs (Colón & Heineke, 2015).

References

Brown V. Board Of Education. History.com Editors – https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka.Retrieved on September 12, 2019.

Callahan, R. M. (2013). The English learner dropout dilemma: Multiple risks and multipleresources. Retrieved from http://cdrpsb.org/download.php?file=researchreport19.pdf

Canagarajah, S. (2015). Clarifying the relationship between translingual practice and L2 writing: Addressing learner identities. Applied Linguistics Review, 6, 415-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0020

Colón, I., & Heineke, A. J. (2015). Bilingual education in English-only: A qualitative case study of language policy in practice at Lincoln Elementary School. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 27, 271-295.

Developing Ell Programs: Lau V. Nichols https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/ell/lau.html Retrieved on September 12, 2019.

Every Student Succeeds Act (essa) https://www.ed.gov/essa?src=rn Retrieved on September 12, 2019.

Garcia, O. (2017). Problematizing linguistic integration of migrants: The role of translanguaging and language teachers. In J. Beacco, H. Krumm, D. Little, & P. Talgott (Eds.), The Linguistic Integration of Adult Migrants/L’intégration linguistique des migrants adultes Some lessons from research/Les enseignements de la recherche (pp. 11-26). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Mouton.

Heineke, A. J. (2014). Negotiating language policy and practice: Teachers of English learners in an Arizona study group. Educational Policy, 29, 843-878. doi:10.1177/0895904813518101

Heineke, A. J., & Cameron, Q. (2013). Teacher preparation and language policy appropriation: A qualitative investigation of Teach for America teachers in Arizona. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 21, 1-25. policy for bilingual education. Applied Linguistics, 31, 72-93.

Johnson, D. C. (2013). Language policy. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Johnson, D. C., & Johnson, E. J. (2014). Power and agency in language policy appropriation. Language Policy, 14, 221-243.

Johnson, D. C. (2009). The relationship between applied linguistic research and language. Applied Linguistics, 31(1) 72-93.

Jong, E. (2008). Contextualizing policy appropriation: Teachers’ perspectives, local responses and English-only ballot initiatives. Urban Review, 40, 350-370.

Kim, Y. K., Hutchison, L. A., & Winsler, A. (2015). Bilingual education in the United States: An historical overview and examination of two-way immersion. Educational Review, 67, 236-252. doi:10.1080/00131911.2013.865593

Mackinney, E., & Rios-Aguilar, C. (2012). Negotiating between restrictive language policies and complex teaching conditions: A case study of Arizona’s teachers of English learners. Bilingual Research Journal, 35, 350-367.

Menken, K. & Solorza, C. (2015). Principals as linchpins in bilingual education: The need for prepared school leaders. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 18, 676-697. doi:10.1080/13670050.2014.937390

Michener, C., Sengupta-Irving, T., Patrick Proctor, C., & Silverman, R. (2015). Culturally sustaining pedagogy within monolingual language policy: Variability in instruction. Language Policy, 14, 199-220. doi:10.1007/s10993-013-9314-7

Moje, E. B., Ciechanowski, K. M., Kramer, K., Ellis, L., Carrillo, R., & Collazo, T. (2004).Working toward third space in content area literacy: An examination of everyday funds of knowledge and discourse. Reading Research Quarterly, 39, 38-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.1.4

No Child Left Behind https://www2.ed.gov/nclb/landing.jhtml Retrieved on September 12, 2019.

Title IV of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oii/nonpublic/eseareauth.pdf. Retrieved on September 12, 2019.

Translanguaging https://www.languagemagazine.com/2018/09/10/a-pedagogy-of-translanguaging/. Retrieved on September 12, 2019.

Thomas, W. P., Collier, V., & National Clearinghouse for, B. E. (1997). School effectiveness for language minority students. NCBE resource collection series.

Viesca, K. M. (2013). Linguicism and racism in Massachusetts education policy. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 21, 1-35.

Laura Arredondo is the Supervisor SIG Representative and the Supervisor of World Languages and ELL Programs at Hunterdon Central Regional High School.

Teacher Education Special Interest Group

“Noticing” As a Tool for Reflection

By Lisa Rose Johnson

As the Teacher Education SIG representative, I feel it is essential to share some general tips and tools that can help to train preservice teachers regardless of their discipline. This article will focus on emerging research in the area of “noticing.” As a skill, “noticing” is essential for all teachers. Teachers who had training in “noticing” will be better prepared to give informal assessments or to use checklists. Also having the ability to “notice” will allow teachers to become effective reflective practitioners who can successfully pass the edTPA assessment.

In New Jersey, 38 Teacher Education programs are requiring students to complete edTPA portfolios as a step towards licensure. As many of you know, submitting the edTPA portfolio is a rigorous process that requires students to videotape themselves and then reflect on their teaching in multiple areas. For those who read this and did not have to endure this process, it’s similar to National Board Certification but for teacher candidates. Many teacher education programs are looking for ways to provide strategies to help teacher candidates to become reflective practitioners by teaching students the art of “noticing.” Research on “noticing is endless, just doing a Google Scholar and searching using the key terms “teacher education noticing” the investigation revealed 168,000 results.

Research related to teaching “noticing” is prevalent in Science Teacher Education, and little research is presently related directly to TESOL instruction. One study from Benedict-Chambers (2016) found that noticing tools were successful in guiding novice teachers to collectively identify, interpret, and share insights to respond to critical issues of science teaching and learning related to using the science teaching practices to support student learning. A second study by Gibson and Ross (2016) revealed that literacy teachers could become thoughtful decision-makers who adapt instruction to students’ needs. Gibson and Ross’s work is also applicable to the field of TESOL as many ESL teachers use the same strategies when teaching literacy.

In addition to scholarly research on the topic, many universities are investing in computer programs that mimic edTPA. One way to do this is through teaching modules. One example of a teaching noticing module that focuses on dual language instruction can be found by clicking here. This multipart series module from the RPMs Partners: FPG Child Development Institute allows for teacher candidates to complete modules. In Module One: Interaction, one of the objectives is to “Observe, interpret and respond contingently to support children’s learning and development in language, cognitive and emotional competence.”The modules can be used for independent practice or as classroom assignment. If you have time these are well worth taking the time to watch them. As the teacher education SIG representative, I’d love to know how you are helping teachers candidates to increase their “noticing” skills? What tools are you using in your teacher preparation programs?

References

Benedict-Chambers (2016). Using tools to promote novice teacher noticing of science teaching practices in post-rehearsal discussions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 28 -44.

EdTPA (n.d.) Retrieved on August 23, 2019 from https://www.edtpa.com/.

Gibson, S.A. & Ross, P. (2016). Teachers’ Professional Noticing. Theory Into Practice Volume 55, (3), Adaptive Teaching: Theoretical Implications for Practice, 180-188. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00405841.2016.1173996.

Module 1 (n.d.) Retrieved on August 23, 2019, from https://rpm.fpg.unc.edu/module-1- interaction. RPMs Partners: FPG Child Development Institute. Puckett Institute | University of Connecticut.

Module 6, Lesson 3. (n.d.). Retrieved August 22, 2019, from https://modules.fpg.unc.edu/rpm/M6L3/index.html

RPMs Partners: FPG Child Development Institute. Puckett Institute | University of Connecticut.

Dr. Lisa Rose Johnson, Ed.D. is the Teacher Education SIG Representative and Editor of Voices.

Features: Fall 2019

Features: Fall 2019