NJ Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages/

NJ Bilingual Educators

Welcome to NJTESOL/NJBE’s Annual Voices Journal. This publication is a representation of members’ thoughts on issues important to ESL, Bilingual, and Dual Language educators in New Jersey and the larger language teaching community. This annual journal has a scholarly approach which reveals the deep commitment our writers and readers have for their teaching practice and students. NJTESOL/NJBE hopes you enjoy our second issue of NJTESOL/NJBE’s Annual Voices Journal and its continuing companion, NJTESOL/NJBE’s Weekly Voices. Annual Voices Journal is the official publication of NJTESOL/NJBE, issued annually each winter. Articles in the NJTESOL/NJBE Voices Journal include current issues, classroom explorations, program description/exemplary scheduling, and alternative perspectives as related to the teaching of English to speakers of other languages, Bilingual Education, and Dual language programs including students who are U.S.-born bilinguals, “generation 1.5”, immigrants, and international students. Articles may focus on any educational level, from kindergarten to university, as well as on adult school and workplace literacy settings.

ARTICLES:

Read with Me

Tina Kern

The benefits and challenges of reading aloud in the ESL/Bilingual classroom and strategies for a successful read aloud program.

Translanguaging Fosters a Framework of Sustainable Cultural Practices in Communities of Color

Pedro Trivella

Considerations on the pivotal role translanguaging has on inclusivity and equity in language while creating cross-cultural connections among English Language learners.

A Place for Everyone – Inclusion for Multilingual Learners

Dr. Denise Furlong

Inclusion for Multilingual learners in mainstream classrooms is essential for students to learn grade level content and achieve academic success; suggested guidelines and implementation practices.

Alternatives to Editing Exercises

Marilyn Pongracz

Implications of using traditional editing exercises in English as a Second Language college classrooms and recommendations for more productive practice supporting English language acquisition.

ELs Require Tier 2 Vocabulary Instruction to Unlock Content Area Learning

Mary K. Mansfield

Focusing on the key to content learning, tier 2 vocabulary is the responsibility of all educators, not just ESL/Bilingual teachers. Practices to share with mainstream and content teachers to achieve the shared educational construct of the WIDA English Language Development Standards Framework, 2020 Edition.

Reflections Learned Through Trauma to Better Support Emergent Learners

Scot Burkholder

An educator’s personal experience with hearing loss creates a space for reflection on educational practices with students and their families.

Read with Me

By Tina Kern

Introduction: A Personal Note

Every night I would read to my children. Our favorite book was Love You Forever by Robert Munsch. Sometimes they chimed in “reading” with me: “I’ll love you forever/ I’ll like you for always /As long as I’m living/ my baby you’ll be.” As time progressed, we would read the refrain in Spanish: “Para siempre te amará, /Para siempre te querré, /Mientras en mi haya vida, /Siempre serás mi bebé.” Eventually they parroted this with me, too young to connect the words to any meaning, but knowing it gave me joy to hear the words as we spoke them together. We communicated and bonded, taking turns, asking questions, embracing the love.

Every night I would read to my children. Our favorite book was Love You Forever by Robert Munsch. Sometimes they chimed in “reading” with me: “I’ll love you forever/ I’ll like you for always /As long as I’m living/ my baby you’ll be.” As time progressed, we would read the refrain in Spanish: “Para siempre te amará, /Para siempre te querré, /Mientras en mi haya vida, /Siempre serás mi bebé.” Eventually they parroted this with me, too young to connect the words to any meaning, but knowing it gave me joy to hear the words as we spoke them together. We communicated and bonded, taking turns, asking questions, embracing the love.

The Importance of Reading Aloud

A statement from the 1985 report from the Commission on Reading, stated: “The single most important activity for building the knowledge required for eventual success in reading is reading aloud to children.” (Anderson, 1985). Jim Trelease wrote several editions of his book called The Read Aloud Handbook. “We read aloud to children for the same reasons we talk with them: to reassure, entertain, bond, inform, arouse curiosity, and inspire. But reading aloud goes further than conversation when: It conditions the child to associate reading with pleasure; creates background knowledge.” (Trelease, 2006). As a result, some homes filled with books as people embraced the importance of reading. Some schools conveyed information and distributed books to families so communities of readers were created. Educators shared the message that reading in any language is critical and leads to success in schools.

Reading Aloud in School

There are definite benefits to reading aloud to students in school. As teachers, we help develop their listening skills. In addition, the skills of patience and paying attention with sustained concentration are developed, skills which are essential when students read independently. As the teacher reads the words become alive so that students are aware that words are not just printed letters on a page. Students can use the skill of visualization as they become involved in the story. As they are introduced to various topics, it is a method of building background, especially with picture books. For ELLs, reading aloud and choral reading can be utilized, especially with chants, patterned text, predictable text, etc. Here the teacher can use gestures and voice to enhance meaning.

Reading in school, though, also holds the key to many other skills that promote success for students. Teachers need to awaken the joy and wonder of reading, but there is a higher purpose, especially as the students get older and need more rigor that only true comprehension of reading and the skills associated with them can achieve. Teachers are passed the baton to foster reading. Their responsibility though, is more multifaceted. There are objectives and curriculum. There is a responsibility to integrate the skills, and create “good readers”. Anchor charts are posted: Good readers make meaning of words. Good readers create pictures. Teachers attempt to ignite curiosity while instructing students in the skills and strategies that will guide them for future success in school. As educators know, reading is the backbone of almost every content area.

With this weighty responsibility, what should teachers be doing to make a difference and promote the highest quality reading lesson? Many times, students are mesmerized by a picture book that elicits visions and fosters imagination. In various forms teachers read to their students in almost every grade. The vast responsibility of carrying on the beauty of reading is innate as teachers. A love of reading is important, but being able to understand the building blocks of reading translates into success in academics in school. Reading takes on a different meaning in the school setting. What is the purpose of being able to read in school? When we go beyond the mechanics of reading, what is the academic purpose that underlies our reading lessons?

When visiting classrooms, one can observe teachers incorporating rigor while filling in the gaps, an almost overwhelming task. As a result, every minute of every school day has gained infinite importance – that there is no time to “waste”. Periods of time are orchestrated like a well-practiced symphony, gathering the types of activities and presenting them for students to be as effective and make the greatest impact.

Sometimes teachers in upper elementary and middle schools read chapters to their students, gesticulating and reading in voices that reflect the mood of the passages. When the bell rings for the end of the period, their reading voice settles, as they reluctantly stop, and dismiss the class. In one class being observed, as students filed out of a classroom, some were suppressing a yawn, some leaving quickly as they disposed of the book that was open to the same page on the desk during the reading. Others left having enjoyed the story, but when it stopped abruptly, did not have a chance to internalize what really happened during the reading. The teacher seemed to be working harder than her students. In fact, some students were not engaged. Two students were playing with their pens. Three students were staring, but not following along in the book at all. Some students were looking down, but not tracking in their books either. The question is, what was the purpose of reading the complete chapter of the book? What did the students learn? What did they understand? The teacher was very skillful in her rendition. She asked several questions, but all were answered by a handful of the same students. Her effort was palpable. If her purpose was to finish the chapter of a book that was part of the curriculum, she was successful. That chapter was over. But the learning was not.

Read with Me and the other articles continue below.

Importance of Reading Complexity

One of the wonderings after that class was to what extent did all of the students understand the text? The class was diverse, encompassing mainstream students and ELLs. The book was complex and integrated some idioms, complex sentences and references to the American past with words that reflected this era. When examining the student population in the classroom and the data, it was found that there were students with a variety of Lexile levels, some quite below the Lexile of the book read to them. In this case, the book was about a 785 Lexile, while some students were only at a 350 Lexile! Lexile is one method to measure the difficulty of a text. This was a group lesson, with expectations that probably couldn’t be met by all of the students. Content, complexity of the text and the reading level must be examined before presenting a text. Maybe this teacher’s purpose was to expose the book to all of the students, one chapter at a time. But what was the “takeaway” from the lesson from the students’ points of view? What did they learn? Was the time used wisely? Could the teacher have used some strategies to engage the students as she read? Beyond that, the question also becomes should teachers be reading complete chapters or books to students? Would smaller excerpts be more productive? What was the next step? If this novel was several hundred lexiles above some of the students’ independent reading level, how would the book be continued, and ultimately completed by them? Perhaps there was another version of the text, one with reduced English text.

One Solution

One solution to offering only one article or text to a class comprised of so many levels is to find readings that have alternative versions of the same material. Teachers must assess the complexity of the text, and then assess the appropriateness of the version for the students. This is an example of “One size doesn’t fit all.” For example, with nonfiction articles, the website, Newsela, presents the articles on various Lexile levels so that the entire class can extract the same basic information, but with comprehensible input, since that site reduces the complexity of the sentences and vocabulary to meet the needs of the levels of the students. There are books and sites that offer various articles and books, or versions of the same basic story on different lexiles and/or grade levels. In this way students can read parallel texts. There are publishers that have classics presented in graphic stories or less complex versions. Also, there are free websites such as CommonLit and ReadWorks, which present the same text on different Lexile levels. The challenge of finding the Lexile of the novel or passage can easily be solved by various online sites. Here is one site: Lookup a Book’s Measure. Sometimes an educator finds a passage that seems apropos to a lesson, but there is no indication of the level. Having an innocuous label “Second Grade” is often deceiving. There are so many factors that go into the determination of a Lexile that sometimes two different sites might deviate by several Lexiles. Teachers can check the levels of some passages by using this tool, the text analyzer. At other times there is a need to reduce the complexity of the text, which can be accomplished at Rewordify.

Passive vs. Active Listening

Another observation is the inattention of some students who could not maintain their concentration for an extended time of listening and concentration necessary for long periods of reading aloud. Kate Kinsella (2021) expounds upon this “passive listening”. To be disengaged from the oral reading, perhaps not even listening at all, means that the lesson is totally ineffective for that student. It is one way communication and mechanical. Many students do not engage in the oral reading activity for many reasons. The story could be too difficult to understand, the language could be too complex, or perhaps the students’ mode of learning is not auditory. There are many methods to create more interaction for students during read aloud stories, especially at the upper levels. There must be active listeners who interact with the lesson.

If teachers are tasked with providing novels as part of the curriculum, hopefully there are parallel texts, or choices of novels so that students can interact with the book and move forward in skills and comprehension. To present a book that is levels beyond the independent reading level of the student defeats any purpose. If the student is being read to by the teacher, then it is understandable if the student is not being engaged, and, therefore, distracted. First, the student will not enjoy the reading, and will be passively listening – or not listening at all. Also, energy will be expelled just to understand the reading, instead of having the reading elevate the skills and move the student forward. Reading then becomes a burden and something to be avoided.

Texts should be broken into manageable segments. In following the teaching method of “I do, we do, you do”, the book can be introduced and a section can be read aloud to activate interest, modeled so that the mood and style is established, and lead to the next part, “we do”. Here the teacher can involve the students by incorporating strategies such as cloze or echo reading. When the students have a copy of the book or a chapter, the students can be active participants. If a copy is not available, the section can be projected, or part of the chapter can be scanned, provided online to the student or they can have a hard copy. In cloze reading, the teacher can alert the students that certain words, phrases or sentences will be read by the students. As the teacher models this technique, she reads and then pauses. With gestures, the students are encouraged to continue when the teacher pauses until the end of the sentence. Echo reading is when a teacher reads sentences or parts of a text to model the reading for the students. The students repeat the section after the teacher in order to build oral fluency and accuracy. It also helps promote interaction.

Kate Kinsella (2021), in a recent webinar hosted by Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, talked about other factors that are not conducive to fluency and reading comprehension, including popcorn reading. In popcorn reading, a student reads and then chooses another student to continue reading after they say, “Popcorn”. During this activity, many students try to ascertain what they will be expected to read, and concentrate more on the ability to read the words aloud, instead of putting all of the parts together for comprehension. There are other more purposeful effective strategies to hold the attention of students and check for understanding.

When reading aloud, the students must take ownership of the reading, feel included and delve into the reading with purpose. To that end, the teacher should be providing background knowledge so the students get ready for the journey they will take together. The teacher should introduce vocabulary that is integral to the meaning of the story. Providing the words and the meanings will allow the students to concentrate on the other reading skills and help the student comprehend the selection. Checks on comprehension can be accomplished by infusing questions, discussions, double entry journals and graphic organizers, among other activities. Student led discussions and creative projects, such as Flipgrid videos can be planned to check comprehension.

Conclusion

Teachers must distinguish between recreational reading, informational reading, and instructional reading. When reading is the means to navigate the academic world of school, then the lesson must be planned so that reading is a vehicle to that end. The joy of reading is then couched within the strategically planned lesson so that students are seamlessly led through the skills and strategies to boost their understanding and infuse knowledge that will be added to the students’ toolboxes as they continue their education successfully.

The Author – Tina Kern is a Professor-in-Residence at William Paterson University, and provides professional development, coaching and mentoring at two schools in the Paterson School District. She is also an adjunct professor at WPU and Kean University, with an MA in education, and NJ certifications in ESL, Bilingual Education, English, Spanish, and Elementary Education. Her experience includes mentoring teachers, being a Program Assistant and teaching ESL, and Bilingual Language Arts in the Morris School District for 30 years.

References:

Anderson, R C. (1985). Becoming a Nation of Readers: The Report on the Commission Reading. Washington Institute of Education, Washington, D.C.

Kinsela, K. (2021). Techniques and Tools for Supporting Multilingual Learners in Interpreting and Constructing Informational Text. [Webinar]

Trelease, J. (2006). Why Read Aloud to Children. [Brochure].

Translanguaging Fosters a Framework of Sustainable Cultural Practices in Communities of Color

By Pedro Trivella

As an ESL/Bilingual educator and a second language learner myself, I know firsthand the pivotal role that inclusivity and equity play in language and cross-cultural connections among English Language learners.

Culturally Sustainable Pedagogy fosters racial and ethnic equity and promotes equal opportunity across all diverse communities. CSP strengthens ELs’ identities needed to critique and question dominant power structures in societies. Gloria Ladson-Billings (2019) supports translanguaging pedagogy as an integral component of the framework of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy (CSP).

Translanguaging, the language practices of bilingual/multilingual individuals, enables ELs to successfully navigate through their acculturation process by encouraging them to embrace their dual language and cultural efficacy as viable and valuable resources to maximize their pedagogical and life goals. According to Garcia (2014; 2018), translanguaging positively impacts both LEP learners and native English speakers since it opens up opportunities and exposure to other languages and cultures, while simultaneously validating the importance of bilingual/multilingual practices.

Translanguaging is currently recognized for its integral role in education. Baker & Wright (2017) theorize that bilinguals naturally use their known languages to amplify their learning. I agree with Garcia (2014) that the practice of translanguaging emphasizes the participants’ flexible use of their complex linguistic resources to make meaning of their lives and complex acculturation process.

While considering translanguaging as a pedagogical practice, I have realized that students’ dual linguistic assets are not limited to how they communicate, but also reflect their identities and way of being. Consequently, I am able to capitalize on the students’ knowledge base and capabilities as a resource, and the students’ home language practices can be used to promote meaningful and lifelong learning. I distinctly recall tapping on my first grade ELs Spanish knowledge of the word “habitar”, in order for them to understand the content vocabulary word “habitat” while reflecting on both words’ cognate transferable elements.

Inspired by Cummins (2017) theory that languages do transfer throughout the learning process, and literacy transfers across languages and language systems as learning advances, I have broadened my view regarding language and content. Rather than seeing language and content as two separate, independent systems, I embrace a more flexible and holistic methodology that views multilingualism as playing a strategic role in content mastery.

According to MacSwan, J. (2017), the following are educational benefits of translanguaging:

- The ability to build on students’ metalinguistic awareness by comparing and contrasting language forms and systems.

- Students’ recognition that they can use different languages strategically to enable comprehension and production, creating a bridge between the languages and content concepts

- Student awareness and validation of the role language practices play in their lives at home, in school, and in the larger community

- The ability to address multilingual audiences and negotiate meaning across languages

- Multiple language resources to engage with complex and abstract content area information and material; to acquire content information and academic skills from different sources; and to self-regulate

- Experimentation and interaction with language resources to develop/use divergent thinking and creativity.

Embedding translanguaging methodology in my learning space is done purposely and strategically by clearly distinguishing between a “bridge” and a “bridging” approach. Beeman & Urow (2013) distinguish between “bridging” and “The Bridge.” In “bridging,” the two languages are brought together to encourage students to explore and reflect on the similarities that lend themselves to knowledge and skills transfer between both languages. The Bridge, on the other hand, is the systematic development of units of study in dual language programs in which one language is used to teach concepts and skills; at the close of the unit, those concepts and skills are deliberately bridged to the other instructional language through an activity such as a bilingual anchor chart or comparison of language forms. Finally, an application unit in that other language follows. Whether used as an active teaching methodology, or as a student support system, instructional translanguaging is always used deliberately and strategically.

Embedding translanguaging methodology in my learning space is done purposely and strategically by clearly distinguishing between a “bridge” and a “bridging” approach. Beeman & Urow (2013) distinguish between “bridging” and “The Bridge.” In “bridging,” the two languages are brought together to encourage students to explore and reflect on the similarities that lend themselves to knowledge and skills transfer between both languages. The Bridge, on the other hand, is the systematic development of units of study in dual language programs in which one language is used to teach concepts and skills; at the close of the unit, those concepts and skills are deliberately bridged to the other instructional language through an activity such as a bilingual anchor chart or comparison of language forms. Finally, an application unit in that other language follows. Whether used as an active teaching methodology, or as a student support system, instructional translanguaging is always used deliberately and strategically.

Either deliberately utilizing translanguaging as an active teaching methodology (bridging) or as a student support system, both serve as beneficial tools. My teaching experience shows that “bridging” is highly effective when working with ELs. Additionally, engaging my ELs that possess higher English Language proficiency skills has also proven to be successful.

Some of the translanguaging initiatives that I have implemented in my second language learning environment are:

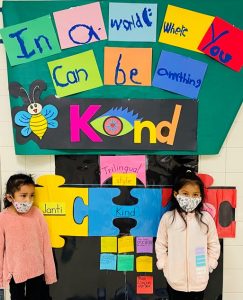

1. Be Kind – Trilingual Style:

1. Be Kind – Trilingual Style:

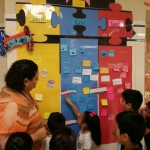

The “Be Kind – Trilingual Style” BASTA initiative fosters a safe and respectful learning space to engage all learners, regardless of their English language proficiency levels. Students were encouraged to write in various languages (English, French Creole, and Spanish) personality traits that exhibit their gentle, respectful and kind manners. The “Be Kind – Trilingual Style” strategy enables students to increase their confidence and writing efficacy while engaging in reflective and self-regulatory agency.

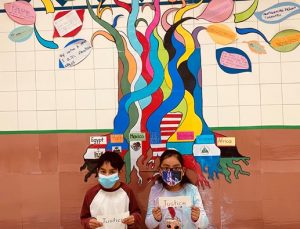

2. Our School Global Tree:

2. Our School Global Tree:

Learners reflected on their powerful multilingual and multicultural agency by adding leaves to our school Global tree. Students wrote about significant cultural contributions that they and their families bring to our school community and neighborhood. Additionally, children evaluated and internalized our dual “2 is better than 1” academic vision.

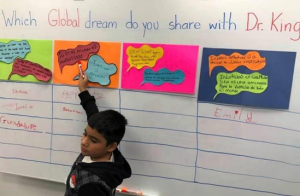

3. “How Else to Say It” Dr. Martin Luther King Legacy:

3. “How Else to Say It” Dr. Martin Luther King Legacy:

Students demonstrated understanding of MLK legacy by engaging in a Fulbright “How else to say it and why” activity in which they wrote in their own words (In English and/or their home languages) to individually or collectively their interpretation of their favorite Dr. King’s quote.

4. Professor Trilingual – Our School Mascot:

4. Professor Trilingual – Our School Mascot:

Professor Trilingual was created as a result of 2nd grade students who voiced their concerns regarding the fact that the Scholastic I-Read program characters are only monolingual.

Students evaluated and built consensus regarding Professor Trilingual’s design, that he should have three mouths to reflect the three languages that they spoke (English, Creole, and Spanish), one nose because we should all be able to breath the same air , and one eye since we all have the same vision of achieving our American Dream.

5. Cat in the Hat Challenge:

5. Cat in the Hat Challenge:

Learners were challenged with a problem: Cat in the Hat left his hat in the automat! Second graders designed and created a new hat for Cat in the Hat that symbolized their multicultural backgrounds as well as our Asbury Park beach community. Thereafter, students collectively wrote a translanguaged book to express their gratitude regarding this special visit.

6. “Nuestros Sonidos Latinos” – Monmouth University Radio Station Show:

6. “Nuestros Sonidos Latinos” – Monmouth University Radio Station Show:

The students conducted a two hour radio show at Monmouth University’s radio station. “Estudiantes” discussed the benefits of being bilingual and reflected on the challenges and rewards they have experienced while learning English and acculturating to their new American home. Our superstar students even turned the table on the Monmouth University students and staff and asked them about their motivations to learn Spanish.

Translanguaging lends itself to reflective opportunities for my students to embrace active roles in lessening inequalities and injustice by spearheading civic/community problem-solving initiatives that improve their learning communities and neighborhoods. Routinely embedding translanguaging practices among my ELs has significantly strengthened the powerful diverse language agency they possess. Translanguaging offers students authentic reflective practices that enable them to evaluate, negotiate, and identify how and when to blend their dual language superpowers.

The Author, Pedro Trivella, is a driven global ambassador with a multicultural DNA. The unique language acquisition and acculturation challenges that he experienced have enabled him to empower ELs and their families with the academic agency and life skills that meet their particular needs. Becoming a Fulbright scholar and creating the BASTA Multicultural committee have served as a pivotal vehicle to foster his Multilingual Global advocacy.

View the images in a gallery.

REFERENCES

Beeman, K., Urow, C. (2013). Teaching for biliteracy: Strengthening bridges between languages. Caslon Publishing.

Cummins, J. (2017). Teaching for transfer in multilingual school contexts. In García, O et al. (Eds.), Bilingual and Multilingual Education, Encyclopedia of Language and Education, Springer International Publishing AG, 103-116.

Garcia, O. (2014). Translanguaging as normal bilingual discourse. In Hesson, S., Seltzer, K., Woodley, H.H. Translanguaging in curriculum and instruction: CUNY – NYSIEB guide for educators. CUNY Graduate Center.

MacSwan, J. (2017). A Multilingual perspective on translanguaging. American Educational Research Journal 54. 167–201. doi:10.3102/0002831216683935

A Place for Everyone – Inclusion for Multilingual Learners

By Dr. Denise Furlong

The general education classroom is sometimes viewed as an exclusionary place that one needs a “golden ticket” to enter. Students with learning disabilities, linguistic diversity, varied learning styles, or behavior challenges may not have access to that ticket–or their ticket may indicate that they are “standing room only” (or a probationary basis). There may even be an invisible line that separates children by their race or ethnicity. When placements in different types of classrooms are viewed as a reward for privilege, the system is broken.

The general education classroom is sometimes viewed as an exclusionary place that one needs a “golden ticket” to enter. Students with learning disabilities, linguistic diversity, varied learning styles, or behavior challenges may not have access to that ticket–or their ticket may indicate that they are “standing room only” (or a probationary basis). There may even be an invisible line that separates children by their race or ethnicity. When placements in different types of classrooms are viewed as a reward for privilege, the system is broken.

All students–including Multilingual Learners (MLs)–are entitled by law to education in the environment with the fewest supports that they need in order to be successful. This means that these students are not isolated from their peers in self-contained programs if it is not absolutely the most appropriate environment for them. For many students, this appropriate placement may be in a general-education classroom with their peers along with language supports or other differentiation within that classroom. The types of supports that students may need are as individual as they are and should not be determined by what the school “typically” provides for students. In fact, when we discuss the needs of “diverse learners,” we must understand that all students have diverse needs, not only the ones who look “different.”

When considering placement decisions for MLs, the lack of preparation of the teachers to teach diverse learners cannot be part of the equation. It is the responsibility of the school district to ensure that all educators are trained and supported in meeting the needs of all learners. Inclusion within the general-education classroom is not always executed in the manner that meets the needs of diverse students, but when it is done correctly, it is beneficial to all students. Following is a list of non-negotiables that support a successful environment for inclusion.

Ten Commandments of Inclusion

- All learners have the right to the education that is most appropriate to their needs.

- All learners have the right to highly-qualified content-area teachers or specialists who are trained in inclusion and co-teaching.

- Access to grade-level curricula for everyone is crucial for every learner.

- All learners belong. All teachers belong.

- The objectives are the same for all learners; the manner in which different learners achieve the objectives may vary.

- All teachers are responsible for all learners in the class.

- Co-teachers must have time together within their contractual day in which they can plan.

- No learners are marginalized (geographically, academically, or socially) in the class.

- Diversity is valued and celebrated in class (and in the school community).

- Administration must be knowledgeable and strong proponents of co-teaching models.

Questions may arise when considering these commandments of inclusion. Why are these commandments critical to the success of all learners? How do educators ensure that these commandments are respected in all classes with all learners? What message does our commitment to inclusion and diversity give to our school community as a whole? What do these commandments look like in action?

Although number 10, strong advocacy by school administration is the essential building block to empower a culture of inclusion for MLs and provides the space for many of the other commandments. This is evident in the creation of teachers’ and students’ schedules, the hiring process, classroom observations and professional learning opportunities for all staff, and the constant reflection on what they can do better to fully meet the diverse needs of all students. Cecilia, an ESL/Bilingual supervisor, reports that she maintains open communication with her teachers of MLs and is amenable to making schedule changes or adapting individualized support for MLs to best meet their diverse needs (C.Zimmer, personal communication, February, 2022). This flexibility and communication are critical, as it is imperative that all educators understand that scaffolds and supports for diverse students may change as their language proficiencies increase or their academic needs become more apparent. This is also an important factor as “Newcomer” students arrive into districts. Administration must ensure that the environment of the school welcomes and celebrates all cultures that are represented by the community; it must be evident in the classrooms, all curricula, and within the school environment as a whole. School culture like this is more than the token multicultural assignments at different points in the year; this is a living and breathing component of a representative and connective pedagogy that is essential for all students.

Dr. Ilene Winokur discusses the critical need for belonging in schools, especially for MLs (2021). This sense of belonging can be fostered by several of the ideas within these commandments. MLs have the right to access to grade-level curricula in a setting in which they learn collaboratively with their peers. This does not mean that they are “guests” in a general education classroom, or that they all sit together in the back corner of the room. They (and their teachers!) are integral parts of the classroom community and deserve to interact with their peers in all activities. Allyssa, a 7th grade general education teacher, reports that constant conversations with her in-class support teachers are required to adjust activities in her class to ensure access for all learners (A.Townsend, personal communication, January, 2021). She recalls a time in which her class participated in a “Readers’ Theater” activity in which her students acted out parts in a play about the American Revolution. All students were assigned parts – even her MLs. With the support of the ESL teacher, scaffolding, and lots of practice prior to the activity, all students participated in this activity that was memorable for everyone. One of Allyssa’s general education students commented on how she loved working alongside her peers who so bravely spoke out in a language that they were still learning. Creating this kind of atmosphere of support and the celebration of “risk taking” is essential for all students to feel a sense of belonging and opportunity for growth.

Consistent and evolving professional learning for all staff members is a crucial part of establishing and maintaining an environment that supports successful inclusion. According to Furlong and Spina (2022), educators at all levels must be empowered to make change, acknowledged for their expertise, and supported in their needs through professional learning and connections. Administrators cannot assume that teachers and paraprofessionals seamlessly understand how to work together to meet students’ diverse needs, in addition, administrators must listen to staff to understand the specific dynamics of each class and provide support in whatever ways that benefit the students. Opportunities for individualized, targeted, and supportive professional learning for all educators are critical to creating a school environment in which everyone is a learner in order to provide educational excellence.

Why inclusion and why co-teaching?

In the past, students who had needs other than those of the mainstream were placed in different settings to accommodate those needs. Only the students who met certain criteria were “invited” to the general education classrooms. This type of segregation is harmful to all students–not just those being excluded. Not every student’s best placement is an inclusion setting, but all students thrive in environments where all types of diversity are embraced.

Inclusion has historically referred to a class in which there are students who have IEPs (Individualized Education Plans) learning alongside general education students. More recently, however, this format has also included MLs who are in general education classes learning through a co-teaching model with a certified ESL teacher. When MLs have access to content-area experts alongside their native-English-speaking peers, they have the opportunity to learn content and language in a way that is authentic and accessible. To be clear, MLs are entitled to this type of equitable learning; it is only now that districts are recognizing that they must meet MLs needs in this way. “It is critically important that all educators see themselves as language teachers, no matter what is on their certificate” (Spina, 2021, pp. 33-34).

As all learners have access to the general education classrooms and curricula, they also gain much more. The sense of belonging in the school community is crucial for students’ SEMH (Social Emotional Mental Health) and their academic progress. Winokur (2021) explains how students need to feel “safe, valued, and included” (p. 91). As learners feel that sense of belonging, they often will participate more in the school community outside the classroom, providing them with other types of connections as well as different forums in which they can develop language. As activities within the school and community reflect the diversity of the population, more learners gain access to those feelings of belonging.

It is important to acknowledge the qualities of an effective and accessible co-teaching model. All educators are empowered and respected as teachers who are “responsible” for all students in the room; it is crucial to establish this mindset immediately to avoid separation into “my students” and “your students.” A truly cohesive class setting benefits all students through the respective expertise of two (or more) educational professionals. A co-teaching model with a content-area expert and an ESL teacher sends a message to the students that diversity is something to embrace and celebrate. No one teacher is more “important” in the class, and no one group of learners is the target audience. When teachers model that all students have different needs and perspectives–and they all are valuable and an integral part of the class–they build that sense of respect and connection within the community. The entire school community, administrators, teachers and students become stakeholders in everyone’s success.

Representative & Connective Pedagogy

Inspired by Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 2021), Representative and Connective Pedagogy is a movement that defines the goals of inclusion for MLs. It is important that schools and teachers create an environment in which all students (and staff!) feel as if they belong there. This can be achieved through reflection on teaching practices, materials that include diverse perspectives and experiences, and a community in which differences are celebrated. Also crucial is professional learning available to all educators about diversity, SEMH, and ways to make all content accessible to all learners.

Representative and Connective Pedagogy:

- empowers all learners and fosters connections among them;

- acknowledges, values and celebrates the diversity of learners and educators;

- bridges gaps between languages, cultures, perspectives in ways that benefit all;

- creates a culture of acceptance/celebration in the classroom/school;

- provides an environment in which all learners feel safe and willing to take risks;

- encourages collaboration with and among diverse learners;

- includes literature that represents all learners in all curricula;

- analyzes curricula and ensures that different perspectives are represented;

- builds schema for all learners in diverse topics/cultures;

- prioritizes relationships and connections in classrooms/communities;

- understands that learners’ families are a integral part of their identities;

- meets varied educational needs with dignity and age-relevant materials

It is important to understand that diversity–even among MLs–includes differences in many aspects of life. Diversity includes (but is not limited to): Language/culture/ethnicity, race, family structure, gender roles and identities, abilities, sexual preferences, communities/SES, SEMH perspectives, medical differences, physicalities, academic abilities and challenges, interests, talents, past school experiences, responsibilities outside of school, social issues, and shared experiences. Educators must intentionally reflect upon the various ways that our MLs are diverse within their interactions with them and seek ways to connect with them through those differences.

Representative literature in class read alouds and libraries that provide mirrors, sliding doors, and prisms for them (Krishnaswami, 2019) must include the many different ways the school community is diverse. The languages spoken by learners and teachers in the classroom are included in everyday activities. Collaborative learning groups are intentionally and dynamically designed for purpose-driven activities and provide all learners with opportunities to communicate and connect with peers. Educators are knowledgeable and cognizant of cultural and educational differences that affect students’ behavior and academics and understand best ways to support them. Educator biases are acknowledged and reflected upon and ways to overcome them is at the forefront of all conversations and initiatives. Educators have a safe space to acknowledge their own challenges and receive support without judgment.

Some MLs come to school districts having experienced schooling in a different way that is typical of students in the United States. These students may be SLIFE (Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education), or their educational experiences may have had a different focus than our schools. Kara, a 5th grade general education teacher, describes a student whom she taught in the past whose education in his native country was with a local shaman rather than a “traditional” classroom setting (K.Holler-Perez, personal conversation, January, 2021). While these school backgrounds do not “match” those of students in the United States, these children all have had valuable learning experiences–in and out of school. Educators of all diverse learners must build on these unique experiences and leverage those learning opportunities that build their schema and knowledge of the world.

Another way that embracing and celebrating diversity is evident in schools is the representation of diverse populations in extra-curricular activities or other honors. Are MLs elected to student council or chosen to be captains of sports teams? Are they peer leaders, members of honor societies, or chosen to be in focus groups to represent the voices of their peers? What is the percentage of MLs who have access to gifted and talented or enrichment courses? Schools can provide whatever points of access are necessary in the classroom by means of fulfilling requirements, but the true measure of representation and connection is the diversity of the opportunities outside class that is integral to the school community.

Final reflections

Inclusion for MLs is necessary to provide equity in education for all members in the school community. When diverse learners (read: all students) work together on both content and language objectives, they become stakeholders in one another’s success. These students become empowered and knowledgeable about varied views, abilities, and perspectives. Those community connections forged through collaboration in the classroom provide skills that will benefit them throughout their lives.

The Author – Dr. Denise Furlong is an Assistant Professor/Director of the Reading Specialist Program for Georgian Court University. She has taught MLs for over twenty years in the New Jersey public school system, ranging from kindergarten through 12th grade. She is the author of Voices of Newcomers: Experiences of Multilingual Learners (2022). You can connect with her on Twitter @denise_furlong.

References

Furlong, D., & Spina, C. (2022). Holistic professional learning in times of crisis. In Wilmot, A.,

& Thompson, C. (Eds.), Handbook of research on activating middle executives’ agency

to lead and manage during times of crisis. [Manuscript in preparation]. IGI

Global.

Krishnaswami, U. (2019). Why stop at windows and mirrors?: Children’s book prisms. The Horn

Book, Inc. https://www.hbook.com/story/why-stop-at-windows-and-mirrors-childrens-book-prisms

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Asking a different question. Corwin

Press.

Spina, C. (2021). Moving beyond for multilingual learners. EduMatch Publishing.

Winokur, I. (2021). Journey to belonging: Pathways to well-being. EduMatch Publishing.

Alternatives to Editing Exercises

By Marilyn Pongracz

Over the years, changes have been made in pedagogy in teaching English as a second language, but some untested common practices remain, passed from one textbook author to the next with no proof of their efficacy. One of these is error correction exercises in ESL textbooks.

While there is general agreement that students who are learning English as a second language need to be able to speak and write it accurately for jobs and life obligations, (Tran, 2013) how to help them accomplish this efficiently and successfully is often debated.

To deal with students’ errors, many researchers have concluded that grammar is needed to know what is correct, and when paired with communication, it is beneficial (Foppoli, 2020). However, even students who know the rules do not generally apply these to their speaking and writing.

This occurs because reading, writing, and speaking are complex tasks, and paying close attention to details, such as correct grammar, can hinder these processes (Stockton, 2014). As a result, students make a lot of errors as they learn English. However, if learners make mistakes as they write or speak, those errors are reinforced and more likely to be repeated, eventually becoming automatic and in time, fossilized (Szynalski, 2011).

To address this problem, most grammar and writing books for college-age students conclude grammar lessons with “Find and Correct the Errors” exercises. In my position as the supervisor for tutoring ESL students at Bergen Community College, I can watch and listen as tutors work with their tutees. Sometimes I hear students articulate their thought processes, and I have worked one-on-one with them myself. Students at all levels often struggle with these exercises, which get more complex as students advance.

Whereas in class, a student who does not know an answer can rely on better performing peers, the issues with the find the error exercises become apparent in one-to-one tutoring. This is how a typical session proceeds. A student will show the exercise to the tutor and voice their confusion. The tutor will have the student read the first sentence with an error and ask the student where they think the error might be. The student is clueless, so the tutor might go back to the chapter in the book and discuss the grammar in question. Then the tutor has the student look for that grammatical structure in the exercise as the likely place for the error. The student still may or may not be able to identify the structure, and if not, the tutor will give a hint or finally point it out. If, after reading the sentence a few times, the student can find the correct structure that likely contains the error, they proceed to the remaining questions in the exercise. After two or three sentences, the student may begin to be able to find the errors if these remain consistent. However, if an error is not in the target structure, the student flounders again, rereading the error until the tutor gives the student another hint, and finally, the answer.

From my experience and observations, doing find and correct the error exercises as homework seems to be more detrimental than helpful. Because they are unable to recognize what is correct and what is not, students read the sentences many times trying to find what is wrong, and in the process, repeat and memorize errors. While this exercise may have some benefit for native speakers of the language, it seems to function as negative input for English learners. It is important to note that this type of exercise is not done in any other field: art, music, sports, math, history, or even other language classes. In fact, no research has been conducted to prove the benefit of this type of activity. Yet this exercise appears in almost every college ESL grammar and writing text.

Others’ Observations

I am not alone in my observations. A few bloggers have mentioned the same idea. The key seems to be familiarity with the correct form. Students must know what they are looking for. Grammar concepts are taught, but texts rarely provide enough practice with the topics for mastery. It follows then that if students do not have enough experience with the concepts or know them well, they are not able to identify their errors. Mark Pennington (2019), a teacher and author of grammar, writing, and reading intervention texts, states, “How can you tell if something like a [punctuation] mark is missing if you don’t know where it is supposed to be in the first place?” In fact, he points out that errors “…teach what is wrong, not what is right. …The more visual and auditory imprints of errors, the more they will be repeated in future student writing.”. Taylor (2017), another teacher and web author agrees that having students “…investigate and explore incorrect and poorly written sentences in an attempt to fix them” is not beneficial. Class time would be better spent having, “…rich discussions about what DOES work in a sentence or short passage.”

The ambivalence or possible logic for these exercises is evident in the following email correspondence with Thu Tran, who presented a workshop on writing at TESOL 2021, and has researched error correction for writing. In reference to his paper on feedback in writing, I presented my views and asked for his opinion about error correction exercises.

He began his reply with qualified agreement that students must have advanced skills and understand the text. “Admittedly, that kind of exercise is difficult as it requires a tremendous amount of linguistic knowledge to first comprehend the text, identify the errors, and finally correct them. … If students are not ready to move to edit the target structures, the point you made is absolutely correct.” (T.H.Tran, email, April 1, 2021) Thus, in this he agrees that students must have a thorough knowledge of the grammar before they can do editing exercises.

Nevertheless, many teachers use these exercises in class because they are usually at the end of chapters when students supposedly have learned the structures covered, and these would help them find and correct errors in their own writing. These exercises might also serve to provide an opportunity for further explanations. However, this is in a class setting and does not evaluate how students can or cannot successfully complete these exercises independently or the benefit they provide.

Tran also stated, “In my writing classes, I highlighted problematic sentences in paragraphs and essays students submitted and asked the whole class to identify problematic areas and find ways to improve them. Most of the time my students were able to find and correct their errors. This is a frequent activity in my writing class.” (T.H.Tran, email, April 1, 2021) Demonstrating corrections from students’ writing is helpful as a group activity, but it is not the same as textbook error-find exercises given as independent assignments.

In addition, when doing any error correction exercises in class, stronger students or students with similar grammar in their native languages will be able to identify the errors and carry the class. For example, Spanish speakers can often identify errors with articles, and Asian speakers may find verb tense mistakes. The results of working with a teacher in class is quite different from working individually on homework. It follows, then, that there is not necessarily a correlation between finding and correcting students’ errors as a group in class and having students try to find them in a book exercise while working independently.

Error Repetition

Insights into the causes of recurring errors highlight why error correcting exercises are harmful and why alternatives are necessary. In my own experience of years of playing classical piano, if I make a mistake once and notice it, it can be fixed with one careful repetition of the passage. If I make the same mistake a second time, fossilization has begun. Simply making the same mistake twice is enough reinforcement to repeat it. It follows then that if students are hunting for errors and repeating the errors in a homework exercise, it is likely that they will repeat them.

Khazan (2016), a researcher who analyzed the thinking process, offers his own description of why errors are repeated. The example given is of trying to retrieve a word from memory. If you cannot remember a word, but eventually you finally think of it, you think you will remember it, but you don’t. You don’t remember it because you made a pathway of the forgetting process, and the next time your brain follows the same path of forgetting. Therefore, in the same situation, the error will be repeated and focusing on the error will only reinforce its repetition. It follows then that when students are working on error-correcting exercises, they are reinforcing the errors as they try to figure out where the incorrect grammar is located.

Error Correction

Although these exercises should be abandoned, adult students want to know what errors they are making and the grammar behind the correction. In fact, they need to be corrected. The author of the Joy of Languages blog advises giving students immediate feedback and afterwards, practice using the correct forms. She suggests working on specific aspects of the language and breaking down the problem area into manageable sections (Katie, 2018). In his book, “Mechanically Inclined”, Anderson (2005) is more specific. He recommends focusing on one error at a time. If everything is corrected, then students will not remember the corrections (p. 12). If the goal is incremental and specific, it is easier to reach. Additionally, other experienced educators recommend correcting a single type of error because it reduces, “…the cognitive and linguistic loads” (Witt, et. al, 2020).

Being able to correct errors is helpful, but the goal should not be error correction, it should be producing the correct form so that correction is not needed. Production of the correct form needs to be a habit. Focus on producing a single correct form is a way to build it into a habit, which can be followed by another correct form at a later time. “BJ Fogg, a researcher at Stanford University, is the king of starting small with new habits. His program, Tiny Habits, encourages people to focus on building the habit itself, rather than worrying about how big the impact is” (Cooper et al., 2020). Understanding that it takes time to build habits, even as long as two months, will encourage patience and persistence (Cooper et al., 2020). Creating habits requires a lot of practice. I discussed this with William Jiang, PhD, a professor at Bergen Community College, relating it to his favorite sport, basketball. He stated that every hour of coaching needed to be followed by ten hours of practice (personal conversation, November 24, 2020).

However, practice without concentration minimizes its benefits, and practice requires motivation. Variety in the types of practice can help concentration and motivation. Requiring recall through questions, games or tests is also a degree of motivation. Most importantly, students need to grasp the relevance of the lessons. “In order to make your learning stick, it’s important to make real life connections and see how it fits in the larger scheme of things” (Gani, 2017). For adult learners, understanding the importance of writing and speaking correctly and explaining its purpose can be motivating.

Mentor Texts and Modeling

Avoiding errors rather than fixing them can be accomplished by focusing on the correct forms through modeling using authentic texts. Pennington (2019) acknowledges that error analysis is necessary, but states that the greater amount of time should focus on good mentor texts. Anderson (2005) also espouses the use of mentor texts, “Mentor text shows the error in another light: the light of correctness. If students are going to stare at writing and talk about it, they must see powerful writing models.” (p. 61) In a book review of Grammar for Middle School: A Sentence Composing Approach by Don and Jenny Killgallon, an educator, Ovadia (2013), reports on the success of using mentor texts with her middle school students. The Killgallon books provide extensive analysis and imitation of mentor texts.

In describing a methodology for using mentor texts, Foppoli, a teacher of English and Spanish as second languages, states that students should be provided with authentic language that they read first for comprehension, and then analyze for the targeted grammatical structures, which are taught and then practiced in communicative activities in class. He suggests that homework can be drill exercises which reinforce the concepts taught in class (2020). Alison (2019), a literacy specialist and the author of “Learning at the Primary Pond,” teaches her young students to edit first by showing students examples of good writing which they can imitate, modeling the editing process, and employing carefully guided peer review with specific, clear criteria with visual support.

Sentence frames, which function as partial mentor texts, can be used to scaffold student writing. The authors of “They Say, I Say,” describe these as templates. They point out that experienced writers have a toolbox of “moves” that they use when they write, much like basketball players or jazz musicians. Student writers have not built up this resource, but templates enable students to focus on content and have the tools for good writing. While some may argue that this stifles creativity, the authors contend that, “Ultimately then, creativity and originality lie not in the avoidance of established forms but in the imaginative use of them” (Graff et al., 2012). Sentence frames can help ELs communicate without getting bogged down by grammar rules. They provide structured language that gives them the opportunity to write, think, and talk about concepts using academic language. They can help learners express ideas that are a little above what they could produce without assistance (Carrier, 2005).

This has proven successful in my classes. In a class of beginning adult learners, I had the students change content words but keep the structures of the sentences in models of short paragraphs. To teach basic essay format to intermediate writing classes, I gave them a few basic sentence frames for thesis statements and topic sentences, such as, “The first reason is that…” Using these, they had no trouble writing thesis statements or topic sentences. An ideal resource for frames and collocations is The Corpus-Based Word Combination Card (Alves, 2012).

Other examples are:

“The author’s main message is ____because in the story ____.”

“The author wants us to know that ____.”

“Oranges are _____, however bananas are _____.” (Reyes 2015)

Some teachers express concern that modeling and sentence frames make the work too easy, However, these can help students focus on the task rather than waste time wondering how to start. (Witt et al., 2020) Templates are used to write resumes, create flyers, and put together presentations and more, so why not use these for writing?

Variety

To enhance students’ focus and concentration, modeling and imitation can be presented in a variety of ways. The first is making it personal. In writing classes, when I present my own level appropriate examples of what I ask my students to do, the results are much better than using only textbook examples. A few other teachers have tried this with the same results. Imitation can be fun and can involve all aspects of language production. In a speech class, to help students focus on the details of language and produce it correctly, I had them transcribe commercials and then try to mimic the pronunciation and inflections of the commercials. I had to assist with the transcriptions, but the repeated listening practice had a purpose, and it helped the students focus on vocabulary, syntax, and pronunciation.

Finding and analyzing grammatical structures in authentic texts is another exercise. For example, for students whose languages do not include articles, highlighting a, an, and the on a page of text is a revelation. Then identifying why these are used gives purpose to the exercise. Other successful activities with mentor texts include taking a text and changing the time frame from present to past or from singular to plural, combining short sentences, or replacing words with synonyms. This requires intense focus on the correct, original text. Matching two halves of a list of sentences can also provide the opportunity to examine authentic text. Another option is that after reading a text, select sentences can be broken into four to five chunks which are given out of order for other students to reorganize into sensible sentences. Alternatively, sentences can also be expanded into several repetitive sentences which students have to combine and reduce to their original form.

A third strategy is to have students reteach concepts to each other which helps them remember and apply what has been taught. “Because when we learn with the intention to teach, we break the material down into simple, understandable chunks for ourselves. It also forces us to examine the topic more critically and thoroughly, helping us to understand it better” (Gani, 2017). This is a recommended strategy in tutoring: to have the student explain a concept back to the tutor to check comprehension.

Conclusion

Being the ESL tutoring supervisor at Bergen Community College has given me the opportunity to observe language learning from a one-to-one, individual perspective. From this point of view, and in helping students who want to excel as well as those who struggle with their learning, I have been exploring options to find the best strategies to help students reach their goals. This also involves questioning common, but unsubstantiated practices and finding alternatives.

The Author – Marilyn Pongracz is the ESL tutoring supervisor at Bergen Community College and teaches one of the classes in the ESL program there. Often working with students who are struggling to learn English, she has developed alternate activities and approaches to assist these learners.

In 1999, she created the first version of website pages with activities and links for extra English practice for her students. https://bergen.edu/elrclinks. In 2002, she volunteered to become the Technology Coordinator for NJTESOL/NJBE, growing the online presence of the organization from information pages to its current iteration.

References

Alison. (2019, June 21). 5 Effective Strategies for Teaching K-2 Students to Edit Their Writing. Learning at the Primary Pond. https://learningattheprimarypond.com/blog/5-effective-strategies-for-teaching-editing/

Alves, M. M. B. (2012). The Word Combination Card: A Writer’s Reference (2nd ed.). Language Arts Press.

Anderson, J. (2005). Mechanically Inclined: Building Grammar, Usage, and Style into Writer’s Workshop (Revised ed.). Stenhouse Publishers.

Carrier, K. A., & Tatum T. W. (2006). Creating Sentence Walls to help English Language Learners Develop Content Literacy. The Reading Teacher V. 6 No. 3, Nov. 2006.

Cooper, B., Kong, M. J., Bannister, M., & Tennen, D. (2020, January 8). How to Build Habits That Will Last All Year. Zapier. https://zapier.com/blog/effective-habit-change/

Foppoli, J. (2020, September 7). Is Grammar Really Important for a Second Language Learner? Eslbase. https://www.eslbase.com/teaching/grammar-important-second-language-learner

Gani, F. (2017, July 11). Top 10 Strategies for Learning New Skills. Zapier. https://zapier.com/blog/learning-new-skills/

Graff, G., Birkenstein, C., & Durst, R. K. (2012). “They Say/I Say.” W.W. Norton & Company.

Katie. (2018, February 14). How to practice a language like a pro. Joy Of Languages. http://joyoflanguages.com/how-to-practice-a-language/

Khazan, O. (2016, February 28). Why We Often Repeat the Same Mistakes. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/02/why-mistakes-are-often-repeated/470778/

Ovadia, J. (2019, November 27). Review of Teaching Grammar: A Sentence Composing Approach. MiddleWeb. https://www.middleweb.com/10550/grammar-writing/

Pennington, M. (2019, March 24). Why Daily Oral Language (D.O.L.) Doesn’t Work. Pennington Publishing Blog. https://blog.penningtonpublishing.com/grammar_mechanics/why-daily-oral-language-d-o-l-doesnt-work/comment-page-1/

Reyes, J. P., Jr. (2015, August 15). The Impact of Sentence Frames on Readers Workshop Responses. Education Commons. https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1176&context=hse_all

Stockton, N. (2018, July 19). What’s Up With That: Why It’s So Hard to Catch Your Own Typos. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2014/08/wuwt-typos/

Szynalski, T. P. (2011, November). Is “Pause and think” worth it? The Antimoon Blog. http://www.antimoon.com/blog/2011/11/is-pause-and-think-worth-it/

Taylor, E. (2017, October 29). Using Mentor Texts to Teach Writing! TeachWriting.Org. https://www.teachwriting.org/612th/2017/10/29/the-first-step-in-the-writing-process-is-reading-using-mentor-texts-to-teach-writing

Tran, T. H. (2013). Approaches to Treating Student Written Errors. Eric. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED545655.pdf

Witt, D., Soet, M. (2020, July 13). 5 Effective Modeling Strategies for English Learners. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/5-effective-modeling-strategies-english-learners

ELs Require Tier 2 Vocabulary Instruction to Unlock Content Area Learning

By Mary K. Mansfield

How often do English Learners (ELs) communicate effectively with friends but struggle in grade-level classrooms? How many frustrated classroom teachers ask ESL/Bilingual teachers, “I know Maria knows English, so why is she not doing her homework and failing my class?” The answer to both questions is ELs are still mastering academic language and are not able to perform as well as grade-level peers. The biggest challenge ELs face is trying to acquire academic English and learn academic curriculum simultaneously. ELs are successful when ESL/Bilingual and content area teachers support learners through Tier 2 vocabulary development. Tier 2 academic vocabulary instruction is a key to unlocking grade-level text; this article provides simple strategies to infuse vocabulary instruction into ESL and mainstream classrooms. There are ten easy-to-implement techniques that give classroom teachers ideas for ensuring Tier 2 vocabulary instruction is available for ELs. When all educators support teaching Tier 2 vocabulary in content areas, ELs master the curriculum. This collaborative approach is part of the WIDA 2020 Framework Standards which will be implemented in New Jersey in 2023.

ELs Struggle with Academic Vocabulary

When there is cooperation between teachers providing targeted focus teaching academic language, performance measures show an increase in student language acquisition. WIDA’s English Language Development Standards Framework, 2020 Edition is a resource for classroom educators to enhance the work being done in schools to ensure ELs receive needed content and language learning. In a February 2022 WIDA News article, Montecillo Leider details how she uses the WIDA’s English Language Development Standards Framework, 2020 Edition working with pre-service teachers to prepare them for working with ELs. Having effective tools and resources allows teachers to focus on language needed to support ELs in classrooms.

Challenges to Learning Academic Vocabulary

Learning English and grade-level content at the same time is demanding. Without the same English foundation as their grade-level peers, upper level elementary ELs can struggle when their English reading abilities are not at “grade level”. Fourth-graders are reading to gain knowledge, unlike kindergarten through third-grade students who are learning to read (Friesen & Haigh, 2018). Younger ELs learn vocabulary skills and strategies along with peers. By the upper elementary grades reading support diminishes, and reading demands increase. Additionally, it is more demanding to acquire academic English vocabulary (or L2) when ELs do not have a foundation in their first language (L1) (Friesen & Haigh, 2018). It is challenging to acquire English without a firm basis of morphology and syntax in students’ L1.

Helping ELs Build Academic Vocabulary

Students with a larger academic vocabulary repository perform better in school. Research shows that ELs with greater academic vocabulary score higher reading achievement (Ford, Cabell, Konold, Invernizzi, & Gartland, 2012). When ELs do not have the language to participate in class interactions, understand text, or write at the same level as their peers, they miss valuable learning interactions. Some educators view ELs with a large repertoire of social language capable of learning at the same rate as native speakers, however without understanding how to incorporate academic language they cannot. How can teachers help students learn to acquire the vocabulary needed to learn with grade-level peers? One answer is to focus teaching on Tier 2 vocabulary words. Beck, McKeown, and Kucan developed the Three Tier Model that categorizes vocabulary into three groups (1) Tier 1 words are basic vocabulary words, (2) Tier 2 words are general academic and multiple-meaning words, and (3) Tier 3 words are area-specific content words (Sibold, 2011 p. 24). Learning Tier 2 words unlocks text for ELs. Words such as analysis, comparison, hypothesis, and produce help students comprehend text, contribute to class discussions, and perform well on written assignments and exams. Words such as left, park, and swing, easily confuse ELs because they are unaware of multiple meanings (Sibold, 2011). Tier 2 vocabulary is not always found in everyday conversations, so students only interact with them in a text (Linden, 2013). Acquiring Tier 2 vocabulary allows ELs to unlock learning in classrooms.

Teaching Academic Vocabulary

ELs learn academic vocabulary in classrooms through discussion and reading but providing explicit instruction gives students tools to be future independent learners. Acquiring Tier 2 words increases text understanding, appears in texts across content areas, and often belongs to word families (Linden, 2013). Sharing these instruction strategies with content and mainstream teachers provides ELs with the support they need in all their classrooms. Sibold (2011) recommends direct vocabulary instruction beginning with the students receiving new Tier 2 vocabulary. Then ELs read, pronounce and highlight words in the text. The lessons then focus on determining word meanings guided by teachers with before, during, and after reading activities. Learning words in context helps students build strategies to further their vocabulary development on their own in the future. To solidify their understanding, students connect the word to something already known, such as L1 vocabulary (Sibold, 2011). Attaching words to something familiar builds better understanding. Christ and Wang (2010, p. 86) provide four suggestions for vocabulary instruction.

- Target vocabulary exposure through thematic units providing students experience words in multiple subject areas.

- Provide explicit vocabulary teaching before, during, and after reading instruction, ensuring students understand underlying word meanings.

- Teach vocabulary through modeling, guided practice, and independent practice.

- Supply multiple vocabulary exposures through discussion, reading, and writing, guaranteeing students can use the words in different contexts.

Strategies for Classrooms

Sibold (2011) provides easy to implement strategies for direct classroom academic vocabulary instruction. The chart below provides selected strategies and suggests easy implementation ideas for classrooms.

(Sibold, 2011, p. 26-28)

Supporting ELs in Mainstream Classrooms

When mainstream and content classroom teachers do not understand the intricacies of second language acquisition, they become frustrated because ELs have trouble mastering content area curriculum. Teachers are not familiar with Cummins’ postulate that it takes approximately five to seven years to develop CALP (Ferlazzo, 2014). ELs need to acquire years of academic language prior to attaining the same level as their peers. Research shows combined content and vocabulary instruction benefit ELs (Cervetti & Hiebert, 2015). ELs’ academic language increases when all educators support ELs with vocabulary development. ESL/Bilingual teachers are not solely responsible for students’ language development, content and mainstream teachers as well as administrators should understand the benefits of directly teaching academic and content vocabulary.

Suggestions for Classroom Teachers

All students win when content and mainstream classroom educators assist in developing ELs’ language. Classroom teachers need to understand language and vocabulary development for ELs and how to help acquire the academic vocabulary for their specific content area (Lopez & Iribarren, 2014). The list below shares ten suggestions for classroom teachers to support ELs in their vocabulary development.

- Understand the stages of second language acquisition and how Tier 2 vocabulary impacts learning (Lopez & Iribarren, 2014). Although second language acquisition is similar to L1 acquisition, it is not the same. Knowledge of the stages helps understand student linguistic needs.

- Realize English language proficiency (ELP) levels impact student performance (Pereira & de Oliveira, 2015). Knowing where students are in their listening, speaking, reading, and writing journey assists in developing appropriate assignments and assessments for ELs.

- Display English language objectives in addition to content area objectives (Goldenberg, 2008). Providing language objectives in writing gives a visual reminder of goals for developing academic language and vocabulary.

- Support in adapting curriculum to ELP levels empowering ELs to meet content objectives (Pereira & de Oliveira, 2015). Adapting curriculum ensures ELs successfully master required learning, minimizes potential gaps, and builds a foundation for future success.

- Furnish content in L1 and English (Kaplan, 2019). Building on ELs’ L1 facilitates learning in L2. Additionally, students familiar with curriculum content have an easier time mastering new vocabulary.

- Preview words and text in L1 (Goldenberg, 2008). Using students’ L1 provides background knowledge, increasing comprehension.

- Supply printed copies of text with highlighted Tier 2 vocabulary (Goldenberg, 2008). Alternatively, ensure students know how to use computer tools to manipulate online text.

- Develop question and response sentence frames so that ELs are comfortable contributing to class discussions (Ferlazzo, 2014). Sentence frames provide a low anxiety tool to participate in partner, small group, or whole-class conversations.

- Grant ELs extra time to work with peers and teachers (Goldenberg, 2008). ELs need more time to process learning. Encouraging conversation and study with native-speaking peers further develops academic vocabulary.

- Provide opportunities for additional practice with vocabulary (Goldenberg, 2008). Repeated exposure to academic vocabulary in multiple circumstances assists acquisition.

Conclusion

English Learners may struggle to learn academic content and L2 but achieve success when receiving targeted Tier 2 vocabulary development. Student achievement gaps develop if they have not acquired the language used in the curriculum, discussion, and texts. When students encounter academic vocabulary they are unfamiliar with, content comprehension suffers. ESL/Bilingual and classroom teachers need to understand their vital role in assisting ELs to unlock academic vocabulary to support all content area learning and straightforward Tier 2 teaching strategies for ESL/Bilingual and classroom teachers enable academic vocabulary acquisition leading to student success.